Assessment PracticesAssessment Practices

Assessment PracticesAssessment Practices

Assessment Practices

inin

inin

in

Foreign Language EducationForeign Language Education

Foreign Language EducationForeign Language Education

Foreign Language Education

DIMENSION 2004DIMENSION 2004

DIMENSION 2004DIMENSION 2004

DIMENSION 2004

Lynne McClendon

Rosalie M. Cheatham

Denise Egéa-Kuehne

Carol Wilkerson

Judith H. Schomber

Jana Sandarg

Scott T. Grubbs

Victoria Rodrigo

Miguel Mantero

Sharron Gray Abernethy

Editors

C. Maurice CherryC. Maurice Cherry

C. Maurice CherryC. Maurice Cherry

C. Maurice Cherry

Furman University

Lee BradleyLee Bradley

Lee BradleyLee Bradley

Lee Bradley

Valdosta State University

Selected Proceedings of the 2004 Joint Conference of the

Southern Conference on Language Southern Conference on Language

Southern Conference on Language Southern Conference on Language

Southern Conference on Language

TT

TT

T

eachingeaching

eachingeaching

eaching

and the Alabama Association of Foreign Language Teachers

ii

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

© 2004 Southern Conference on Language Teaching

SCOLT Publications

1165 University Center

Valdosta State University

Valdosta, GA 31698

Telephone 229 333 7358

Fax 229 333 7389

http://www.valdosta.edu/scolt/

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

in any form or by any means, without

written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 1-883640-17-2

Valdosta State University provided equipment and facilities

in support of the work of

preparing this volume for press.

iii

TT

TT

T

ABLE OF CONTENTSABLE OF CONTENTS

ABLE OF CONTENTSABLE OF CONTENTS

ABLE OF CONTENTS

Review and Acceptance Procedures .............................................................iv

2004 SCOLT Editorial Board ........................................................................v

Introduction ................................................................................................. vii

Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... x

Announcement:

AA

AA

A

Special Series on Special Series on

Special Series on Special Series on

Special Series on

Assessment Assessment

Assessment Assessment

Assessment . ......................................xi

No Child Left Behind in ForeignNo Child Left Behind in Foreign

No Child Left Behind in ForeignNo Child Left Behind in Foreign

No Child Left Behind in Foreign

Language Education Language Education

Language Education Language Education

Language Education . .........................................................

11

11

1

Lynne McClendon

Using Learner and Using Learner and

Using Learner and Using Learner and

Using Learner and

TT

TT

T

eacher Preparationeacher Preparation

eacher Preparationeacher Preparation

eacher Preparation

SS

SS

S

tandards to Reform a Language Major tandards to Reform a Language Major

tandards to Reform a Language Major tandards to Reform a Language Major

tandards to Reform a Language Major . ........................

99

99

9

Rosalie M. Cheatham

SS

SS

S

tudent Electronic Portfolio tudent Electronic Portfolio

tudent Electronic Portfolio tudent Electronic Portfolio

tudent Electronic Portfolio

Assessment Assessment

Assessment Assessment

Assessment . ......................

1919

1919

19

Denise Egéa-Kuehne

Assessing Readiness of Foreign Language EducationAssessing Readiness of Foreign Language Education

Assessing Readiness of Foreign Language EducationAssessing Readiness of Foreign Language Education

Assessing Readiness of Foreign Language Education

Majors to Majors to

Majors to Majors to

Majors to

TT

TT

T

ake the Praxis II Examake the Praxis II Exam

ake the Praxis II Examake the Praxis II Exam

ake the Praxis II Exam . ...............................

2929

2929

29

Carol Wilkerson, Judith H. Schomber,

and Jana Sandarg

The The

The The

The

TPR TPR

TPR TPR

TPR

TT

TT

T

est: est:

est: est:

est:

TT

TT

T

otal Physical Responseotal Physical Response

otal Physical Responseotal Physical Response

otal Physical Response

as an as an

as an as an

as an

Assessment Assessment

Assessment Assessment

Assessment

TT

TT

T

oolool

oolool

ool . .....................................................

4343

4343

43

Scott Grubbs

Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening:Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening:

Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening:Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening:

Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening:

SS

SS

S

tudents’tudents’

tudents’tudents’

tudents’

Perceptions and Performance Perceptions and Performance

Perceptions and Performance Perceptions and Performance

Perceptions and Performance . .......................

5353

5353

53

Victoria Rodrigo

Accounting for Accounting for

Accounting for Accounting for

Accounting for

Activity: Cognition andActivity: Cognition and

Activity: Cognition andActivity: Cognition and

Activity: Cognition and

Oral Proficiency Oral Proficiency

Oral Proficiency Oral Proficiency

Oral Proficiency

Assessment Assessment

Assessment Assessment

Assessment . ..........................................

6767

6767

67

Miguel Mantero

Building Bridges for International Internships Building Bridges for International Internships

Building Bridges for International Internships Building Bridges for International Internships

Building Bridges for International Internships . ...........

8585

8585

85

Sharron Gray Abernethy

SCOLT Board of Directors 2003-2004 .............................

101101

101101

101

Advisory Board of Sponsors and Patrons 2003 ................

102102

102102

102

Previous Editions of

Dimension .......................................

108108

108108

108

11

11

1

22

22

2

33

33

3

44

44

4

55

55

5

66

66

6

77

77

7

88

88

8

iv

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

Review and Review and

Review and Review and

Review and

Acceptance ProceduresAcceptance Procedures

Acceptance ProceduresAcceptance Procedures

Acceptance Procedures

SCOLSCOL

SCOLSCOL

SCOL

TT

TT

T

DimensionDimension

DimensionDimension

Dimension

The procedures through which articles are reviewed and accepted for publica-

tion in the proceedings volume of the Southern Conference on Language Teaching

(SCOLT) begin with the submission of a proposal to present a session at the SCOLT

Annual Conference. Once the members of the Program Committee have made their

selections, the editors invite each presenter to submit the abstract of an article that

might be suitable for publication in

Dimension

, the annual volume of conference

proceedings.

Only those persons who present

in person

at the annual Joint Conference are

eligible to have written versions of their presentations included in

Dimension

. Those

whose abstracts are accepted receive copies of publication guidelines, which fol-

low almost entirely the fifth edition of the

Publication Manual of the American

Psychological Association

. The names and academic affiliations of the authors and

information identifying schools and colleges cited in articles are removed from the

manuscripts, and at least four members of the Editorial Board and the co-editors

review each of them. Reviewers, all of whom are professionals committed to sec-

ond language education, make one of four recommendations: publish as is, publish

with minor revisions, publish with significant rewriting, or do not publish.

The editors review the recommendations and notify all authors as to whether

their articles will be printed. As a result of these review procedures, at least three

individuals decide whether to include an oral presentation in the annual confer-

ence, and at least six others read and evaluate each article that appears in

Dimen-

sion

.

v

2004 SCOL2004 SCOL

2004 SCOL2004 SCOL

2004 SCOL

TT

TT

T

Editorial Board Editorial Board

Editorial Board Editorial Board

Editorial Board

Theresa A. Antes Sheri Spaine Long

University of Florida University of Alabama at Birmingham

Gainesville, FL Birmingham, AL

Jean-Pierre Berwald Joy Renjilian-Burgy

University of Massachusetts Wellesley College

Amherst, MA Wellesley, MA

Karen Hardy Cárdenas Jean Marie Schultz

South Dakota State University University of California, Santa Barbara

Brookings, SD Santa Barbara, CA

A. Raymond Elliott Anne M. Scott

University of Texas at Arlington SUNY-Cortland

Arlington, TX Cortland, NY

Carine Feyten John Underwood

University of South Florida Western Washington University

Tampa, FL Bellingham, WA

Cynthia Fox Ray Verzasconi

University at Albany (SUNY) Oregon State University, emeritus

Albany, NY Portland, OR

Carolyn Gascoigne Joel Walz

University of Nebraska at Omaha University of Georgia

Omaha, NE Athens, GA

Virginia Gramer Richard C. Williamson

Consolidated School District #181 Bates College

Hinsdale, IL Lewiston, ME

Norbert Hedderich Helene Zimmer-Loew

University of Rhode Island American Association of

Kingston, RI Teachers of German

Cherry Hill, NJ

Paula Heusinkveld

Clemson University

Clemson, SC

vi

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

REMOVE HEADER line, leave the “vi”

vii

IntroductionIntroduction

IntroductionIntroduction

Introduction

One of the most onerous, yet critical tasks facing members of the Board of

Directors of the Southern Conference on Language Teaching (SCOLT) is that of

selecting a theme well in advance of each annual conference. Given the current

climate of demands for accountability and reform at national, state, and local levels

in both K-12 and post-secondary institutions, “Assessment Practices in Foreign

Language Education” seemed particularly timely as the theme for the 2004 SCOLT

meeting, March 18-20, in Mobile, Alabama. Although the invitation for presenters

to submit abstracts for articles to be considered for publication clearly stated that

authors were not required to address this topic, each of the contributions most

highly recommended by our Editorial Board for inclusion in this volume dealt with

the theme, either in part or almost exclusively.

Before readers begin perusing the eight primary articles in this collection, the

editors urge them to pay special attention to the announcement on pp. xi-xv, where

Lynne McClendon and Carol Wilkerson introduce a new series of articles on as-

sessment, to include an annotated bibliography on the subject in the 2005 volume

of

Dimension.

The authors also provide an overview of the two agencies approved

to accredit teacher education programs–the National Council for Accreditation of

Teacher Education (NCATE) and the Teacher Education Accreditation Council

(TEAC)–and explain how certification requirements, teacher licensure, and man-

datory tests vary across the states in the SCOLT region.

Touted at its inception as a major educational policy reform at the national

level and hailed by many as a much-needed initiative to mandate the kind of change

required to diminish many of the inequities in public education and hold states,

districts, and even individual schools accountable for the failure of their students to

demonstrate sufficient progress, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB)

quickly became a political football. The legislation attracted intense criticism once

results of high-stakes testing and other criteria used as evidence of success or fail-

ure showed that many schools and districts were not making the grade in terms of

mandated progress goals, often because of the obvious inconsistencies in estab-

lishing similar goals for otherwise comparable schools and districts. Nevertheless,

NCLB is a reality, and individual teachers, schools, and districts currently have

little recourse but to make every effort to comply with both the spirit and the letter

of the law. In “No Child Left Behind in Foreign Language Education,” Lynne

McClendon provides an overview of the law as it affects second language (L2)

teachers. More specifically, though, she examines in detail one of the key phrases

in the legislation, “highly qualified teachers,” as it is defined by the law, explores

ways in which current and aspiring L2 teachers and their administrators and super-

visors can assess progress being made towards meeting the goals of the NCLB act,

and suggests ways in which they can ensure that they are complying with the law in

a timely fashion.

Academic territoriality, parochial interests, and, on occasion, sheer paranoia

often lead to the maintenance of a curricular status quo in higher education, thereby

viii

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

resulting in total stagnation of course offerings and program development. Despite

the fact that L2 programs at numerous colleges and universities have made consid-

erable progress in having their courses reflect the latest philosophies concerning

L2 acquisition, the transformation of the overall curriculum design of a particular

department or program in many cases shows little evidence of change over a period

of two or more decades. In “Using Learner and Teacher Preparation Standards to

Reform a Language Major,” Rosalie Cheatham explores the ways in which a for-

eign language department at one large university assessed its need for reform and

overhauled its curriculum to bring it more closely in line with current best prac-

tices, with attention to existing L2 standards and the specific needs of those en-

rolled in teacher education programs.

Portfolio review has become a mainstay of assessment tools at many educa-

tional levels. In “Student Electronic Portfolio Assessment,” Denise Egéa-Kuehne

provides an overview of the terminology related to assessment and discusses some

of the ways in which program assessment and evaluation have been practiced with

varying degrees of success in recent years. The author then cites both advantages

and limitations of using the electronic portfolio as a mechanism for assessing the

progress of individual students. Of particular value to those interested in undertak-

ing a similar venture is the concrete information the author provides concerning

both the organization of such a program and the specific list of technological tools

essential to the successful implementation of electronic portfolio assessment.

Few experiences prove so disheartening to an aspiring teacher as that of com-

pleting a prescribed program of course work and perhaps even a teaching intern-

ship, only to receive a score falling below the established minimum on a mandatory

standardized test. Just when such would-be teachers see themselves as being on the

threshold of beginning a career in L2 education, they see their dreams shattered.

One of the issues of greatest concern to those preparing teachers for qualifying

exams is the inconsistency among states in terms of both the specific tests being

required and the discrepancies in cutoff scores from one state to another. Of equal

concern is the nature of the specific exams in terms of content and delivery of

questions. In “Assessing Readiness of Foreign Language Education Majors to Take

the Praxis II Exam,” Carol Wilkerson, Judith Schomber, and Jana Sandarg survey

such inequities and concerns and offer concrete recommendations as to how candi-

dates for certification can best prepare themselves to achieve acceptable test scores.

“Total Physical Response” has become such a staple in the vocabulary of L2

educators that it is most commonly simply referred to as “TPR,” and the term

“Total Physical Response Storytelling” (TPRS) has more recently become almost

as widely known. Long an integral component of language programs in elementary

schools, TPR has in recent years been integrated into the curricula of language

classes for more mature learners. Nevertheless, the use of TPR both as a compo-

nent of the overall assessment process for individual language development and as

a measure of programmatic success has to date received insufficient recognition, as

Scott Grubbs reminds readers in “The TPR Test: Total Physical Response as an

Assessment Tool.” The author further argues convincingly that in addition to being

an effective pedagogical vehicle during early language instruction and a viable

ix

evaluation instrument, TPR can be used to appeal to the multiple intelligences of a

diverse population of language learners.

A survey of the majority of methods texts and bibliographies of articles on L2

education reveals that the amount of literature on listening comprehension in L2

education generally pales in comparison to that available on the speaking, reading,

and writing skills. Therefore, any contribution in the area of developing listening

skills is particularly welcome if it adds something fresh, as is the case in Victoria

Rodrigo’s “Assessing the Impact of Narrow Listening: Students’ Perceptions and

Performance.” After surveying previous findings concerning the role of listening in

L2 learning, the author defines “narrow listening” (NL), provides a framework for

the systematic integration of NL into the L2 curriculum, and shares guidelines for

the development of the audio library critical to the success of the NL approach.

Finally, the author provides positive results from an assessment of both students’

perceptions of the approach and the effects of NL on their actual listening skills, as

measured by an aural comprehension test.

In “Accounting for Activity: Cognition and Oral Proficiency Assessment,”

Miguel Mantero examines another of the basic L2 skills, speaking, both with refer-

ence to the specific ways in which cognition plays a role in the assessment of speaking

proficiency, according to the

ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines,

and with respect to

determining the degree to which cognition should be a fundamental part of any

assessment of oral proficiency. Through a meticulous analysis of several oral pro-

ficiency interviews and collaboration with an external evaluator solicited to pro-

vide an objective point of view, the author concludes that cognition must occupy a

more central role in assessment of speaking proficiency and recommends that class-

room instructors make use of

instructional conversations

and a framework of

in-

digenous assessment criteria

to enhance the abilities of their students to demon-

strate greater overall proficiency.

Because prospective employers and admissions committees continue to raise

their expectations of job applicants and candidates for admission to graduate pro-

grams and professional schools, college students make increasing demands on their

institutions to provide a more extensive range of internships, as is particularly the

case for those eager to integrate their interests in business and L2 study. In “Build-

ing Bridges for International Internships,” Sharron Abernethy details the structure

of one university’s language/business internship program, describes the procedure

by which it was assessed, and in several appendices shares both a syllabus and a

number of forms that may prove useful as models for those interested in develop-

ing similar programs at their institutions.

We believe that L2 professionals at all levels will view this volume as a di-

verse collection of informative articles, but we hope that readers will find them

truly enjoyable as well.

The Editors

Lee Bradley Maurice Cherry

Valdosta State University Furman University

Valdosta, GA Greenville, SC

x

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

AcknowledgmentsAcknowledgments

AcknowledgmentsAcknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Among our greatest pleasures in preparing each volume of

Dimension

is that

of working with an Editorial Board as generous with its time as it is knowledgeable

about the field of second language education. We continue to recruit reviewers

from within and beyond our SCOLT region, teachers of various languages at the

elementary level, in graduate schools, and at every stage in between. This year’s 19

readers hail from 16 different states and include those familiar with a broad range

of critical issues in second language education, research problems, legal concerns,

and a vast array of contemporary methodologies and instructional techniques. Our

reviewers are attentive to detail, and, in addition to their predictable role in citing

both the strengths and weaknesses of specific articles, many share with those whose

articles are to be published invaluable advice concerning potential references that

might otherwise have been overlooked, questions that should be addressed, and

recommendations for clarification of language or a change in focus in the treatment

of a particular subject.

It should go without saying that the authors deserve our praise as well, because

they have been willing to heed the advice of the reviewers, accepting most sugges-

tions in a positive way and in a few cases convincingly defending their original

observations. Even in the final days of our preparation of this volume, the editors

have had to communicate with almost all of the authors, in some cases requesting

clarification of a specific term or phrase and in others asking for a last-minute

update of a Web address or bibliographical reference. In every case the authors

have responded promptly and courteously.

Because many of those teaching second languages are less familiar with the

APA style than with other manuscript formats and since technological advances

have made citations of electronic references fairly complex, the task of double-

checking Web sources for accuracy and that of cross-checking text citations against

the References section of each article at times prove tedious. We therefore owe

special thanks to Donté Stewart, a Furman University undergraduate who has as-

sisted with the proofreading and verification of the many references in these ar-

ticles.

As always, the editors of

Dimension

and the SCOLT Board of Directors owe

our greatest debt to the Administration of Valdosta State University for having

made available to us the resources necessary for publication of this volume. With-

out such support,

Dimension 2004

would not exist in its present state.

Lee Bradley and

C. Maurice Cherry, Editors

Announcement:Announcement:

Announcement:Announcement:

Announcement:

Special Series on Special Series on

Special Series on Special Series on

Special Series on

AssessmentAssessment

AssessmentAssessment

Assessment

LL

LL

L

ynne McClendonynne McClendon

ynne McClendonynne McClendon

ynne McClendon

Executive Director

Southern Conference on Language Teaching

Carol Carol

Carol Carol

Carol

WW

WW

W

ilkersonilkerson

ilkersonilkerson

ilkerson

Carson-Newman College

On the eve of its 40th anniversary, the Southern Conference on Language Teach-

ing (SCOLT) plans a special series of articles on assessment within the foreign

language profession. The 2004 edition of

Dimension

offers an overview of the

instruments used to evaluate teacher education programs that prepare foreign lan-

guage teacher candidates and examines the teacher evaluation instruments required

for licensure in the SCOLT region. The series will continue in the 2005 edition of

Dimension

with an annotated bibliography of noteworthy and recommended ar-

ticles on assessment.

Accreditation of Accreditation of

Accreditation of Accreditation of

Accreditation of

TT

TT

T

eacher Education Programs: NCAeacher Education Programs: NCA

eacher Education Programs: NCAeacher Education Programs: NCA

eacher Education Programs: NCA

TE and TE and

TE and TE and

TE and

TEACTEAC

TEACTEAC

TEAC

There are two teacher education accrediting agencies approved by the U.S.

Department of Education. The National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Edu-

cation (NCATE) was founded in 1954 and was acknowledged as the only agency

responsible for accrediting teacher education programs in 1992. Over 500 institu-

tions have met NCATE accreditation standards, and 48 states have a partnership

with NCATE to conduct joint or concurrent reviews. The Teacher Education Ac-

creditation Council (TEAC) was founded in 1997 and recently received federal

acknowledgement as an accrediting agency by U.S. Secretary of Education Rod

Paige. There are currently three institutions that have undergone TEAC review and

several others in the review process. The difference between these two agencies

can be seen in their distinct approaches in verifying the validity of a teacher educa-

tion program and its ability to deliver knowledgeable and skilled P-12 teachers.

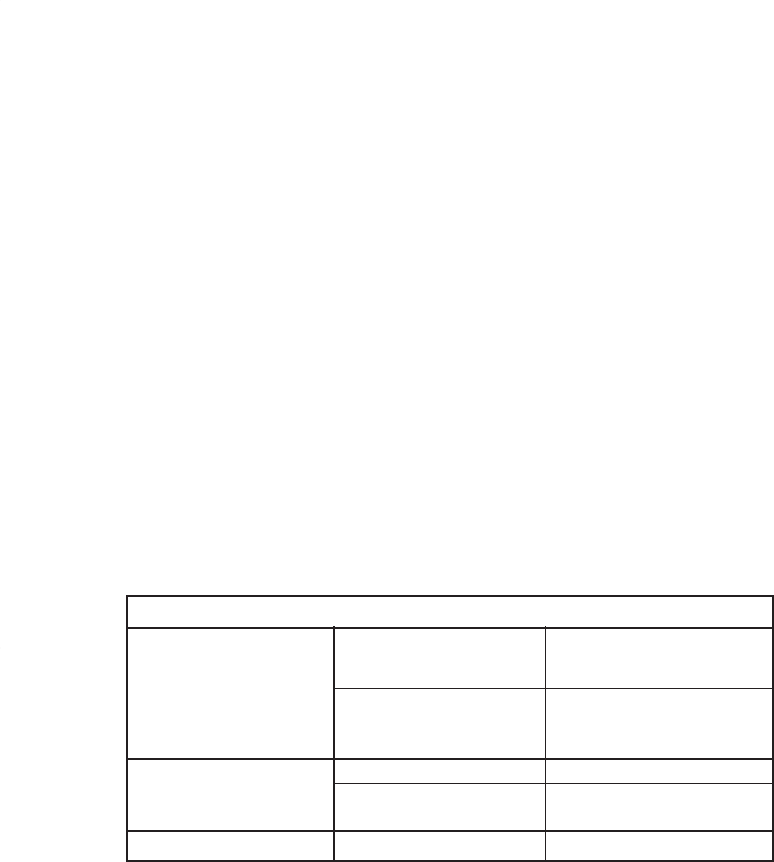

NCATE is a performance-based accreditation system. A paper review of an

institution’s teacher education program is conducted either by the state or by a

foreign language professional organization according to the agreement NCATE

has with the state of the institution making application for accreditation. A Board of

Examiners conducts an on-site visit to evaluate the capacity of the program to meet

standards of delivery. The following standards form the basis of the NCATE review:

xi

xii

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

I. Candidate Performance

Standard 1: Candidate knowledge, skills, and dispositions

Standard 2: Assessment system and unit evaluation

II. Unit Capacity

Standard 3: Field Experiences and Clinical Practice

Standard 4: Diversity

Standard 5: Faculty Qualifications, Performance, and Development

Standard 6: Unit Governance and Resources

After submitting the

Intent to Seek NCATE Accreditation

form and meeting

obligations required for this process, institutional programs seeking NCATE ac-

creditation must provide a program report no longer than 140 pages with a cover

letter, an overview section, response to the standards to be met, and appendices

with supporting documentation. The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign

Languages (ACTFL) partnered with NCATE to develop the specific foreign lan-

guage standards, using the rubrics “approaches standard,” “meets standard,” and

“exceeds standard” to qualify the applicant’s degree of meeting them. After a re-

view of the information submitted with the Board of Examiners’ report, NCATE

awards one of the following designations:

first accreditation

,

provisional accredi-

tation

,

continuing

accreditation

,

conditional accreditation

, or

accreditation with

probation

. Those interested in further information regarding the accreditation pro-

cess, should access the NCATE Web site at <http://www.ncate.org>.

The heart of the TEAC process is based on the examination of student learning

and on the quality of evidence submitted by an institution to support its claim that

students are meeting established learning objectives. Each component also has a

focus on learning how to learn, multicultural perspectives and accuracy, and tech-

nology. The following represent TEAC’s goals and principles:

Quality Principle I

1.0 Evidence of Student Learning

1.1 Subject matter knowledge

1.2 Pedagogical knowledge

1.3 Teaching skill

Quality Principle II

2.0 Valid Assessment of Student Learning

2.1 Evidence of links between assessments and the program goal, claims,

and requirements

2.2 Evidence of valid interpretations of assessment

Quality Principle III

3.0 Institutional Learning

3.1 Program decisions and planning based on evidence

3.2 Influential quality control system

Announcement: Special Series on Assessment xiii

Standards of Capacity for Program Quality

4.1 Curriculum

4.2 Faculty

4.3 Facilities, Equipment, and Supplies

4.4 Fiscal and Administrative

4.5 Student Support Services

4.6 Recruiting and Admissions Practices, Academic Calendars, Catalogs,

and Publications

4.7 Student Complaints

A major component of the TEAC process involves the

Inquiry Brief

prepared

by the institution undergoing evaluation. This academic piece must describe clear

and evaluative goals for student learning and the application of these goals in cur-

riculum design and pedagogy, evidence of student learning, the way in which the

institution allows for continuous improvement, and the strength of the seven ca-

pacity standards. TEAC sends trained auditors to the institution to conduct the site

visit through a thorough investigation of the

Inquiry Brief

, including a request for

raw data to verify the claims made in this document. During the audit visit, the

institution has the opportunity to update important changes that may have taken

place since the submission of the

Inquiry Brief

. The audit team turns over its com-

pleted audit report to the Accreditation Panel to allow evaluation of the evidence in

order to determine which of the following categories of accreditation will be awarded

to the institution:

accreditation

,

new program

or

pre-accreditation

,

provisional

accreditation

, or

denied accreditation

. For further information regarding the TEAC

accreditation process and schools that have undergone this process, access the web

site at <http://www.teac.org>.

TT

TT

T

eacher Evaluation Instruments in the SCOLeacher Evaluation Instruments in the SCOL

eacher Evaluation Instruments in the SCOLeacher Evaluation Instruments in the SCOL

eacher Evaluation Instruments in the SCOL

TT

TT

T

Region Region

Region Region

Region

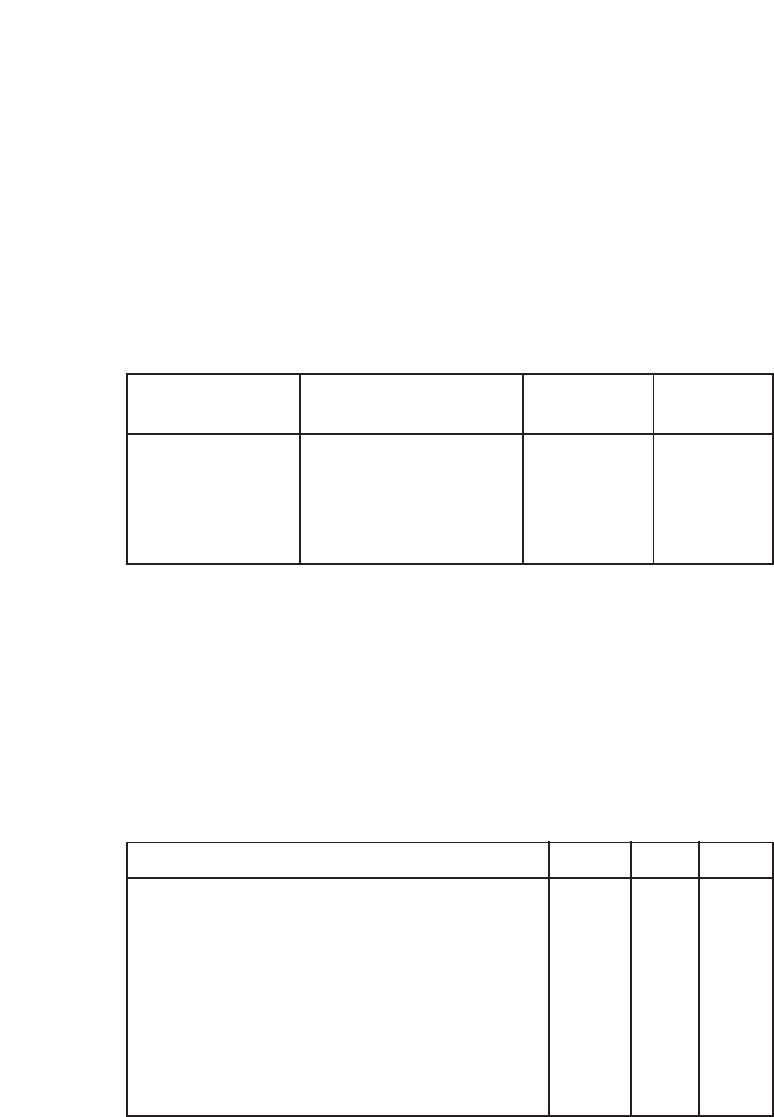

The 13 states that comprise the Southern Conference on Language Teaching

(SCOLT) differ in the languages for which they certify teachers and in their certifi-

cation requirements. To simplify matters, the discussion that follows examines

certification instruments for French, German, and Spanish. However, Web sites are

provided for the benefit of readers wishing information for other modern languages

and the classics.

In the SCOLT region all states except Alabama, Florida, and Texas require

teacher candidates to take the

Praxis II Exam

for licensure to teach French, Ger-

man, or Spanish. The

Praxis II Exam

is a series of exams developed and administered

by Educational Testing Service (ETS), a professional test development company

based in Princeton, New Jersey. State departments of education or agencies re-

sponsible for licensing specify which of the various component tests in the Praxis

Series will be used for certification, and they establish their state’s minimum pass-

ing scores.

xiv

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

The two most commonly required component tests are the Productive Lan-

guage Skills Test and the Content Knowledge Test. The Productive Language Skills

Test is a 2-hour test of candidates’ speaking and writing abilities. The Content

Knowledge Test is a 2-hour test of 120 multiple-choice questions, divided into four

sections. The first section evaluates interpretative listening; the second tests knowl-

edge of the structure of the target language; the third assesses interpretative reading;

and the fourth tests knowledge of cultural perspectives. Test-takers respond to ques-

tions about language and culture based upon tape-recorded listening passages and

printed material. Details about specific tests, languages not mentioned above, and

passing scores may be found at <www.ets.org/praxis/prxstate.html>.

Licensure in Licensure in

Licensure in Licensure in

Licensure in

Alabama, Florida, and Alabama, Florida, and

Alabama, Florida, and Alabama, Florida, and

Alabama, Florida, and

TT

TT

T

exasexas

exasexas

exas

Three states in the SCOLT region have their own, distinct licensure require-

ments. In Alabama, teacher candidates take a common basic skills test, but each

college or university designs its own comprehensive content exam for licensure.

This procedure may change, as a U.S. District Court mandate allows that in 2005

the state may resume implementing subject matter testing (J. Meyer, personal com-

munication, October 28, 2003).

Candidates in Florida take state-made, multiple-choice and essay tests for their

content areas. The Spanish test assesses candidates’ proficiency in speaking, listen-

ing, writing, and reading, as well as their knowledge of Hispanic cultures (of both

Spain and Spanish America), language structure, and principles of second language

acquisition.

The French test assesses candidates’ communication skills, their knowledge of

French and Francophone cultures, and their knowledge derived from French and

Francophone sources and their connections with other disciplines and information.

In addition, the test evaluates candidates’ knowledge of pedagogy and their knowl-

edge of the nature of language and culture through comparisons of French and their

own language and culture.

The German test references the 1986

Proficiency Guidelines

of the American

Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages to assess candidates’ comprehen-

sion at an advanced level of spoken German passages pertaining to different times

and places on topics of general interest and daily routine and their ability to con-

verse in German at an intermediate-high level, to write German at an

intermediate-high level, and to read at an advanced level a simple connected Ger-

man passage dealing with a variety of basic personal and social needs and topics of

general interest. In addition, the test assesses the examinees’ knowledge of the

following: basic German vocabulary in areas of general interest and application of

vocabulary skills, basic German grammar and syntax in context, the social customs

and daily life of German-speaking countries, the history and geography of Ger-

man-speaking countries, arts and sciences, and pedagogy and professional

knowledge. More information and details about language not mentioned may be

found at <www.fldoe.org/edcert>.

Announcement: Special Series on Assessment xv

Teacher candidates in Texas take the locally developed multiple-choice

Ex-

amination for the Certification of Educators in Texas

(

ExCET

) for certification in

French, German, and Spanish. However, Texas is in the midst of replacing the

ExCET

tests with the

Texas Examination of Educator Standards

(

TExES

), reported

to be based on public school curriculum (State Board for Educator Certification

Information and Support Center, personal communication, October 28, 2003). The

TExES

exams contain five subareas that assess listening, written communication,

language structures, vocabulary and usage, and language and culture. Details about

the

TExES

may be found at <www.texes.nesinc.com>. French and Spanish candi-

dates are also required to take the

Texas Oral Proficiency Test

(

TOPT

), a 75-minute

test in which candidates record their responses to a total of 15 picture, topic, and

situational tasks that range from intermediate to superior levels of proficiency. A

thorough description of each

TOPT

test is available at <www.topt.nesinc.com>.

Given the mobility of contemporary society, readers interested in transferabil-

ity of certification should examine reciprocity agreements established by The

National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification

(NASDTEC). Such information is available at <www.nasdtec.org>.

blank page xvi

11

11

1

No Child Left BehindNo Child Left Behind

No Child Left BehindNo Child Left Behind

No Child Left Behind

in Foreign Language Educationin Foreign Language Education

in Foreign Language Educationin Foreign Language Education

in Foreign Language Education

LL

LL

L

ynne McClendonynne McClendon

ynne McClendonynne McClendon

ynne McClendon

SCOLT Executive Director

AbstractAbstract

AbstractAbstract

Abstract

The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, the revised Elementary

and Secondary Education Act, is one of the most sweeping educational re-

form movements in recent times. While there are many subcomponents of this

Act, one area specifically touches on foreign language education: “highly

qualified teachers.” This article examines the term “highly qualified teacher”

as defined by NCLB, as well as effective practices highly qualified foreign

language teachers, curriculum program specialists, and college of education

instructors can employ to leave no child behind in foreign language educa-

tion. Using this information, teachers, curriculum program specialists, and

college of education instructors can evaluate their own progress and pro-

grams to ensure that all students achieve a level of success in foreign language

studies.

BackgroundBackground

BackgroundBackground

Background

Leaving no child behind implies that

all

students can learn. Over the last de-

cade and a half, foreign language education has been shaped by a guiding “can-do”

philosophy reflected in the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Lan-

guages (ACTFL) Statement of Philosophy in

Standards for Foreign Language

Learning in the 21st Century

:

Language and communication are at the heart of the human experience.

The United States must educate students who are equipped linguistically

and culturally to communicate successfully in a pluralistic American soci-

ety and abroad. This imperative envisions a future in which ALL students

will develop and maintain proficiency in English and at least one other

language, modern or classical. (National Standards in Foreign Language

Education Project, 1999, p. 7)

This same commitment is echoed in the publication

World Languages Other

Than English Standards

(National Board for Professional Teaching Standards,

2001): “Accomplished teachers are dedicated to making knowledge accessible to

all students. They act on the belief that all students can learn” (p. vi).

2

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

States receiving Title I funding must ensure that the teachers of the “core aca-

demic subjects”–English, reading or language arts, mathematics, science,

foreign

languages

, civics and government, economics, arts, history and geography–meet

the definition of “highly qualified” to continue receiving funding (No Child Left

Behind Act of 2001, 2002). The term “highly qualified,” according to the National

Governors Association article, “NCLB: Teacher Quality Legislation,” indicates “that

the teacher has obtained full state certification (including alternative certification)

or passed the state teacher licensing examination, and holds a license to teach in

such state” (2002). The article declares that new elementary teachers, in addition to

having obtained state certification at the minimum of the bachelor’s level, must

also have “passed a test of knowledge and teaching skills in reading, writing, math-

ematics, and other areas of the basic elementary school curriculum.” Likewise new

middle and high school teachers, in addition to holding a valid state certificate at

the bachelor’s level, must also “have demonstrated competency in each of the

teacher’s subjects.”

Regarding veteran teachers, Title IX, section 9101 (23) (C), stipulates that

these teachers must also hold a valid certificate at the bachelor’s level and meet the

same standards required of new teachers by completing course work, passing a

test, or by demonstrating competence in all subject matter taught by the teacher.

The timeline for accomplishing the “highly qualified” teacher status for

all

teach-

ers in the core subjects, including foreign language, is by the end of the 2005-2006

school year. As of 2002-2003, states and local educational agencies must begin

reporting progress toward this goal and ensuring that “new hires” have met the

standards set forth.

Prospective foreign language teachers at the undergraduate levels would do

well to work with their institutions’ departments of education to ensure they have

the appropriate coursework and are prepared as well for teacher tests or other means

of accountability. Beyond the teacher tests, it is important for modern foreign lan-

guage teachers to be fluent enough to use language as a means of instruction in the

classroom. Many colleges and universities offer study-abroad programs designed

to enhance basic language skills obtained in the classroom. As post-secondary de-

partments of education begin aligning their courses of study with the National

Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE)¹ standards and guide-

lines, the prospective foreign language teacher will be on track for successfully

passing tests that may be required by the state as a part of the licensure process and

for performing successfully in the classroom as well.

NCATE was founded in 1954 as a nonprofit and nongovernmental organiza-

tion devoted to the pursuit of ensuring quality teacher education programs through

rigorous standards that the education departments of universities and colleges must

meet in order to become NCATE-accredited. Several educational organizations

and associations comprise the NCATE council and contribute to the ongoing re-

search and refinement of what constitutes effective teacher education programs.

There is an established process for applying for accreditation, with preconditions

for being accepted as a candidate, a program review inclusive of both review of the

portfolio and an on-site review, follow-up reports, and maintenance of accredita-

No Child Left Behind in Foreign Language Education 3

tion once an educational unit has obtained its first accreditation. NCATE also pro-

vides workshops for institutions interested in initiating the process.

What are these standards that NCATE has indicated as the foundations of good

teacher preparation programs, and how were they created? The basic NCATE stan-

dards, developed by teacher educators, practicing teachers, content specialists, and

local and state policy-makers, were based on researched practices and conditions

for learning. Various content-related organizations and groups working with NCATE

took the next step of ensuring usable standards by addressing the core standards in

terms of the particular content area. In this respect ACTFL played an important

role in defining the standards in terms of foreign language education. Using re-

search from the field, the ACTFL Standards Writing Team set forth six content

standards that in general address the following categories: (1) proficiency in the

target language, (2) recognition of the role of culture and incorporating other disci-

plines, (3) language acquisition theories and practices, (4) standards-based

curriculum and implementation of standards in daily lesson plans, (5) the impor-

tance of varied assessments as an integral part of instruction, and (6) the importance

of professional growth for self-improvement with the ultimate goal of providing

the best instruction and classroom environment for all students.

In turn, these six content standards contain subsets of standards, supporting

explanations, and rubrics by which education programs can determine the extent to

which they are preparing future foreign language teachers. The rubric measure

terms (

Approaches Standard, Meets Standard, and Exceeds Standard

) are particu-

larly helpful in determining where program fine-tuning may be needed, and it is

this information that can be particularly instructive to foreign language curriculum

supervisors and practicing foreign language teachers. Since many of the new teachers

will be entering the teaching field with NCATE preparation, the current teaching

field would do well to use these rubrics to self-assess and make determinations

regarding what professional development is needed. Such self-assessments based

on these rubrics could support a curriculum specialist in designing or requesting

funding for professional development opportunities. In this way the foreign lan-

guage classroom becomes a receptive and continuous improvement environment,

edifying for newly certified teachers, current teachers, and most of all, the students.

These six content standards add another dimension to the term “highly qualified”

teachers.

Obviously, “highly qualified” teachers should possess good teaching skills,

but what are “good teaching skills”? A definition of these goals, not a part of the

original bill as it was first introduced in the House, was added to H.R. 2211 (en-

grossed as agreed by the House) “Ready to Teach Act of 2003, Teacher Quality

Enhancement Grants, section 201” to provide some insight into what some legisla-

tors considered to constitute “good teaching skills,” described as follows:

(9) TEACHING SKILLS: The term “teaching skills” means skills that

(A) are based on scientifically based research;

(B) enable teachers to effectively convey and explain subject

matter content;

4

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

(C) lead to increased student academic achievement; and

(D) use strategies that

(i) are specific to subject matter;

(ii) include ongoing assessment of student learning;

(iii) focus on identification and tailoring of academic

instruction to students’s [

sic

] specific learning needs; and

(iv) focus on classroom management.

What models are available for foreign language teachers to evaluate their per-

sonal performance in relation to defining “good teaching”? The National Board

certification process sponsored by the National Board for Professional Teaching

Standards (NBPTS)² presents a wonderful opportunity for teachers, particularly

veteran teachers, to hone their skills and advance student learning. Teachers both

in their portfolio and the one-day assessment center activities are evaluated on 14

standards. The NBPTS publication,

World Languages Other Than English Stan-

dards

(2001), produced by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards,

provides elaboration of these standards and asks prospective candidates to reflect

upon how they are currently meeting these foreign language standards and perhaps

to consider some steps to take to address perceived deficiencies. The following

titles from the table of content represent the 14 standards:

Knowledge of Students, Fairness, Knowledge of Language, Knowledge

of Culture, Knowledge of Language Acquisition, Multiple Paths to Learn-

ing, Articulation of Curriculum and Instruction, Learning Environment,

Instructional Resources, Assessment, Reflection as Professional Growth,

Schools/Families and Communities, Professional Community, and Advo-

cacy for Education in World Languages Other Than English

While some states and local school systems may offer either financial assis-

tance or salary incentives for those undertaking this certification process, teachers

can at least self-assess their own standing regarding the standards presented in this

document whether or not they pursue the certification. Castor (2002) of NBPTS

says, “I routinely heard from participating teachers that the process of seeking this

unique credential was the best form of professional development they had ever

experienced, because it forced them to re-examine and rethink their teaching.” Of

course, many foreign language teachers are already addressing these standards and

would want to pursue obtaining the certification.

These standards, closely related to those found in the NCATE materials, pro-

vide an excellent measure for all foreign language teachers. It should be noted that

among the committee members who developed the standards are past and present

ACTFL Executive Council members as well as other noted foreign language edu-

cators. Many language organizations are offering assistance with the certification

process or facets of the process that will enable teachers to be successful partici-

pants and, of course, “highly qualified.” The NBPTS website² lists the foreign

language teachers who are designated as “National Board Certified Teachers.”

No Child Left Behind in Foreign Language Education 5

Another document,

Model Standards for Licensing Beginning Foreign Lan-

guage Teachers: A Resource for State Dialogue

, produced by the Interstate New

Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC)³ and sponsored by the

Council of Chief State School Officers, addresses similar standards found in the

NCATE and NBPTS documents. Likewise, the INTASC standards exist in many

content areas. The committee charged with developing the INTASC foreign lan-

guage standards correlated the 10 basic INTASC core principles to the performance

expectations for a foreign language teacher. As a result, the following titles repre-

sent the standards for evaluation of effective foreign language teaching:

Content Knowledge, Learner Development, Diversity of Learners, Instruc-

tional Strategies, Learning Environment, Communication, Planning for

Instruction, Assessment, Reflective Practice and Professional Develop-

ment, and Community

Additional information found in the “standards context” provides teachers with

an in-depth understanding of each standard and yet another opportunity to self-

assess.

The purpose of the INTASC document is to provide direction for setting poli-

cies pertaining to licensure, program approval, and professional development of

quality foreign language teachers. While this consortium was created in 1987, the

addition of the foreign language component is as recent as 2001-2002, when the

committee was formed and work was initiated on the foreign language standards.

ACTFL and many of the language specific organizations played a major role in

helping to shape the INTASC foreign language standards in line with research-

based effective practices. Other committee members included practicing teachers

of foreign language education, teacher educators, school leaders, and state educa-

tional agency personnel. As state educational agencies begin to address the issue of

“highly qualified” teachers and ensuring that “no child is left behind,” they will

doubtlessly rely upon this document already supported by state superintendents or

chief school officers. INTASC is already in the process of creating a test that will

assess a beginning teacher’s knowledge of pedagogical practices and a set of per-

formance assessments for new teachers to show that a teacher can design, implement,

and evaluate lessons for diverse learners. Teachers, supervisors of foreign language

teachers, colleges of education, and foreign language organizations would do well

to review these standards as a means of designing activities and programs for help-

ing teachers obtain the “highly qualified” designation.

Finally, for the K-12 teachers who want to focus primarily on instruction and

student evaluation to ensure that they are using the best practices to leave no child

behind, the

ACTFL Performance Guidelines for K-12 Learners

(1998), provide a

barometer for how well students should be performing at the novice, intermediate,

and pre-advanced stages. These guidelines are grounded in the

Standards for For-

eign Language Learning in the 21st Century

(NSFLEP, 1999), which define what

the K-12 foreign language curriculum should look like. Furthermore, these guide-

lines are arranged by modes of communication:

interpersonal

(face-to-face

6

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

communication, as well as personal letters and e-mail),

interpretive

(one-way read-

ing or listening), and

presentational

(one-way writing and speaking). Within these

modes, language descriptors are provided for

comprehensibility

,

comprehension

,

language control

,

vocabulary

,

cultural awareness

, and

communication strategies

.

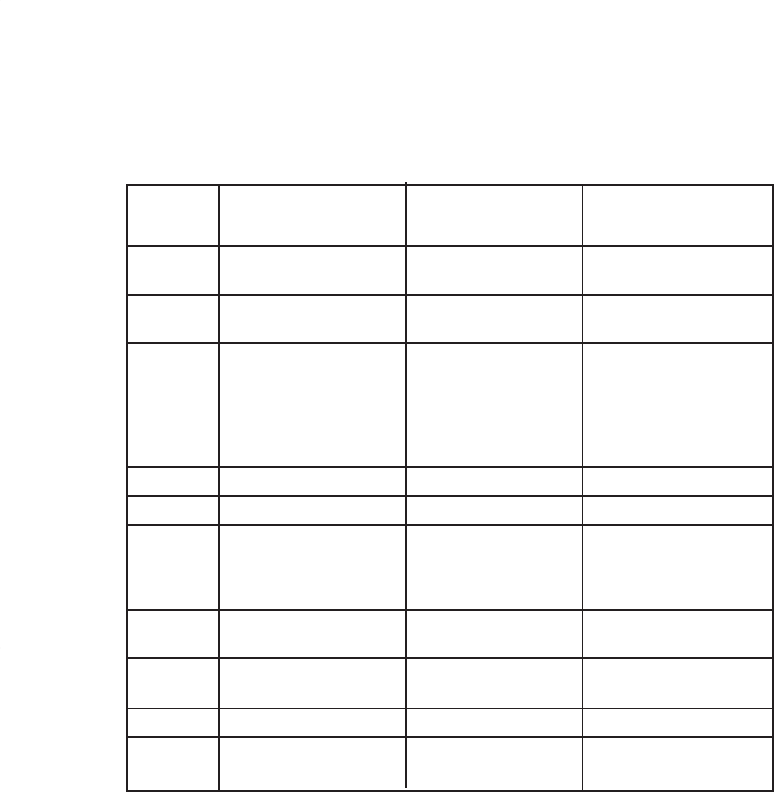

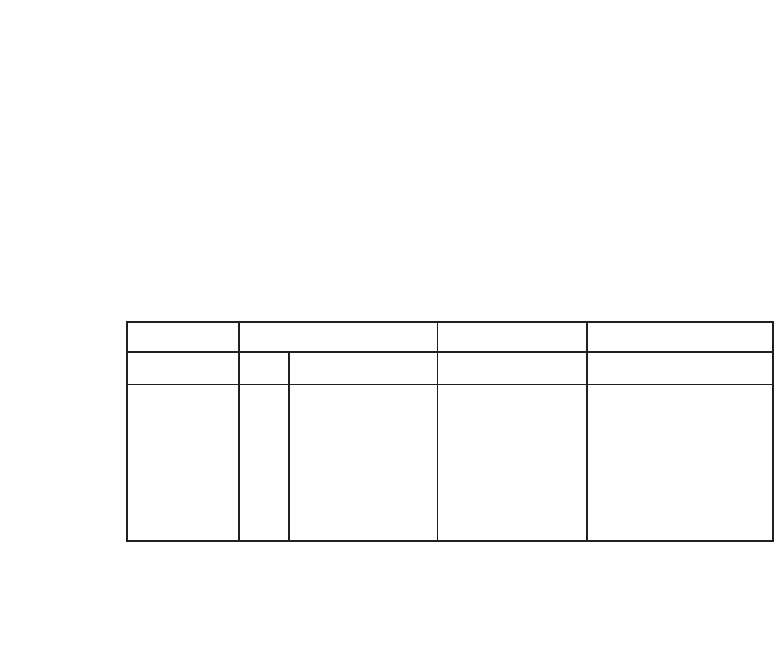

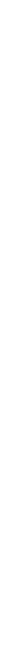

The following example shows the progression of one guideline for “Comprehensi-

bility/Interpersonal” across the three stages.

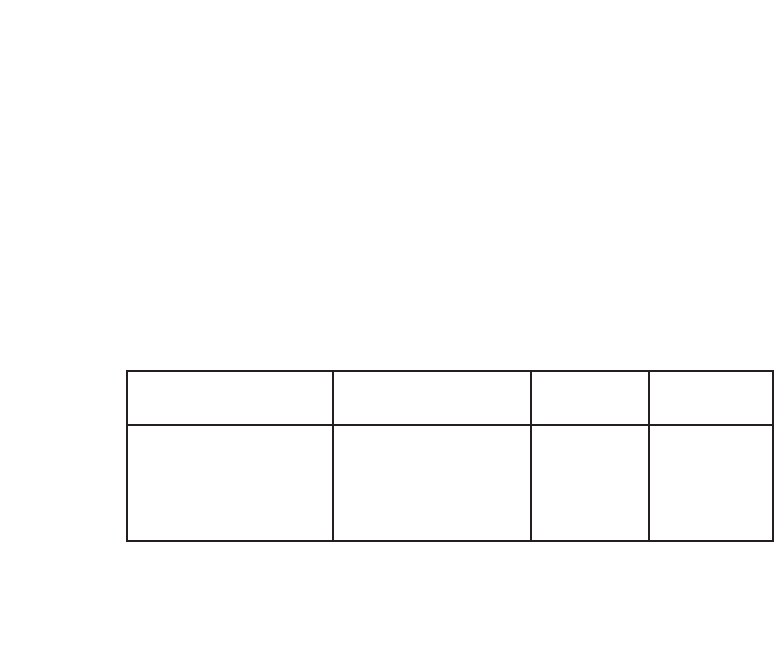

Comprehensibility (How well are they understood?)/ InterpersonalComprehensibility (How well are they understood?)/ Interpersonal

Comprehensibility (How well are they understood?)/ InterpersonalComprehensibility (How well are they understood?)/ Interpersonal

Comprehensibility (How well are they understood?)/ Interpersonal

Reproduced with permission from the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Using the guidelines chart from which the above sample is taken, teachers can

easily identify the stage for a particular group of students and further identify the

number of descriptors their students can satisfactorily complete. By so doing, teach-

ers have the opportunity to plan instruction for the students who are not performing

at the level suggested by the descriptors. The performance chart lists student char-

acteristics and behaviors that can serve as benchmarks for noting student progress

in demonstrating language proficiency. It is also important to note that the Na-

tional Assessment on Educational Progress (NAEP) test in foreign language

(Spanish), scheduled for administration in 2004, uses the following tasks to evalu-

ate student skills: interpretive listening and reading, interpersonal listening and

speaking, and presentational writing.

ConclusionConclusion

ConclusionConclusion

Conclusion

The National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE), speaking

through its recent publication, the

Complete Curriculum: Ensuring a Place for the

Arts and Foreign Languages in America’s Schools

(2003), considers “highly quali-

fied teachers” important enough to list steps to be taken in its first 3 of 10

recommendations to ensure that foreign languages and the arts remain strong and

viable subjects of study. As noted by Tesser and Abbott (2003), a core group of

dedicated foreign language professionals, with input from the wider language and

educational community, has helped to develop consistent themes, measures, ex-

pectations, and philosophical underpinnings to the documents mentioned in this

discussion. The language profession is the better for this unified approach because

Novice LearnersNovice Learners

Novice LearnersNovice Learners

Novice Learners

Rely primarily on

memorized phrases

and short sentences

during highly predict-

able interactions on

very familiar topics ...

Intermediate LearnersIntermediate Learners

Intermediate LearnersIntermediate Learners

Intermediate Learners

Express their own

thoughts using sentences

and strings of sentences

when interacting on

familiar topics in present

time ...

Pre-AdvancedPre-Advanced

Pre-AdvancedPre-Advanced

Pre-Advanced

LearnersLearners

LearnersLearners

Learners

Narrate and describe

using connected

sentences and para-

graphs in present and

other time frames when

interacting on topics of

personal, school and

community interests ...

No Child Left Behind in Foreign Language Education 7

it offers sound research-based and agreed-upon directions for what constitutes for-

eign language teacher quality. The issue of defining a “highly qualified” teacher is

perplexing, and, as Berry (2002) suggests, it will definitely not be productive if

federal guidelines focus primarily on subject matter competence. Nonetheless, the

foreign language profession is indeed very fortunate to have many well-crafted

collaborating models of what goes into making teachers “highly qualified” and, in

the final analysis, what will produce more fluent users of foreign languages.

NotesNotes

NotesNotes

Notes

¹ More detailed information regarding the application process, workshops and

timeline for the first accreditation and standards can be located at the NCATE

Web site: <www.ncate.org>.

² Information on becoming National Board Certified can be obtained at the

NBPTS Web site: <www.nbpts.org>.

³ Information regarding INTASC and for ordering a bound copy of the

Foreign

Language Standards

document can be located at the Web site for the Council

of Chief State School Officers: <www.ccsso.org>.

ReferencesReferences

ReferencesReferences

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). (1998).

ACTFL

performance guidelines for K-12 learners

(with fold-out Assessment Chart).

Yonkers, NY: author.

Berry, B. (October 2002).

What it means to be a “highly qualified teacher.”

South-

east Center for Teacher Quality. Retrieved January 4, 2004, from http://

www.teachingquality.org/resources/pdfs/definingHQ.pdf

Castor, B. (2002). Better assessment for better teaching.

Education Week, 22,

28-30.

National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE). (2003).

The com-

plete curriculum: Ensuring a place for the arts and foreign languages in

America’s schools.

Alexandria, VA: NASBE.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS). (2001).

World lan-

guages other than English standards (for teachers of students ages 3-18+).

Arlington, VA: NBPTS.

National Governors Association. (2002, July 26).

NCLB: Summary of teacher quality

legislation.

Retrieved January 4, 2004, http://www.nga.org/center/divisions/

1,1188,C_ISSUE_Brief^D_4163,00.html

National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project. (1999).

Standards for

foreign language learning in the 21st century

. Yonkers, NY: ACTFL.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Office of Elementary and Secondary Educa-

tion. (2002). (H.R. 1, 107th Cong. (2001), P.L. 107-110). Student Achievement

and School Accountability Conference (October 2002). Slide 12. http://

www.ed.gov/admins/tchrqual/learn/hqt/edlite-slide012.html

8

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

Ready to Teach Act of 2003. (H.R. 2211, 108th Cong. 2003; engrossed). Retrieved

January 4, 2004, from http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?c108:2:./temp/

~c108rd1bvY::

Tesser, C. C., & Abbott, M. (2003). INTASC model foreign language standards for

beginning teacher licensing and development. In C. M. Cherry & L. Bradley

(Eds.),

Dimension 2003: Models for excellence in second language education

(pp. 65-73). Valdosta, GA: Southern Conference on Language Teaching.

Title IX, 9101(23) “Highly qualified [definition]” (C). Elementary and Secondary

Education Act (2002). P.L. 107-110. Retrieved January 4, 2004, http://

www.ed.gov/legislation/ESEA02/pg107.html

22

22

2

Using Learner and Using Learner and

Using Learner and Using Learner and

Using Learner and

TT

TT

T

eacher Preparationeacher Preparation

eacher Preparationeacher Preparation

eacher Preparation

SS

SS

S

tandards to Reform a Language Majortandards to Reform a Language Major

tandards to Reform a Language Majortandards to Reform a Language Major

tandards to Reform a Language Major

Rosalie M. CheathamRosalie M. Cheatham

Rosalie M. CheathamRosalie M. Cheatham

Rosalie M. Cheatham

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

AbstractAbstract

AbstractAbstract

Abstract

While foreign language educators in many university programs have

worked to modify courses to reflect the emerging research on the best

practices for enabling language acquisition by student learners, the overall

curriculum design of language majors remains very similar to structures

in place more than two decades ago. This article describes a series of

initiatives that have led to a major redesign of a French curriculum at a

state university that uses as its organizing principle the two recently de-

veloped professional Standards documents: the Standards for Foreign

Language Learning in the 21st Century (National Standards in Foreign

Language Education Project, 1999) and the ACTFL Program Standards

for the Preparation of Foreign Language Teachers (2002).

BackgroundBackground

BackgroundBackground

Background

For over a decade language department faculty at the University of Arkansas

at Little Rock have been actively engaged in systematic initiatives to establish mean-

ingful assessment of programs and students reflecting the most current professional

research. These efforts have resulted in content revisions in a number of courses in

French, German, and Spanish and in the use of oral proficiency interviews and

written assessment for all language majors immediately prior to graduation as a

measure of program assessment. Since many faculty believe that course grades are

the most accurate reflection of a student’s language ability, a specific level of mas-

tery has not been requisite to graduation. The syllabi of skill courses have changed

substantially over the decades to reflect current understandings of best practices

for language instruction, but the overall curricular structure leading to a major or

minor has remained remarkably similar to that of decades earlier, when neither

proficiency nor standards were bywords of professional language educators.

The current modifications in the French program that have utilized both the

Learner Standards K-16

, ACTFL Standards for Foreign Language Learning in the

21st Century

(National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project, 1999)

and the recently approved Teacher Standards

, ACTFL Program Standards for the

Preparation of Foreign Language Teachers

(2002) as the organizing principle have

resulted in the most significant structural change in the curriculum to date. These

10

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

changes have been specifically designed to assure that all students acquire a more

comprehensive and appropriate command of the target language than was common

in a more traditional program.

The ChallengeThe Challenge

The ChallengeThe Challenge

The Challenge

Both language and pedagogy faculty in the department have been actively

engaged using federal and state-funded grants in advocating to K-12 foreign lan-

guage educators throughout the state the appropriate application of the learner

standards in their programs. There has, however, been little incentive to effect the

changes required to embrace the learner standards in the university curriculum

until the recent approval of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Lan-

guages (ACTFL)/National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE)

Teacher Preparation Standards in October 2002. This new impetus results from the

fact that Arkansas law requires that an institution of higher education be NCATE-

accredited in order for its pre-service teacher candidates to be eligible for licensure.

Failure to attain the requisite levels of proficiency by language teacher candidates

could, therefore, jeopardize the ability of licensure candidates in all disciplines at

the university to obtain teaching credentials. The specific imperative that has led to

the curricular reform described below is to assure that licensure candidates in French

have the maximum opportunity to attain the skill levels required by the approved

Teacher Preparation Standards.

This challenge is exacerbated by two additional realities. One of the require-

ments for teacher candidates to attain the knowledge, skills, and dispositions

described in the

ACTFL Program Standards for the Preparation of Foreign Lan-

guage Teachers

(2002) is “an ongoing assessment of candidates’ oral proficiency

and provision of diagnostic feedback to candidates concerning their progress in

meeting required levels of proficiency” (p. 24). Additionally, “candidates who teach

languages such as French ... must speak at a minimum level of Advanced-Low as

defined in the

ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Speaking

(1999)” (p. 21). While this

level of oral skill is understandably desirable and a reasonable minimum for class-

room teachers, it is a significant pedagogical challenge to university students, as

most of the program’s current graduates begin their study of French at the univer-

sity level. A decade-long effort to provide the highest quality instruction for all

students and recognition of challenges presented by the new Teacher Preparation

Standards are evident in the revised curriculum.

The Early InitiativesThe Early Initiatives

The Early InitiativesThe Early Initiatives

The Early Initiatives

Like their colleagues at many other institutions, faculty at UALR have for

many years attempted to keep abreast of the most current trends and research ini-

tiatives in foreign language pedagogy. Therefore, as proficiency guidelines were

first developed and subsequently codified in the 1986 publication of the

American

Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages/ Interagency Language Roundtable

(ACTFL/ILR) Proficiency Guidelines,

a documented shift began in the lower-level

skill courses toward an attempt to provide instruction that enabled students to com-

Using Standards to Reform a Language Major 11

municate in the target language. Modified Oral Proficiency Interviews (MOPI)

were required in many language skill courses and students in some academic pro-

grams outside the language department were required to attain at least an interview

rating of Intermediate-Mid in order to satisfy degree requirements. Although these

early efforts were somewhat primitive when compared to the expectations and ac-

tivities in modern textbooks and the opportunities for skill enhancement embodied

in various technological applications hardly envisioned at the time, the change

from teaching students about the language to enabling them to communicate in the

language has been embraced for years.

The first substantive curricular change occurred in the mid-1980s, when three

levels of conversation courses were added to the French program. The major was

revised to require all students to complete as a part of their degree requirements at

least one three-semester-hour conversation course at the intermediate or advanced

level as well as a more traditional stipulation for a course in culture and civilization

and at least two courses in literature. The reality, of course, was that apart from the

conversation and culture offerings, the only other content available was in the canon

of literature courses defined either by century or genre. However, the formal shift

to valuing student output of language began at this point.

The next documented institutional effort to update curricular content occurred

in 1992, when the entire language department at UALR became actively engaged

in the Reforming the Major Project, sponsored by the American Association of

Colleges and Universities. Working as a committee of the whole, the foreign lan-

guage faculty determined that the original

ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines

(1986)

should be the organizing principle for skill courses at all levels and, in addition,

that all students should be assessed using the common metric of the proficiency

guidelines. The faculty in each language worked collaboratively to develop an as-

sessment instrument in each language that included testing of speaking, listening,

writing, and reading skills. This assessment was to serve not only as a record of

student skill but also as a measure of the effectiveness of course instruction in

improving each student’s proficiency in each skill. Each student was tracked so

that it would be possible to determine the relative success of students who began

their study of the language at the university level, as measured against those who

had studied over a period of years in K-12 programs or who had studied or lived

abroad.

By chance, the assessment decisions that were a result of the Reforming the

Major Project coincided with the university-wide implementation of a new lan-

guage requirement for students pursuing a bachelor of arts degree. This provision

required students to complete nine semester hours of a language (specifically six

hours at the elementary level and three hours at the intermediate level) or demon-

strate equivalent proficiency. Eager to document to what extent, with what rapidity,

and in which courses student proficiency increased, initial determinations of the

department faculty provided for the newly developed assessment instruments to be

used at three points. The first administration was to be near the completion of the

nine-semester-hour requirement; the second was a course completion component

in the advanced skills sequence required for majors and minors; and finally, the

12

Assessment Practices in Foreign Language Education

same assessment instrument was administered to students immediately prior to gradu-

ation. Although this emphasis on assessment was a well-intentioned effort to

document individual student progress and the effectiveness of course sequencing

in improving proficiency, it soon became evident that the logistics of administering

and grading three assessments per student were a burden, took away from instruc-

tional time, and helped neither the overall language acquisition of the student nor

provided essential data in the determination of the effectiveness of the course work

leading to the major. Performance on the multiple assessments seemed to reflect

student interest and effort to demonstrate proficiency as much as it showed real

progress in knowledge or ability. The faculty decided, then, to administer the lis-

tening, reading, and writing assessment only once, at the end of each student’s

program of study, and to continue the use of the oral proficiency interview.

The Second-YThe Second-Y

The Second-YThe Second-Y

The Second-Y

ear Coursesear Courses

ear Coursesear Courses

ear Courses

When in 1996 the department faculty became a part of the national Language

Mission Project (Maxwell, Johnson, & Sperling, 1999) proficiency-oriented as-

sessment was already requisite for all students majoring in a foreign language, and

the faculty had enough experience to be well aware of the limitations of assessment

instruments to demonstrate course or program quality. The Language Mission Project

provided a new opportunity for department faculty to undertake a collaborative

exploration of the purposes and practices of foreign language teaching and learn-

ing. Since a significant focus of participation in this project was on assuring that

the language curricula reflected the institution’s mission and because the language

requirement after 4 years was fully operational, department faculty determined to

focus on the content of the final “required” course, the third-semester (Intermedi-

ate I) course. This decision was made as faculty recognized that many students

were taking the third-semester course primarily to complete a requirement, whereas

previously most students had enrolled in a third semester either as the first step

toward a major or toward a minor. Where the course had previously served as a

beginning for serious language study, it had become an ending for a large majority

of students.

French faculty made a key decision to substantially alter the course content

from the traditional systematic reentry of structures taught in the elementary course

sequence toward a serious attempt to organize the syllabus around intermediate-

level proficiency guidelines. Believing that students who completed nine semester

hours of language study should be able to “do something” with their language and

knowing that a one-semester intermediate course was “too short” to assure that

students would achieve a sophisticated level of skill mastery, the faculty deter-

mined to organize the course around the intermediate-level speaking and writing

proficiency guidelines, wherein students are expected to be able to survive in the

target culture and to make themselves understood in predictable situations. Tests

and quizzes were minimized, and a series of three projects was implemented, each

of which was designed around real-world activities and focused on both skills and

content that students would need in order to demonstrate culturally appropriate

survival skills.

Using Standards to Reform a Language Major 13

While the exact format of the project emphasis has varied, each relates to

survival. Topics include requirements for a successful study abroad experience, for

working abroad, or for employment with a local company seeking an employee

who can communicate minimally in French. Required activities include having

students present themselves to a potential host family by writing a letter of intro-