Play Guide

2021–2022 SEASON

Inside

818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415

ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000

BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.447.8243 (toll-free)

guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, Artistic Director

The Tempest

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by JOE DOWLING

February 26 – April 16, 2022

Wurtele Thrust Stage

THE PLAY

Synopsis, Setting and Characters • 4

Scene by Scene • 5

Responses to The Tempest • 7

THE PLAYWRIGHT

William Shakespeare • 9

A Legacy That Continues To Inspire • 10

Shakespeare’s Plays • 12

CULTURAL CONTEXT

A Play With Manifold Sources • 13

A Farewell to Arts • 16

Selected Glossary of Terms • 18

EDUCATION RESOURCES

Discussion Questions and Activities • 19

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For Further Reading and Understanding • 22

Guthrie Theater Play Guide

Copyright 2022

PRODUCTION DRAMATURG Carla Steen

GRAPHIC DESIGNER Brian Bressler

EDITOR Johanna Buch

CONTRIBUTORS Vanessa Brooke Agnes,

Stephanie Anne Bertumen, Maija García,

Carla Steen

The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the

imagination, stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the

illumination of our common humanity.

All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this play guide may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the

publishers. Some materials are written especially for our guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers.

The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the

Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts Board received additional funds to support this activity from the National Endowment for the Arts.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Source Material • 13

THE PLAY

Synopsis • 4

THE PLAYWRIGHT

William Shakespeare • 9

2 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

This play guide is designed to fuel your curiosity and deepen your understanding of a show’s

history, meaning and cultural relevance so you can make the most of your theatergoing

experience. You might be reading this because you fell in love with a show you saw at the

Guthrie. Maybe you want to read up on a play before you see it onstage. Or perhaps you’re a

fellow theater company doing research for an upcoming production. We’re glad you found your

way here, and we encourage you to dig in and mine the depths of this extraordinary story.

NOTE: Sections of this play guide may evolve throughout the run of the show, so check back

often for additional content.

About This Guide

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Thanks for your interest in The Tempest. Please direct literary inquiries to Resident Dramaturg

Carla Steen at carlas@guthrietheater.org.

“The rarer action

is in virtue than

in vengeance.”

– Prospera in The Tempest (Act Five, Scene One)

3 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

THE PLAY

Synopsis

Twelve years before the play’s start, Prospera is usurped of her dukedom

of Milan by her brother, Antonio — with the aid of Alonso, the king of

Naples, and his brother, Sebastian — and banished to this island with her

then-3-year-old daughter, Miranda. Prospera has engaged in an intense

study of secret arts, which allows her to thrive on the island, whose only

other inhabitants are the elemental spirit Ariel and a witch’s son Caliban,

both of whom now serve Prospera.

The action of the play begins with Alonso, Antonio and others, including

Alonso’s son, Ferdinand, and an old councilor Gonzala, sailing near

the island. Prospera uses her art to conjure a tempest that strands

her enemies on her island. Under Ariel’s management, the perfectly

unharmed castaways are separated into three groups: Alonso, Antonio

and the rest of the royal court; Ferdinand, alone; and the butler

Stephano and jester Trinculo. The mariners remain onboard asleep.

Although Prospera wants revenge for being usurped, her main goal is to

bring together Ferdinand and Miranda in the hope they will fall in love.

Ferdinand, who thinks his father has died, does indeed fall in love with

Miranda and is immediately put through his paces by Prospera in order

to earn her as his wife, thus securing Miranda’s future.

Likewise, Alonso believes his son is dead, and Antonio suggests to

Sebastian, the king’s brother, that he should kill Alonso and take his

now heirless throne. The attempt is thwarted, but Prospera charges

Ariel to torment them for their past misdeeds. Elsewhere on the island,

Stephano and Trinculo have drunken interactions with Caliban, who

happily pledges allegiance to Stephano if the butler will kill Prospera.

Prospera devises to bring all the parties together at her cell, reuniting

Ferdinand and Alonso, confirming the marriage of Ferdinand and

Miranda, privately calling out Sebastian and Antonio, getting her

dukedom back, sidestepping Caliban’s murder plot and granting Ariel’s

long-promised freedom. After a night of rest, everyone plans to leave

the island for Naples. Prospera promises to break her sta and drown

her spell book, renouncing magic altogether.

In an epilogue, Prospera addresses the audience, asking for their

applause to release her from the island.

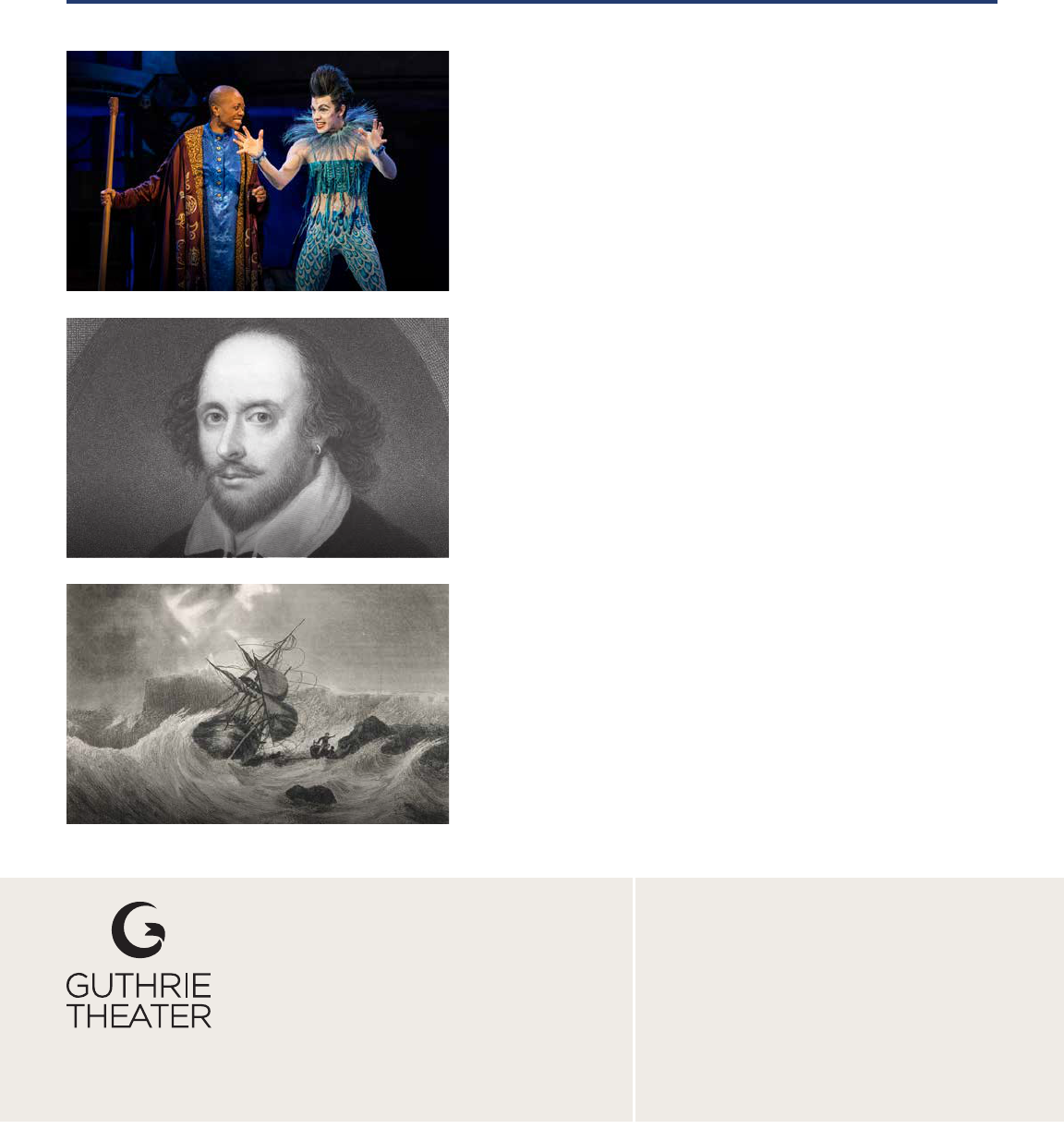

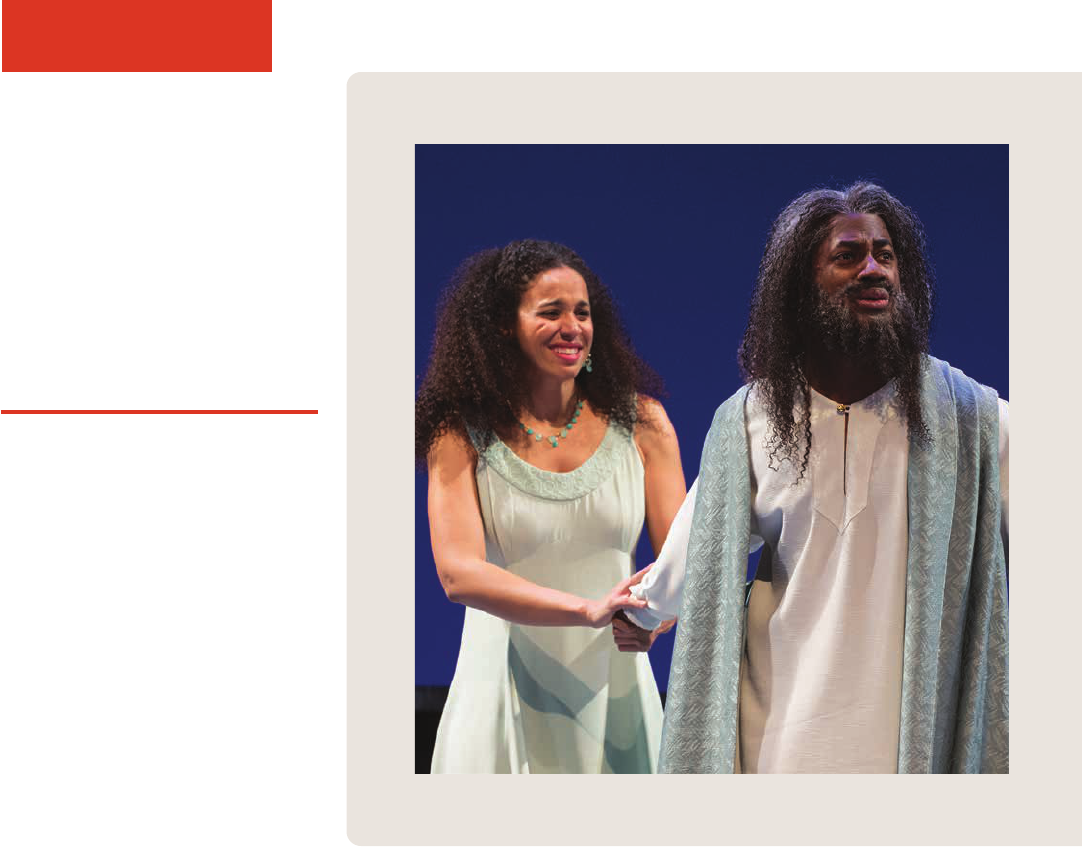

PHOTO: REGINA MARIE WILLIAMS AND TYLER MICHAELS KING (DAN NORMAN)

SETTING

On a yacht, then an

uninhabited island in the

Mediterranean Sea.

CHARACTERS

Prospera, rightful duke of Milan

Miranda, her daughter

Ariel, an airy spirit

Caliban, an enslaved man

Ceres, a goddess

Juno, a goddess

Iris, a goddess

Spirits and Hounds

Ariel’s Musician

Alonso, king of Naples

Ferdinand, his son

Sebastian, Alonso’s brother

Antonio, Prospera’s brother

Gonzala, a councilor

Adrian, a courtier

Francisca, a courtier

Stephano, Alonso’s butler

Trinculo, Alonso’s jester

Captain

Boatswain

Mariners

Spirits, Hounds

4 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

Scene by Scene

THE PLAY

ACT ONE

Scene One

On a ship, the Captain and Boatswain try to get

a ship (carrying Alonso, the king of Naples, and

his royal court) under control in the midst of a

raging storm.

Scene Two

On a nearby island, Miranda frets over the ship, but

her mother, Prospera, reassures her that no one

was injured and tells her the story of their exile to

this island. Prospera was deposed by her brother,

Antonio, when Miranda was a small child. The sprite

Ariel relates to Prospera how the storm played out

and where everyone on the ship is now. They note

the time and that Ariel’s freedom is soon to come.

Ariel has served Prospera since she freed him from a

tree in which the witch Sycorax had imprisoned him.

Syrcorax was the mother of the only other inhabitant

of the island, Caliban. Alonso’s son, Ferdinand, is led

in by Ariel and mourns his drowned father. Miranda

and Ferdinand are smitten with each other. To test

his devotion, Prospera charms Ferdinand and leads

him o to imprison him.

ACT TWO

Scene One

As councilor Gonzala tries to keep Alonso’s spirits up

(because he fears Ferdinand has drowned), Antonio

and Alonso’s brother, Sebastian, mock her. Gonzala

notes it’s odd that their clothes are as fresh as when

they left Tunis. Ariel puts everyone to sleep with music

except Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio, who encourage

the king to sleep while they keep watch. As Alonso

sleeps, they plot his assassination so Sebastian can

take the crown. Just as they plan to strike, Ariel wakes

the sleepers up, so the conspirators feign hearing an

animal. They all leave to keep looking for Ferdinand.

Scene Two

Caliban gathers wood for Prospera when he hides,

mistaking Trinculo (Alonso’s jester) for a spirit. Trinculo

wonders at Caliban but takes refuge from the storm

under Caliban’s cloak. Alonso’s butler Stephano comes

in singing and sees a four-legged creature (Trinculo

and Caliban under the same cloak). Stephano shares

his wine with Caliban and is reunited with Trinculo.

Caliban is impressed by Stephano — and the alcohol —

and takes him for a god and promises to serve him.

IMAGE: SET DESIGN BY ALEXANDER DODGE

5 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

ACT THREE

Scene One

Ferdinand hauls wood until Miranda takes over for him

so he can rest. They talk, reveal they’re in love with

each other and agree to marry. Prospera, observing

from afar, is satisfied.

Scene Two

Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban are drunk. Ariel enters

and mimics Trinculo’s voice, making the others mad at

him for contradicting them. Caliban pleads his case to

Stephano, saying that Prospera’s nap is a good time

to kill her, take over the island and claim Miranda as

queen. Ariel plays music and they follow it.

Scene Three

The king’s group is still wandering the island, with

Sebastian and Antonio planning to strike that night

when everyone is exhausted. Shapes bring in a

banquet, and they debate whether it’s safe to eat. Ariel,

disguised as a Harpy, takes it away just as they decide

to eat and accuses the three of wronging Prospera.

Alonso, Antonio and Sebastian run away aghast.

ACT FOUR

Scene One

Ferdinand and Miranda are betrothed, but they must

wait until a full ceremony to act on their passion,

upon pain of a curse. Ariel reports on the others, and

Prospera tells him to bring them all to her. Meanwhile,

Prospera blesses Miranda and Ferdinand with an

entertainment by Iris, Juno and Ceres, plus nymphs

and reapers. The shapes disappear when Prospera

remembers Caliban’s conspiracy and tells Ariel to get

clothes to attract the three others to her cell — a plan

that succeeds, and Trinculo and Stephano put on the

clothes. Caliban frets that they are missing their window

to act against Prospera. Spirits as hounds chase them

o while Prospera attends to other business.

ACT FIVE

Scene One

The time has come for Prospera’s plan to be fulfilled.

Ariel says he has sympathy for the king and the rest of

his party, and Prospera says perhaps she should, too,

and gives up her quest for revenge. Prospera draws

a circle, renounces magic and Ariel brings in Alonso

and his party, still foggy from the charms. Prospera

changes into her ducal robes, sends Ariel to fetch the

Captain and Boatswain and then presents herself to

Alonso’s group, who finally recognize her and have

many questions about how she arrived on the island.

Alonso restores her dukedom, and Prospera tells

Sebastian and Antonio she knows they’re traitors but

will keep the secret for now. She sympathizes with

Alonso’s loss of a child before revealing Ferdinand and

Miranda playing chess. There is much happiness in the

reunion, and Miranda is overawed at so many people.

Their marriage is revealed and approved by Alonso.

The Captain and Boatswain report that the ship is

undamaged and are amazed that everyone is alive.

Caliban, Trinculo and Stephano come in drunk and

stinky. Caliban is sent to Prospera’s house to prepare it

for guests while Prospera promises to tell her full story

and provide calm seas so the king’s ship can catch

up with the rest of the fleet. She intends to return to

Milan. Ariel is free.

Epilogue

Prospera asks the audience to help return her to Naples

and release her from the island — and theater — via

their applause.

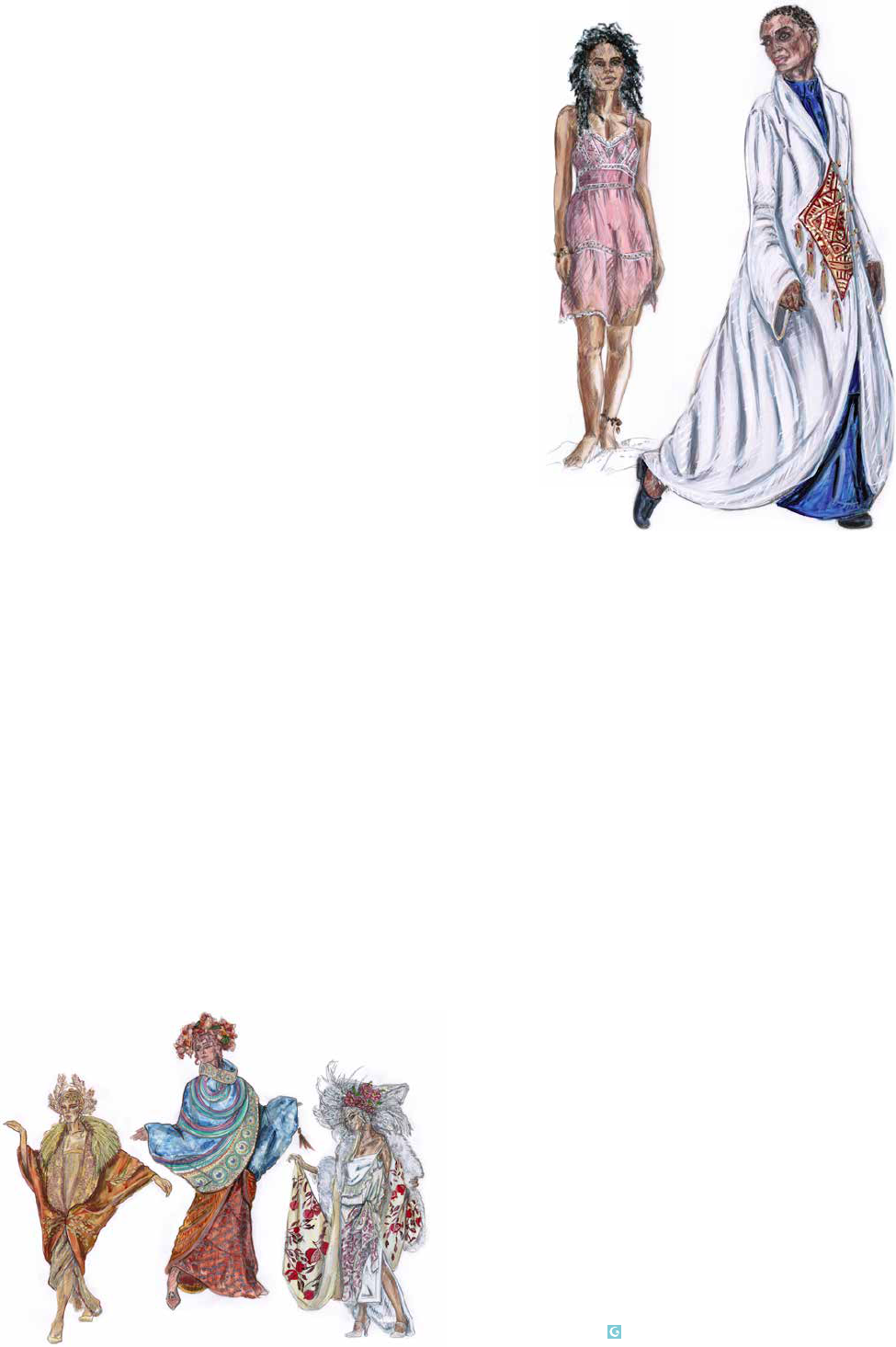

IMAGES: COSTUME DESIGN BY ANN HOULD-WARD

Ceres, Iris and Juno

Miranda and

Prospera

6 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

Responses to The Tempest

THE PLAY

EDITOR’S NOTE: The comments below refer to Prospero (he/him), as the character was written by Shakespeare

to be male. This Guthrie production has changed the genders of Prospero, Gonzalo and Francisco to be female

characters named Prospera, Gonzala and Francisca.

Critics have frequently identified Prospero’s art as

theurgy [control over supernatural power] and often

related it to neoplatonic theories of magic. The

intellectual quality of his magic, his command over

Ariel (who is clearly daemon, not demon), his concern

for astrological guidance, and his use of music in his

magic have all been cited to prove his theurgistic and

neoplatonic associations. …

The magical contest between Prospero and Sycorax

is presented with great care, even though it is

narrated by Prospero and Ariel and not witnessed

by the audience. … In The Tempest, as in most plays

involving magical competition, the triumph of a given

side proves its moral superiority to the magic of the

loser, thereby justifying the winner’s magic. After all,

only Prospero’s more powerful “good” magic can

counteract the “bad” magic of Sycorax. Shakespeare

clearly included this account of Prospero’s indirect

competition with Sycorax to strengthen Prospero’s

credentials as a “good” magician. …

Shakespeare carefully depicted the relationship

between Ariel and Prospero. Prospero never conjures

or ritually summons Ariel onstage; all his bonds of

control over the spirit were forged before the play

began; onstage a simple command brings Ariel to

serve his magician (occasionally with some protest).

… A beautifully particularized representative of a long

line of spirits who serve magicians, Ariel provides

spectacle, proof of Prospero’s power, and helps

explain how the play’s magic is performed. Prospero

alone is not capable, if he is human, of raising a

tempest or of making unearthly music. Only by gaining

control of the spirits who manage the functioning

of the natural world can a man accomplish what

Prospero does; Ariel is a necessary intermediary. As

such, he leaves Prospero’s humanity intact.

Barbara Howard Traister

“Prospero: Master of Self-Knowledge,” Heavenly Necromancers:

The Magician in English Renaissance Drama, 1984

[T]he nature of the magic in The Tempest has received a good

deal of critical attention and persuasive explication.

The Tempest is a mirror in which, if we hold it very still, we can gaze backward at all of

[Shakespeare’s] recent plays; and behind them will be glimpses of a past as old as the tragedies,

the middle comedies and even A Midsummer Night's Dream. ... The play seems to order itself in

terms of its meanings; things in it stand for other things, so that we are tempted to search its

dark backward for a single meaning, quite final for Shakespeare and quite abstract. The trouble

is that the meanings are not self-evident. One interpretation of The Tempest does not agree

with another. And there is deeper trouble in the truth that any interpretation, even the wildest, is

more or less plausible. This deep trouble, and this deep truth, should warn us that The Tempest

is a composition about which we had better not be too knowing.

Mark Van Doren

Shakespeare, 1939

7 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

Shakespeare’s plays are still worth our attention

because they body forth so brilliantly the virulent

and interesting disease called Western culture.

Racism, imperial domination, anti-Semitism, sexist

craziness and the phallic code of war are not

incidental to that culture. They have been intrinsic

parts of it, and Shakespeare gives us a wonderful

map of the metaphorical system by which that

culture enforces itself. ...

I don’t mean to argue for a Shakespeare who was

a feminist, or a Marxist. Shakespeare was obviously

interested in order, hierarchy and patriarchy. But he

was also a connoisseur of disorder, civil war, family

strife, madness and rebellion. The spark of dramatic

interest always lies in his perception of flaws,

tensions and anomalies in the dominant ideology. He

exploits these cracks, expressing problems covered

over by the apparent social consensus.

Charles Sugnet

“Shakespeare Without Guts,” In Our Times, December 23, 1981 –

January 12, 1982

The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and

The Merry Wives of Windsor, which was written

for a command performance, are the only plays of

Shakespeare with an original pot. The Tempest is

also his only play observing the unities of time, place,

and action — which accounts for Prospero’s long,

expository narrative at the beginning of the play

instead of action. …

The Tempest ends, like the other plays in

Shakespeare’s last period, in reconciliation and

forgiveness. But the ending in The Tempest is grimmer,

and the sky is darker than in The Winter’s Tale,

Pericles and Cymbeline. Everybody in the earlier plays

asks forgiveness and gets it, but Prospero, Miranda,

Ferdinand, Gonzalo and Alonso are the only ones

really in the magic circle of The Tempest. Alonso is

forgiven because he asks to be. He is the least guilty,

and he suers most. … Neither Antonio nor Sebastian

say a word to Prospero — their only words after the

reconciliation are mockery at Trinculo, Stephano and

Caliban. They’re spared punishment, but they can’t

be said to be forgiven because they don’t want to

be, and Prospero’s forgiveness of them means only

that he does not take revenge upon them. Caliban is

pardoned conditionally, and he, Stephano and Trinculo

can’t be said to be repentant. They realize only that

they’re on the wrong side, and admit they are fools,

not that they are wrong.

W. H. Auden

Lectures on Shakespeare, 2000

These readings very much depend on one’s

conception of European man’s place in

the universe, and on whether a figure like

Prospero stands for all mankind or for one

side of a conflict.

The first interpretation, following upon the

ideas of Renaissance humanism and the

place of the artist/playwright/magician,

oers a story of mankind at the center

of the universe, of “man” as creator and

authority. … Prospero has often been seen

as a figure for the artist as creator — as

Shakespeare’s stand-in, so to speak, or

Shakespeare’s self-conception, an artist

figure unifying the world around him by his

“so potent art.” … Prospero’s magic books

enable him as well to thwart the incipient

revolts of both high and low conspirators,

and to exact a species of revenge against

those who usurped his dukedom and set

him adrift on the sea — for The Tempest

is one of Shakespeare’s most compelling

“revenge tragedies,” turned, at the last

moment, toward forgiveness. …

The second kind of interpretation, the

colonial or postcolonial narrative, follows

upon early modern voyages of exploration

and discovery, “first contact,” and the

encounters with, and exploitation of,

indigenous peoples in the New World. In

this interpretive context The Tempest is not

idealizing, aesthetic, and “timeless,” but

rather topical, contextual, “political,” and in

dialogue with the times. Yet manifestly this

dichotomy will break down, both in literary

analysis and in performance. It is perfectly

possible for a play about a mage, artist, and

father to be, at the same time, a play about

a colonial governor, since Prospero himself

is, or was, the Duke of Milan.

Marjorie Garber

Shakespeare After All, 2008

Shakespeare’s powerful late

romance The Tempest has been

addressed by modern critics from

two important perspectives: as a

fable of art and creation, and as a

colonialist allegory.

8 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

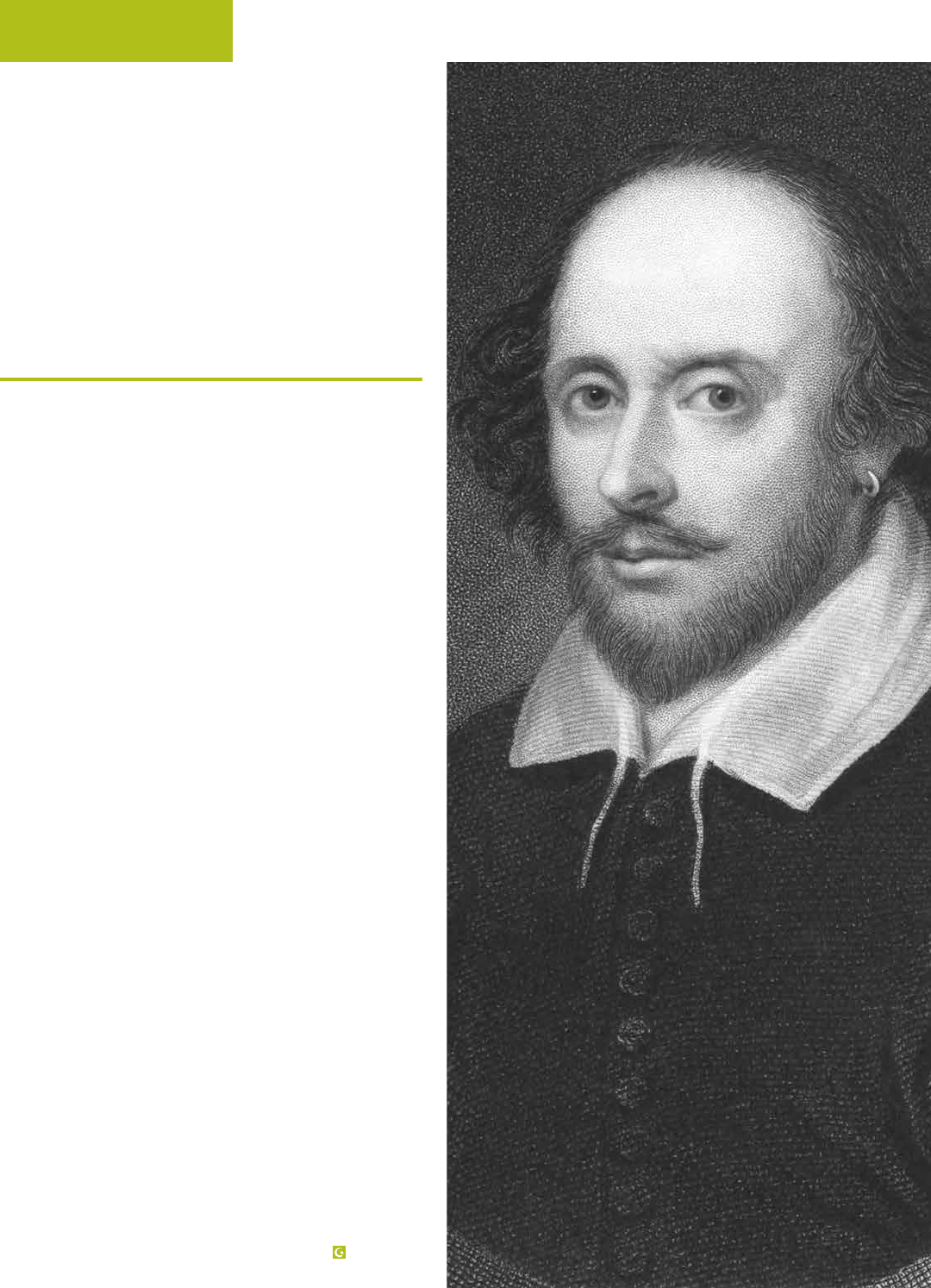

PLAY FEATURETHE PLAYWRIGHT

William

Shakespeare

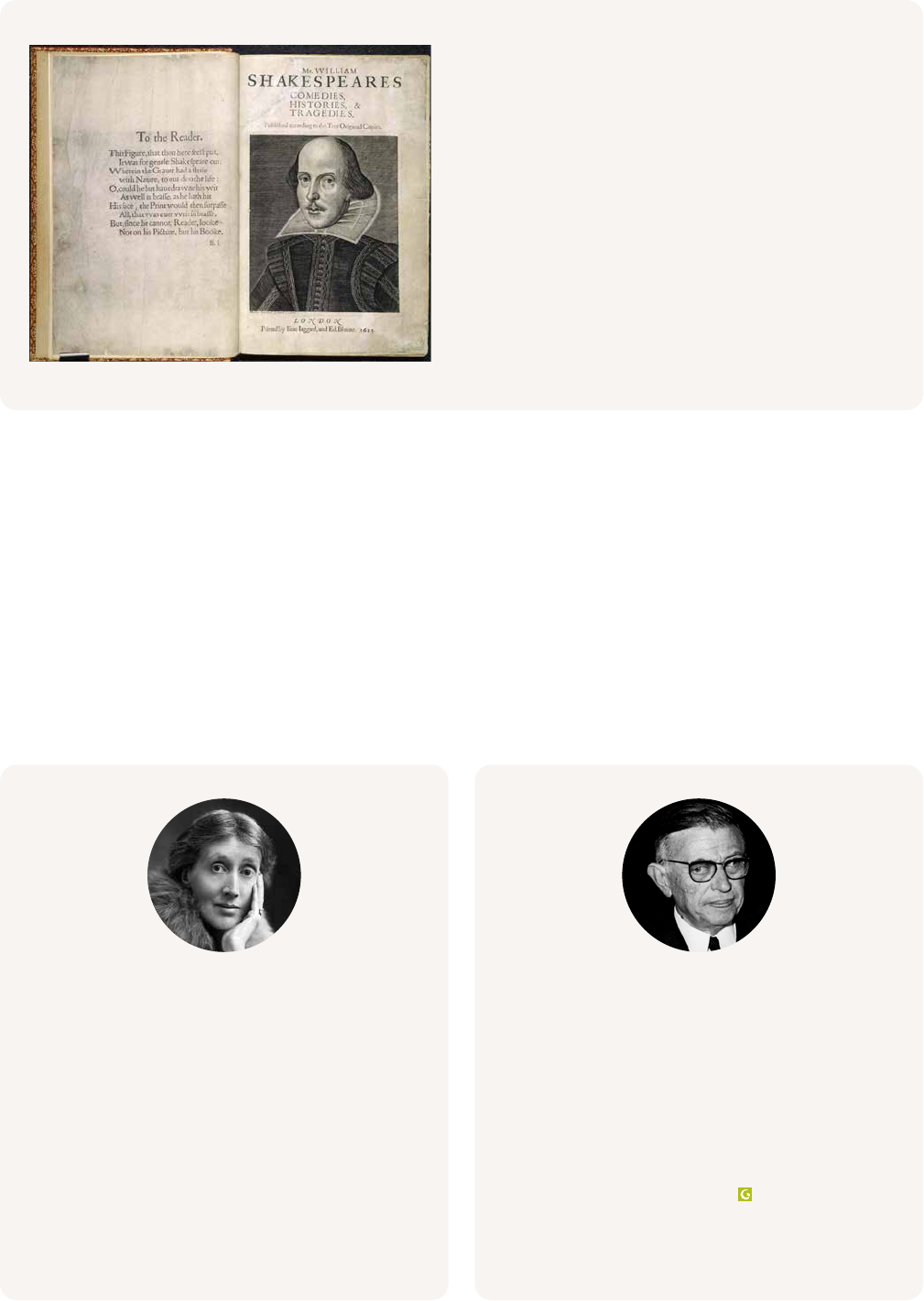

William Shakespeare was born in 1564 to John

and Mary Arden Shakespeare and raised in

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, in England’s

West Country.

Much of the information about him comes from

ocial documents such as wills, legal documents

and court records. There are also contemporary

references to him and his writing. While much of the

biographical information is sketchy and incomplete,

for a person of his class and as the son of a town

alderman, quite a lot of information is available.

Young Shakespeare would have attended the

Stratford grammar school, where he would have

learned to read and write not only English, but

also Latin and some Greek. In 1582, at age 18,

Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, and the

couple had three children: Susanna in 1583 and

twins Hamnet and Judith in 1585.

After an eight-year gap where Shakespeare’s

activity is not known, he appeared in London by

1592 and quickly began to make a name for himself

as a prolific playwright. He stayed in London for

about 20 years, becoming increasingly successful

in his work as an actor, writer and shareholder in

his acting company. Retirement took him back to

Stratford to lead the life of a country gentleman.

His son Hamnet died at age 11, but both daughters

were married: Susanna to Dr. John Hall and Judith

to Thomas Quiney.

Shakespeare died in Stratford in 1616 on April 23,

which is thought to be his birthday. He is buried in

the parish church, where his grave can be seen to

this day. His known body of work includes at least

37 plays, two long poems and 154 sonnets.

9 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

PLAY FEATURETHE PLAYWRIGHT

A Legacy That

Continues To Inspire

The Poetry of Shakespeare was

Inspiration indeed: he is not so

much an Imitator as an Instrument

of Nature; and ’tis not so just to

say that he speaks from her, as

that she speaks through him.

Alexander Pope

Preface to The Works of Shakespeare, 1725

We do not understand Shakespeare

from a single reading, and certainly

not from a single play. There is a

relation between the various plays of

Shakespeare, taken in order; and it

is work of years to venture even one

individual interpretation of the pattern

in Shakespeare’s carpet.

T.S. Eliot

“Dante,” Selected Essays, Faber & Faber, 1929

If one takes those thirty-seven plays with all the radar lines of the dierent viewpoints

of the dierent characters, one comes out with a field of incredible density and

complexity; and eventually one goes a step further, and one finds that what happened,

what passed through this man called Shakespeare and came into existence on

sheets of paper, is something quite dierent from any other author’s work. It’s not

Shakespeare’s view of the world, it’s something which actually resembles reality. A sign

of this is that any single word, line, character or event has not only a large number of

interpretations, but an unlimited number. Which is the characteristic of reality. … An

artist may try to capture and reflect your action, but actually he interprets it — so that

a naturalistic painting, a Picasso painting, a photograph, are all interpretations. But in

itself, the action of one man touching his head is open to unlimited understanding and

interpretation. In reality, that is. What Shakespeare wrote carries that characteristic.

What he wrote is not interpretations: it is the thing itself.

Peter Brook

“What is Shakespeare?” (1947), in The Shifting Point, Harper & Row, 1987

10 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

[A]lthough each play is a separate and individual

work of art, they all generally illuminate one

another, and taken together they form an

impressive achievement in which each individual

play acquires more weight and dignity when

placed against the background of the whole

corpus. Each play is more or less a landmark

in the road along which Shakespeare the artist

traveled, or, to change the metaphor, each play is

a variation on a number of themes that recur in

the poet’s work.

M.M. Badawn

Background to Shakespeare, Macmillian India Limited, 1981

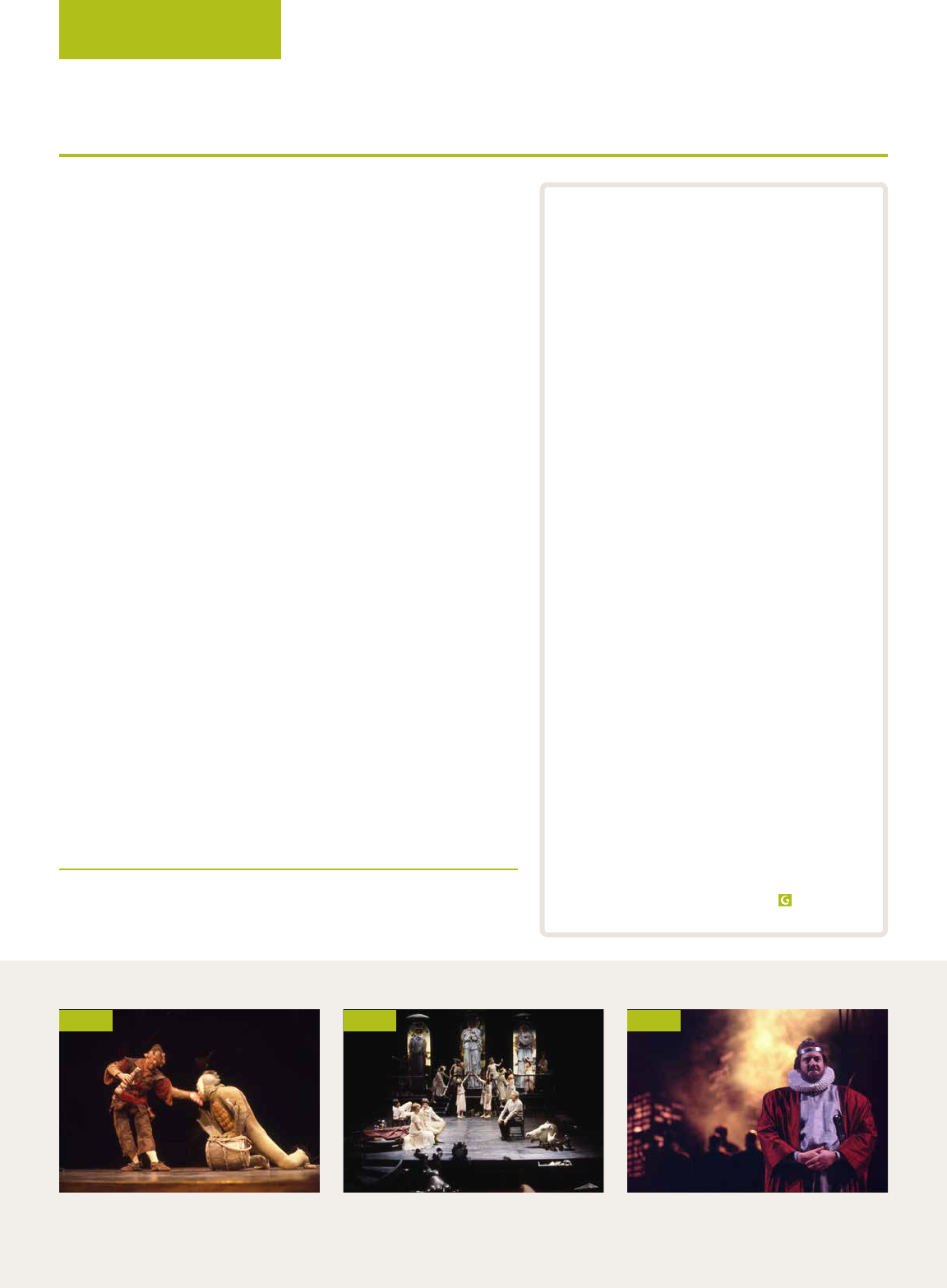

Shakespeare’s mind is the type

of the androgynous, of the man-

woman mind. … It is fatal for

anyone who writes to think of their

sex. It is fatal to be a man or a

woman pure and simple; one must

be woman-manly or man-womanly.

Virginia Woolf

A Room of One’s Own, 1929

His characters are intimately bound

up with the audience. That is why

his plays are the greatest example

there is of a people’s theater; in

this theater the public found and

still finds its own problems and

re-experiences them.

Jean-Paul Sartre

On Theater, 1959

Every age creates its own Shakespeare. … Like a portrait whose

eyes seem to follow you around the room, engaging your glance

from every angle, [his] plays and their characters seem always

to be “modern,” always to be “us.”

Marjorie Garber

Shakespeare After All, Anchor Books, 2004

11 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

PLAY FEATURETHE PLAYWRIGHT

Shakespeare’s Plays

EARLY PERIOD

ca – The Two Gentlemen of Verona

ca – Titus Andronicus

ca Henry IV, Part II

ca – Henry IV, Part III

ca The Taming of the Shrew

ca Henry IV, Part I Richard III

ca The Comedy of Errors Love’s Labour’s Lost

MIDDLE PERIOD

ca Richard II Romeo and Juliet

ca A Midsummer Night’s Dream King John

The Merchant of Venice

ca Henry IV, Part I Henry IV, Part II

Much Ado About Nothing

ca Henry V Julius Caesar

ca As You Like It The Merry Wives of Windsor

ca Twelfth Night

ca Troilus and Cressida

ca – Hamlet

ca Othello Measure for Measure

ca – All’s Well That Ends Well King Lear Macbeth

LATE PERIOD

ca Timon of Athens Antony and Cleopatra

ca Pericles Coriolanus

ca – The Winter’s Tale

ca Cymbeline

ca The Tempest

ca Henry VIII

ca – The Two Noble Kinsmen

Authorship and dating of Shakespeare’s plays is a subject of much academic

debate. These dates are speculative, but are the “most probable” dating from

The New Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works.

THE TEMPEST

The Tempest was written around 1611

and may have premiered by the end

of that year at the Palace of Whitehall

before James I. Public performances

were given at the indoor Blackfriars

Theatre. Along with Pericles, Cymbeline

and The Winter’s Tale, it is one of

Shakespeare’s late plays, sometimes

called romances, which mix elements of

tragedy and comedy. While The Tempest

isn’t his absolutely final play, it’s late

enough in his body of work that many

people have often considered it to be

Shakespeare’s farewell to the stage.

The Tempest stands out in the

Shakespeare canon for a number of

reasons. Its action occurs over the

course of a few hours and in one

location, making it one of the few

plays by Shakespeare that align with

the classical unities of time, place

and action. The plot is mostly original

to Shakespeare and may have been

inspired by contemporary shipwrecks

among early colonial expeditions to

the Americas and Africa. Prospera — a

puppet master extraordinaire — is one

of the great roles in all of the Bard’s

plays, while Ariel and Caliban provide

depth and richness in their loyalty and

resentment toward Prospera.

THE GUTHRIE HAS PREVIOUSLY PRODUCED THE TEMPEST THREE TIMES:

Directed by Philip Minor Directed by Liviu Ciulei Directed by Jennifer Tipton

PHOTO: RICHARD S. IGLEWSKI (MICHAL DANIEL)PHOTO: BRUCE GOLDSTEINPHOTO: PAUL BALLANTYNE AND CHARLES KEATING (FILE PHOTO)

12 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

PLAY FEATURECULTURAL CONTEXT

A Play With Manifold Sources

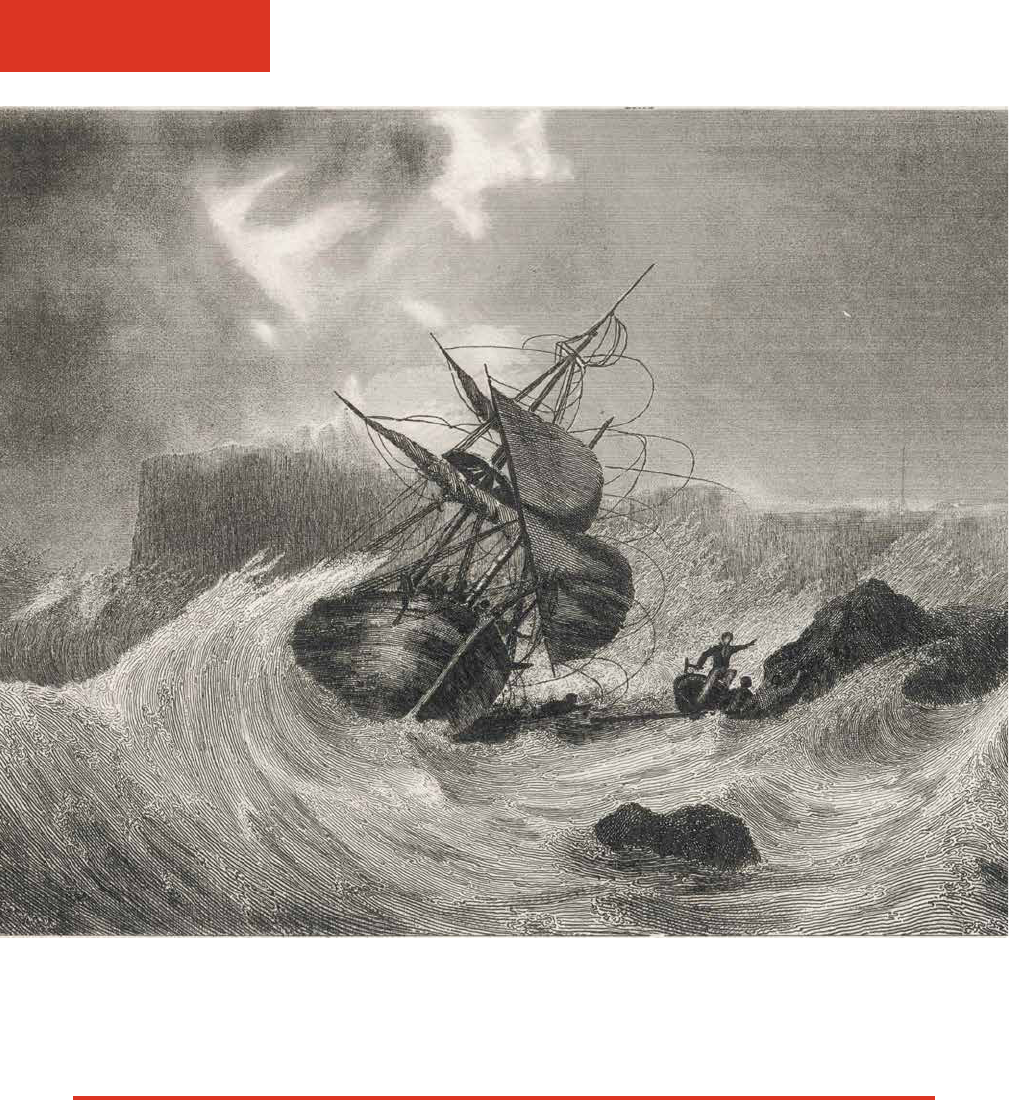

While the plot of The Tempest is mostly original to Shakespeare, he drew on

several influences both old and contemporary to create his tale. There were

scenarios circulating in Italian commedia dell’arte with storylines very much

like that of The Tempest, and European exploration of the Americas led to

inevitable notable shipwrecks.

In 1609, nine ships headed to Jamestown, Virginia, were caught in a storm near Bermuda, during

which the flagship got separated and was assumed lost. But the people on board made it ashore

in the Bermudas, built two small boats and showed up in Jamestown a year later. Among the

other ideas that fueled the creation of The Tempest were a speech in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, an

essay by Montaigne and courtly entertainments called masques.

13 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

OVID’S METAMORPHOSES

Prospera’s Act Five speech, in which she renounces magic, is often considered an almost direct borrowing by

Shakespeare from a speech delivered by Medea in Ovid’s story about her marriage to the hero Jason in a 1567

translation by Arthur Golding. For comparison, we placed the speeches side by side and noted the similarities.

NOTE: Before this speech, Jason has arrived in Medea’s homeland of Colchis to collect the Golden Fleece.

Medea’s father, the king, sets up feats for Jason to accomplish and, with her magic, Medea — passionately in love

with Jason — helps Jason successfully complete them and get the Fleece. When they return to Jason’s land of

Iolchus, he asks Medea to take years from his life and give them to his aged father, Aeson. Medea says she can’t

do that, but she’ll ask Hecate for aid in extending Aeson’s life.

MEDEA

Upon the bare, hard ground she said, “O trusty time of night

Most faithful unto privities, O golden stars whose light

Doth jointly with the moon succeed the beams that blaze

by day,

And thou three-headed Hecate, who knowest best the way

To compass this our great attempt and art our chiefest stay;

Ye Charms and Witchcrafts, and thou Earth, which both with

herb and weed

Of mighty working furnishest the Wizards at their need;

Ye Airs and winds; ye Elves of Hills, of Brooks, of Woods alone,

Of standing Lakes, and of the Night, approach ye every one,

Through help of whom (the crooked banks much wond’ring

at the thing)

I have compelled streams to run clean backward to their

spring.

By charms I make the calm seas rough and make the rough

seas plain,

And cover all the sky with clouds and chase them thence

again.

By charms I raise and lay the winds and burst the Viper’s jaw,

And from the bowels of the earth both stones and trees do

draw.

Whole woods and Forests I remove; I make the Mountains

shake,

And even the Earth itself to groan and fearfully to quake.

I call up dead men from their graves; and thee, O lightsome

Moon,

I darken oft, though beaten brass abate thy peril soon;

Our Sorcery dims the Morning fair and darks the Sun at Noon.

...

Now have I need of herbs that can by virtue of their juice

To flowering prime of lusty youth old withered age reduce.

I am assured ye will it grant; for not in vain have shone

These twinkling stars, ne yet in vain this chariot all alone

By draught of dragons hither comes.” With that was from

the sky

A chariot softly glanced down, and stayed hard thereby.

PROSPERA

You elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes,

and groves,

And you that on the sands with printless foot

Do chase the ebbing Neptune, and do fly him

When he comes back; you demi-puppets that

By moonshine do the green sour ringlets

make,

Whereof the ewe not bites; and you whose

pastime

Is to make midnight mushrumps, that rejoice

To hear the solemn curfew; by whose aid,

Weak masters though you be, I have

bedimmed

The noontide sun, called forth the mutinous

winds,

And ’twixt the green sea and the azured vault

Set roaring war; to the dread rattling thunder

Have I given fire, and rifted Jove’s stout oak

With his own bolt; the strong-based

promontory

Have I made shake, and by the spurs plucked

up

The pine and cedar; graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ’em

forth

By my so potent art. But this rough magic

I here abjure, and when I have required

Some heavenly music, which even now I do,

To work mine end upon their senses that

This airy charm is for, I’ll break my sta,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

METAMORPHOSES THE TEMPEST

14 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

COURT MASQUES

A specific entertainment that hit its zenith in England during the Stuart monarchies, the court masque is the

basis for the “vanity of mine art” that Prospera creates to celebrate the engagement of Miranda to Ferdinand in

Act Four. Prospera instructs Ariel to bring other spirits, who then take the form of the goddesses Iris, Juno and

Ceres to bless the couple. The spectacle ends in a lively dance complete with nymphs and reapers. (The Tempest

was performed at court to honor the marriage of James I’s daughter Elizabeth during the winter of 1611–1612.)

The masque could encompass many forms — theater, pageants or processions. No matter the form or style,

what bound them together was the celebration and glorification of the monarch or a member of the nobility.

The Tudors (James I and Charles I) tended to favor theatrical masques, which could include music and three

dances, with the dancers often being members of the court. Professional musicians and actors also performed in

masques, which led to the introduction of masque-like elements into theater troupes’ non-court work. Featuring

mythological, classical or even allegorical characters, masques almost always put spectacle at the center, resulting

in enormously expensive productions with elaborate scenic elements. In 1618, James I spent more on one masque

than he had spent collectively on all professional theater troupes’ plays during the whole of his reign.

MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE’S “OF CANNIBALS” ESSAY

In her Act Two speech, Gonzala describes an image of a Golden Age, often thought in classical mythology as the

first age of the world and in biblical terms as a Garden of Eden. The Golden Age was followed by “progressively

degenerate” ages of Silver, Bronze and Lead. The idea of (or returning to) a Golden Age captured minds in dierent

periods, and at the time of Shakespeare’s writing, Native Americans were often seen by Europeans as innocents of

a Golden Age. Gonzala’s ideas align with parts of Montaigne’s “Of Cannibals,” an essay available to Shakespeare via

John Florio’s 1603 translation. For comparison, we placed the texts side by side and noted the similarities.

MONTAIGNE

These nations then seem to me to be so far barbarous, as

having received but very little form and fashion from art and

human invention, and consequently to be not much remote

from their original simplicity. The laws of nature, however,

govern them still, not as yet much vitiated with any mixture of

ours: but ‘tis in such purity, that I am sometimes troubled we

were not sooner acquainted with these people, and that they

were not discovered in those better times, when there were

men much more able to judge of them than we are. I am sorry

that Lycurgus and Plato had no knowledge of them; for to my

apprehension, what we now see in those nations, does not only

surpass all the pictures with which the poets have adorned the

golden age, and all their inventions in feigning a happy state

of man, but, moreover, the fancy and even the wish and desire

of philosophy itself; so native and so pure a simplicity, as we

by experience see to be in them, could never enter into their

imagination, nor could they ever believe that human society

could have been maintained with so little artifice and human

patchwork. I should tell Plato that it is a nation wherein there

is no manner of trac, no knowledge of letters, no science of

numbers, no name of magistrate or political superiority; no

use of service, riches or poverty, no contracts, no successions,

no dividends, no properties, no employments, but those of

leisure, no respect of kindred, but common, no clothing, no

agriculture, no metal, no use of corn or wine; the very words

that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy,

detraction, pardon, never heard of.

GONZALA

Had I plantation of this isle, my lord —

— And were the king on’t, what would I do?

I’th’commonwealth I would by contraries

Execute all things, for no kind of trac

Would I admit; no name of magistrate;

Letters should not be known; riches, poverty,

And use of service, none; contract, succession,

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none;

No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil;

No occupation; all men idle, all,

And women too, but innocent and pure;

No sovereignty —

All things in common nature should produce

Without sweat or endeavor. Treason, felony,

Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine

Would I not have; but nature should bring forth

Of its own kind all foison, all abundance,

To feed my innocent people.

I would with such perfection govern, sir,

T’excel the Golden Age.

“OF CANNIBALS” THE TEMPEST

15 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

A Farewell

to Arts

PHOTO: JENNY GRAHAM

Four of his last plays — Pericles,

Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale

and The Tempest — are often

grouped under an umbrella genre

called romance or tragi-comedy.

As the latter label suggests, the

plays contain features of tragedy

(mistakes, crimes, disasters) and

comedy (abundance of humor,

marriage, happy endings). The

label romance, however, better

hints at the adventure these plays

oer: shipwrecks, faked deaths,

time jumps, magic, long-lost

children, deity cameos and more.

Shakespeare didn’t invent the

romance; it was merely a new

fashion in the theater built on an

old story form that he adopted

and, as with much that he touched,

improved on. Perhaps he was bored

playing by the rules of history,

comedy and tragedy and leaped

at the chance to mix it up and take

on a new challenge. In discussing

The Winter’s Tale, actor-director-

critic Harley Granville-Barker

called it “essentially the product of

middle age. … The technique of it is

mature, that of a man who knows

he can do what he will.”

One of the most compelling

features of Shakespeare’s

romances is a restored sense of

balance and harmony at the play’s

end in the form of forgiveness and

reconciliation. (One could argue

that tragedies such as Hamlet,

Macbeth and King Lear end in

balance restored, but the cost is

high and usually quite bloody.)

In a romance, a character who

makes a major mistake early in the

play — or before the play begins, in

the case of The Tempest — suers

through trials but receives at least

partial reparation for their troubles

and usually emerges the wiser.

Literary critic Northrop Frye notes

that the romances operate on

a smaller scale; the characters

and ideas may be kindred with

earlier tragedies, but the scope

is dierent. The grandness and

complexity of characters such as

Hamlet or Lear aren’t found in

these plays, and while the plots

may contain jealousy or ambition,

it’s not Othello-level jealousy or

Macbeth-level ambition. Perhaps

it’s their scale that enables

their reconciliations.

While Shakespeare’s four romances

have much in common, they aren’t

cookie-cutter stories, and The

By Carla Steen

Resident Dramaturg

William Shakespeare is

generally thought to have

written his plays between

1589 and 1613. In those 24

years, he created nearly 40

plays, a few in collaboration.

The Tempest is usually

dated to 1611, so it is not

only a mature work, it is a

very late play and likely the

last play he wrote alone.

Scenes From Shakespeare’s Romance Plays

Jennie Greenberry as Marina and Wayne T. Carr as Pericles in the Guthrie’s

2016 production

Pericles

PLAY FEATURECULTURAL CONTEXT

16 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

Tempest has some singular features.

For the first time since his early play

The Comedy of Errors, Shakespeare

constructs a play that adheres to

the unities of time, place and action.

The whole of the play unfolds over

just a few afternoon hours and

takes place almost exclusively on

Prospera’s island. And the action

drives toward characters being

reunited and just deserts being

delivered. Where other romances

feature long-lost daughters (Perdita

in The Winter’s Tale, Marina in

Pericles), Miranda is never lost nor

unknown to her parent; rather,

Prospera herself has been thought

lost and is reunited, if ambivalently,

with her brother, Antonio.

Also distinctive about The Tempest

when compared to the body of

Shakespeare’s work — not just

the romances — is that it has

an original plot, joining a small

subgroup of plays that includes

only The Merry Wives of Windsor

and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The Tempest may have been

inspired by then-contemporary

shipwrecks among early European

colonial expeditions to the

Americas and Africa. Especially in

recent generations, the themes of

colonialism and the treatment of

Indigenous cultures central to the

play have been brought to the fore

in the design of many productions.

But perhaps the characteristic

of The Tempest that most often

captures the imaginations of

interpreters and audiences alike is

its place so late in Shakespeare’s

career. Did he know this would

be his last solo work for the

stage? It’s almost impossible to

resist imagining that he did; in its

construction can be found a play-

length metaphor for playwriting (or

indeed for any artmaking).

Prospera spends years studying,

developing and then perfecting her

craft of magical arts, which allows

her to become the ruling power

of her island. Having achieved her

goal, she eventually gives up her

art when her own native dukedom

is restored to her. It’s not a stretch

to see in this character a shadow

of Shakespeare himself: He spent

years in his craft, developing and

perfecting his dramatic art and

reaching the pinnacle of theater

on his island. Eventually, having

achieved what he could, he gave

up the theater and returned to his

own native Stratford.

Especially in The Tempest’s

Epilogue, in which Prospera (or

the actor playing her) addresses

the audience directly, does this

playwright’s farewell seem evident.

“But release me from my bands/

With the help of your good hands”

puts the power firmly in the

applause of the audience to free

Prospera from her island and the

actor from the theater.

It also provides a final ovation for a

playwright leaving his profession.

Bill McCallum as Polixenes, Michelle O’Neill as Hermione and Michael Hayden

as Leontes in the Guthrie’s 2011 production

The whole of the play unfolds over just

a few afternoon hours and takes place

almost exclusively on Prospera’s island.

The Winter’s Tale

PHOTO: T CHARLES ERICKSON

Scenes From Shakespeare’s Romance Plays

17 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

PLAY FEATURECULTURAL CONTEXT

Selected Glossary of Terms

ague — Fever, sickness

art — Magic, both the learning and

practice of; also, the trickery and

artifice associated with magic

blue-eyed — At a time when grey

or black eyes were the standard in

beauty, blue eyes or blue eyelids

were associated with witches

boatswain — A ship’s ocer in

charge of the crew’s work and the

ship’s equipment, such as sails,

rigging and ropes

brave — Excellent, splendid, fine,

handsome

butt — Barrel, as in a wine cask

Ceres — In Roman mythology, the

goddess of the earth and agriculture

(associated with Demeter in Greek

mythology) and the mother of

Persephone; a Mother Earth figure

charm — Verbal magic; sometimes

a thing imbued with magic. In

Shakespeare, charms are often

connected with music and work

with a natural inclination, such as

sleepiness or remorse.

chess — A board game of strategy

that originated in sixth-century India,

moved to the Middle East and then

to Europe. Because of its popularity

among the nobility, it became known

as the “royal game” or “the game

of kings.” (The English word chess

derives from the Persian word shah,

which means “king.”) Naples was a

center for playing chess.

dolor — Grief, suering

entertainment — Hospitality,

treatment

fathom — Approximately 6 feet;

“full fathom five” is 30 feet

flamed amazement — A terrifying

flash of light. In The Tempest, Ariel

is likely recreating the weather

phenomenon of St. Elmo’s fire,

where static electricity can appear

during certain conditions. It creates

a faint light or glow on the points

of certain objects, such as a ship’s

mast during a storm.

Hagseed — A child (seed) of a

witch (hag)

Iris — In Greek mythology, the

goddess (or personification) of the

rainbow. She was a messenger of

the gods, especially connected to

Juno, and she used the rainbow as

her route of transportation.

Jove — Another name for Jupiter;

in Roman mythology, the chief

god, husband-brother of Juno

and equivalent of Zeus in Greek

mythology. As the lord of heaven

and bringer of light, he was known

for his lightning bolts.

Juno — In Roman mythology, the

queen of the gods (associated

with Hera in Greek mythology),

Ceres’ sister and Jupiter’s wife. She

is associated with marriage and

motherhood.

league — Approximately 3 miles

liberal arts — The seven subjects

of study during the rise of the

medieval university system:

the Trivium (grammar, logic

and rhetoric) and Quadrivium

(arithmetic, geometry, music/

harmonics and astronomy)

man i’th’moon — Tradition has

it that the man in the moon has a

dog and carries a bundle of sticks

picked up on a Sunday.

mooncalf — Calves born with

deformities were believed to be

under the moon’s malign influence.

The term was also used to describe

mentally or physically disabled

people who were thought to

have experienced adverse lunar

influence while in the womb.

Neptune — In Roman mythology,

the god of the sea and Jupiter’s

brother (known as Poseidon in

Greek mythology); sometimes his

name was used for the sea itself.

He was frequently depicted with

his three-pointed trident.

perfidious — Treacherous, disloyal

prince — A sovereign ruler,

sometimes used specifically for a

ruler of a small state, which is then

subject to a king

signories — Territories, specifically

Italian city-states

supplant — Uproot, remove, usurp

trumpery — Fancy garments, or

perhaps worthless finery

Sources include notes to The New Cambridge Shakespeare and The Arden Shakespeare editions of the play; Shakespeare’s Words by David

Crystal and Ben Crystal; Encyclopedia Britannica; Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable; Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare; Shakespeare’s

Demonology: A Dictionary; and Oxford English Dictionary.

18 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

PLAY FEATURE

EDUCATION RESOURCES

Discussion Questions

and Activities

THE ROLE OF GENDER IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS

It is common knowledge that during William Shakespeare’s life, his plays were performed by a cast of entirely

male actors. Even female roles were depicted by cisgender men.

“In 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, the prohibition of public acting by women and the

convention of all-male casting were peculiar to England. Though easily accepted by audiences,

the playing of female roles by boys led writers to emphasize the femininity of women in their

plays to an extent that the use of female performers would have rendered unnecessary.”

From The Arden Shakespeare edited by Richard Proudfoot, Ann Thompson and David Scott.

Kastan, 1998. Reprinted, 2000.

In contemporary theater, female roles are generally played by women. In recent years, many female actors have

taken on significant male roles, thus subverting tradition and lending new perspectives to the role of gender in

Shakespeare’s plays.

Discussion Questions

The lead character in The Tempest — Prospero — was written as a man, a father and former duke of Milan. In this

Guthrie production, the role has been changed to Prospera and is played by local actor Regina Marie Williams.

The characters of Gonzalo and Francisco are also played as women (Gonzala and Francisca), while the character

of Trinculo is played as a man by a cisgendered woman.

• What did you notice about the role of gender in Shakespeare’s The Tempest?

• How would you describe the character of Prospero/Prospera? What about this character stands out as being

particularly masculine or feminine?

• Which character in the play did you find most interesting or most complex — and why?

• Do you think Shakespeare’s female characters reflect the same amount of depth or complexity as his male

characters? Do you believe Shakespeare would have written more complex female characters into his plays if

he had been able to cast female or nonbinary actors?

Online Activity: A Letter From the Director

Imagine it is early 17th-century England, and you are the director of The Tempest.

• OPTION ONE: Write a letter to the boy who will be playing Miranda.

• OPTION TWO: Write a letter to the woman who will be playing Prospero, a male character.

Explain what they will need to know in order to portray this character as believably as possible. Feel free to

include any special instructions or advice in your letter.

19 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

Classroom Activity: Stepping Into the Role

Besides gender, there are other ways an actor may personally dier from the character they portray onstage. At

times, an actor may be cast as a character whose experiences are rather dissimilar from their own. In such cases,

the actor may need to do a significant amount of research to connect with their character and better understand

their point of view before stepping into the role. The actor may seek out a real-life person who shares some of

the character’s particular life experiences. The actor will listen and ask questions in an eort to see the world

through that person’s eyes.

For this activity, place students in groups of two (or three, if needed). For ease of explanation, the following

instructions refer to Student A and Student B within each group. NOTE: If in a group of three, repeat the

instructions below with Students B and C.

Student A: Think of a specific memory from your life when you were in a natural environment (at a lake, at the

beach, in the woods, at a park). Describe this one experience to Student B in as much detail as possible for 5–7

minutes. It can be any memory you are willing to share and that you can recall in vivid detail.

Student B: Listen for details and take time to write a few notes for yourself to help you remember key aspects

of the story. Ask Student A questions about the environment, people or animals involved or any specifics about

the action. Then put your notes down. As you are able, get on your feet and act out this memory as if you are

reliving it as Student A. Go through the actions, see the sights, hear the sounds and recall the thoughts and

emotions that Student A described in their story. Bring them to life as if they were your own.

Student A: Sit quietly and observe like an audience. This is Student B’s interpretation of your story, and it’s okay

if some aspects are reimagined!

Student B: Try another version of the storytelling where you recreate the experience just physically in space

without using words.

Students A and B: Come together and discuss.

• For Student B: Were any of the thoughts, emotions or experiences familiar to you? Did acting it out make it

feel more familiar than when you were just listening to the story?

• For Student A: What was it like to have a segment of your life played out in front of you?

Discuss the following questions as a group:

• Is it important for you to see someone onstage who reminds you of yourself?

• What does it mean for someone with a very dierent life experience to portray your story?

PHOTO: LAAKAN McHARDY, JOHN KROFT AND REGINA MARIE WILLIAMS (DAN NORMAN) PHOTO: HARRY SMITH (DAN NORMAN)

20 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

A WORLD OF HUMANS AND SPIRITS

“Only by gaining control of the spirits who manage the functioning of the

natural world can a man accomplish what Prospero does; Ariel is a necessary

intermediary. As such, he leaves Prospero’s humanity intact.”

From “Prospero: Master of Self-Knowledge” by Barbara Howard Traister. Heavenly

Necromancers: The Magician in English Renaissance Drama, 1984.

Discussion Questions

• How would you describe the role of Ariel in Shakespeare’s The Tempest? What kind of parallels could be made

between Ariel’s magic and the magic of theater?

• How does Prospera embrace her human abilities and limitations? What does she desire most at the beginning of the

play, and how do her priorities change by the end of the play? Would you describe her journey as transformative?

• How much of Caliban’s behavior stems from his resentment toward having been forced into servitude? Where

might you find humanity in the character of Caliban?

• Which character in the play did you care about the most? What made you sympathize with them? At what

point in the play did you feel most concerned about their situation or about what was going to happen next?

Online Activity: Heroes and Villains

The Tempest falls in the genre of romance/tragi-comedy where typical expectations of heroes and villains might be

subverted. For example, if The Tempest played out as the revenge drama it initially appears to be, would Prospera be a

villain? Since she doesn’t take revenge and the play turns toward a happy ending, is Prospera a hero? Given the events

that occurred in Milan 12 years ago, is Antonio a villain? Is there a point of view that is more sympathetic to him? Is the

same true of Sebastian as he plots to murder Alonso on the island? Or are there degrees of villainy and heroism?

Ask students to write freely for 15 minutes based on these prompts: What makes a character a hero? What makes

a character a villain? Does it depend on the point of view from which the story is told? Choose two characters from

the play and write about why you believe each to be a hero or a villain. If there were one action that each character

could take (or do dierently) that would cause you to categorize them as the opposite, what would that action be?

If it is possible for a villain to become a hero, what circumstances are necessary for that chance to take place?

Classroom Activity: Poetry in Shakespeare

Have you ever tried to explain how you were feeling to someone and struggled to find the words? Symbolism,

simile and metaphor can help communicate those big thoughts and feelings! Shakespeare uses poetic language

when everyday language does not suce to convey a particular idea or emotion. For the following activity,

students may work individually and then share their ideas with the class.

The Tempest begins with a pivotal “natural” event — a storm. Shakespeare uses the symbolism of this force of

nature to turn the world upside down for most characters in the play. Invite students to think of a change in

their life that felt significant, and have them draw a picture or write a poem (in any form) that illustrates their

experience of that event using only language that has to do with nature or natural occurrences (thunderstorms,

lightning, blossoming flowers, falling leaves, crashing waves). Students may also choose one emotion (joy,

sorrow, frustration) and draw or write about it using images found in nature.

The play itself is an extended metaphor for an artist’s work. As an expansion of this exercise, ask students to

search the text for expressions of poetry or imagery that point back to the theatrical metaphor.

Discuss the following questions as a group:

• What does it feel like to use poetic language and symbolism from the natural world to describe your

circumstances or experiences?

• What were your impressions of your classmates’ pictures and poems?

• Did you relate to any of their experiences as described? If so, how?

21 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST

For Further Reading

and Understanding

ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION

EDITIONS OF THE TEMPEST

The Tempest edited by David Lindley. The New Cambridge

Shakespeare.

The Tempest edited by Virginia Mason Vaughan and Alden T.

Vaughan. The Arden Shakespeare.

FILMS

Tempest, adapted by Paul Mazursky and Leon Capetanos, directed

by John Cassavetes. Starring Cassavetes as Phillip, Gena

Rowlands as Antonia, Susan Sarandon as Aretha, Raul Julia as

Kalibanos and Molly Ringwald as Miranda. 1982.

Prospero’s Books, adapted and directed by Peter Greenaway.

Starring John Gielgud as Prospero, Isabelle Pasco as Miranda,

Tom Bell as Antonio and Mark Rylance as Ferdinand. 1991.

The Tempest, directed by Julie Taymor. Starring Helen Mirren as

Prospera, Felicity Jones as Miranda, Djimon Hounsou as Caliban,

Ben Whishaw as Ariel and Chris Cooper as Antonio. 2010.

BOOKS (General Shakespeare Studies)

Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare (two volumes) by Issac Asimov.

Avenel Books, 1970.

Lectures on Shakespeare by W. H. Auden. Princeton University

Press, 2000.

Shakespeare’s Great Stage of Fools by Robert H. Bell. Palgrave

Macmillan, 2011.

Pronouncing Shakespeare’s Words: A Guide From A to Zounds

by Dale F. Coye. Greenwood Press, 1998.

Shakespeare’s Words: A Glossary and Language Companion

by David and Ben Crystal. Penguin Books, 2002.

Shakespeare’s Songbook by Ross W. Dun. W. W. Norton &

Company, 2004.

Shakespeare After All by Marjorie Garber. Pantheon, 2004.

Prefaces to Shakespeare by Harley Granville-Barker. Princeton

University Press, 1947.

Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare by

Stephen Greenblatt. W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Shakespeare’s Motley by Leslie Hotson. Haskell House Publishers,

1971.

Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? by James Shapiro.

Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Passing Strange: Shakespeare, Race and Contemporary America

by Ayanna Thompson. Oxford University Press, 2011.

WEBSITES

Folger Shakespeare Library. A wealth of resources, including

lesson plans, study guides and interactive activities.

www.folger.edu

Shakespeare Unlimited. A biweekly podcast produced by

the Folger Shakespeare Library that features interviews

with Shakespeare experts on topics ranging from adapting

Shakespeare to what Elizabethans ate to discussions about

current productions.

www.folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited

Internet Shakespeare Editions. A collection of materials on

Shakespeare and his plays, an extensive archive of productions

and production materials.

http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/index.html

Shakespeare Uncovered. A series that goes in-depth into one play

per episode. A host with a personal tie to the play investigates

the text and its interpretations and visits companies in rehearsal

and in performance. Episodes may be available online. The

Tempest was included in the first season hosted by theater

director Trevor Nunn.

www.pbs.org/wnet/shakespeare-uncovered

MIT Shakespeare: The Complete Works Online

http://shakespeare.mit.edu

PlayShakespeare.com: The Ultimate Free Shakespeare Resource.

After registration, receive access to the full texts of the plays,

synopses, the First Folio and study aids. An accompanying

smartphone app features full texts of the plays.

www.playshakespeare.com

PHOTO: STEPHEN YOAKAM WITH BILL McCALLUM (DAN NORMAN)

22 \ GUTHRIE THEATER PLAY GUIDE THE TEMPEST