"This introduction to the Pauline Letters will take its place among

the most accessible of its kind. Complicated history of exegesis is

presented simply and comprehensibly. Summary boxes in the text

and questions for review and reflection facilitate understanding. A

particular strength is the focus on the theology and ethics of each

letter. A final chapter completes the picture with brief presentations

of the legacy of Paul in the early centuries of the church."

— Carolyn Osiek, RSCJ

Charles Fischer Catholic Professor of New Testament, Emerita

Brite Divinity School

“At last, a responsible and interesting new volume on Paul’s letters

for students! I whole-heartedly recommend it.”

— Clare K. Rothschild

Associate Professor, Scripture Studies

Lewis University, IL

“Daniel Scholz provides us with a very functional text that will work

well for undergraduate or first-year seminary courses in Paul’s let-

ters. The occasion behind each letter is carefully set out, and the

‘Theology’ and ‘Ethics’ sections for each letter will prove helpful. The

graphics within each chapter make it very user-friendly. The ques-

tions at the end of each chapter will allow this to be readily put to

use in academic courses. The final chapter, on such writings as Acts

of Paul and Thecla, Third Corinthians, and Acts of Paul, also provides

a helpful introduction to Paul’s legacy in early Christianity. I heart-

ily recommend this book as a good candidate for courses on Paul’s

letters.”

— Mark Reasoner

Associate professor of theology

Marian University

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 1 2/27/2013 8:37:58 AM

AUTHOR ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I offer my sincere thanks and gratitude to Kathleen Walsh and

Maura Hagarty at Anselm Academic, and especially to Jim Kelhof-

fer, for their enormous editorial contributions that brought this book

to completion. Most importantly, I thank my wife, Bonnie, and our

three children, Raymond, Andrew, and Danielle, for their patience

and support throughout this writing project.

Publisher Acknowledgments

The publisher owes a special debt of gratitude to James A. Kelhoffer,

PhD, who advised throughout this project. Dr. Kelhoffer’s expertise

and passion both as teacher and scholar contributed immeasurably

to this work. Dr. Kelhoffer holds a PhD in New Testament and

Early Christian Literature from the University of Chicago and is

professor of Old and New Testament Exegesis at Uppsala University

in Sweden.

The publisher also wishes to thank the following individual who

reviewed this work in progress:

Jeffrey S. Siker

Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 2 2/27/2013 8:38:11 AM

Introducing the New Testament

Daniel J. Scholz

James A. Kelhoffer, Academic Editor

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 3 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic.

Cover art: Lorrain, Claude (Gellee) (1600–1682). The Embarkation of St. Paul of Rome at

Ostia. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Scala / Art Resource, NY

The scriptural quotations in this book are from the New American Bible, revised edition

© 2010, 1991, 1986, and 1970 by the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc.,

Washington, DC. Used by permission of the copyright owner. All rights reserved. No

part of this work may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from

the copyright owner.

Copyright © 2013 by Daniel J. Scholz. All rights reserved. No part of this book may

be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm

Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN

55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org

Printed in the United States of America

7044

ISBN 978-1-59982-099-6

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 4 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

Introduction: Studying Paul and His Letters 9

PART 1: The Undisputed Pauline Letters

1. Paul of Tarsus 17

Introduction / 17

Understanding and Interpreting Paul / 19

The Life and Letters of Paul / 35

2. First Thessalonians 56

Introduction / 56

Historical Context of 1 Thessalonians / 57

Theology and Ethics of 1 Thessalonians / 68

3. First Corinthians 79

Introduction / 79

Historical Context of 1 Corinthians / 81

Theology and Ethics of 1 Corinthians / 92

4. Second Corinthians 108

Introduction / 108

Historical Context of 2 Corinthians / 109

Theology and Ethics of 2 Corinthians / 120

CONTENTS

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 5 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

5. Galatians 131

Introduction / 131

Historical Context of Galatians / 132

Theology and Ethics of Galatians / 142

6. Romans 156

Introduction / 156

Historical Context of Romans / 157

Theology and Ethics of Romans / 168

7. Philippians 181

Introduction / 181

Historical Context of Philippians / 183

Theology and Ethics of Philippians / 195

8. Philemon 205

Introduction / 205

Historical Context of Philemon / 206

Theology and Ethics of Philemon / 215

PART 2: The Disputed Letters

and Post-Pauline Writings

9. Colossians, Ephesians,

and Second Thessalonians

225

Introduction / 225

Historical Context of Colossians, Ephesians,

and 2 Thessalonians / 227

Theology and Ethics of Colossians, Ephesians,

and 2 Thessalonians / 243

10. First Timothy, Second Timothy, and Titus 255

Introduction / 255

Historical Context of the Pastoral Letters / 256

Theology and Ethics of the Pastoral Letters / 269

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 6 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

11. Later Letters, Narratives,

and the

Apocalypse

of Paul 279

Introduction / 279

The Continuing Legacy of Paul / 280

Overview of the Later Letters, Narratives,

and the Apocalypse of Paul / 292

Index 303

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 7 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 8 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

9

Next to Jesus, no figure has had more influence in Christian tradi-

tion and history than Paul. In fact, studying Paul’s letters is essential

for understanding Christianity. Fortunately, the Christian Scriptures

provide plenty of source material to understand and interpret Paul.

Just as the four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John inform

readers about Jesus, the thirteen Pauline letters in the New Testament

provide information about Paul and his followers. In addition to these

letters, the New Testament Acts of the Apostles also focus on Paul in

its narrative of the early church’s mission and development. Outside

the Christian Scriptures, other letters and narratives contribute to

understanding Paul and his impact in Christian tradition and history.

One of the most important and surprising features of the thir-

teen New Testament letters attributed to Paul is that some of these

letters most likely do not come directly from Paul. Of the thirteen

Pauline letters, scholars are convinced that seven are “undisputed

letters” of Paul. The seven undisputed Pauline letters are Romans,

1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalo-

nians, and Philemon. Written between 50 and 60 CE, these letters

provide direct access to Paul and offer insights into the world of the

first Christians. These seven letters are the primary sources used

today to understand and interpret Paul.

The six others Pauline letters fall into the category of the

“deutero-Pauline letters”: Colossians, Ephesians, 2 Thessalonians,

1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus. Deutero- is a Greek prefix mean-

ing, “second” or “secondary.” These six letters are widely regarded by

scholars as written by followers of Paul sometime between 70 and

Studying Paul

and His Letters

INTRODUCTION

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 9 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

10 THE PAULINE LETTERS

120 CE. For this reason, these letters are often referred to as the

“disputed letters” of Paul.

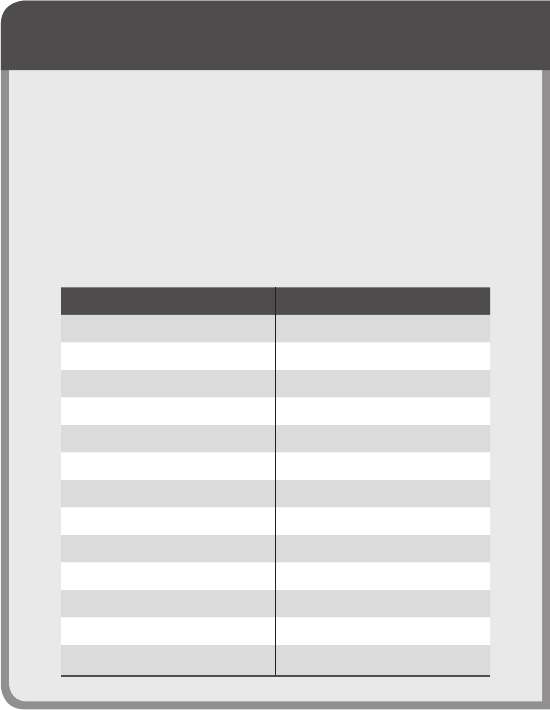

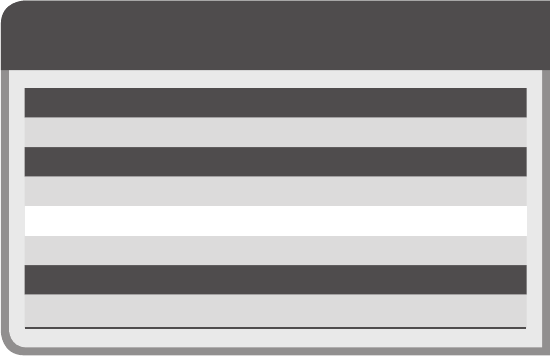

The Letters of Paul in the New Testament

In the New Testament, the thirteen letters attributed to Paul follow

the four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and the Acts of

the Apostles.

The Pauline letters appear in the Bible not in chronological

order but according to length of these letters. Thus, Romans, the

longest of the letters with 7,111 words and 1,687 total verses,

comes first. Philemon, with 335 words and only 25 verses, appears

last in the Bible.

Book Abbreviation

Romans Rom

1 Corinthians 1 Cor

2 Corinthians 2 Cor

Galatians Gal

Ephesians Eph

Philippians Phil

Colossians Col

1 Thessalonians 1 Thess

2 Thessalonians 2 Thess

1 Timothy 1 Tim

2 Timothy 2 Tim

Titus Ti

Philemon Phlm

The Acts of the Apostles is another important source for under-

standing Paul. Written a generation or two after Paul by the same

author who wrote the Gospel of Luke, Acts narrates events from

the ascension of Jesus in Jerusalem to the imprisonment of Paul in

Rome. The author, Luke, commits the entire second half of Acts

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 10 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

Introduction: Studying Paul and His Letters 11

to the missionary activities of Paul. Some of what is known about

Paul from his authentic letters is supported by details from Acts. For

example, the presence of Sosthenes and Crispus in Corinth in Acts

18 parallels references in 1 Corinthians to Sosthenes (1:1) and Cris-

pus (1:14). Other times, however, details from Paul and Acts con-

tradict. For instance, in Galatians 1:18, Paul explains that he waited

three years after his call to go to Jerusalem. However, in Acts 9, Paul’s

visit to Jerusalem appears to occur much more quickly. Needless to

say, these types of disagreements have led scholars to question the

historical reliability of Acts. Given this, most scholars consider Acts

as a secondary source for understanding Paul, as its presentation of

Paul is shaped by Luke’s theology and cannot consistently be cross-

referenced with information from Paul’s letters.

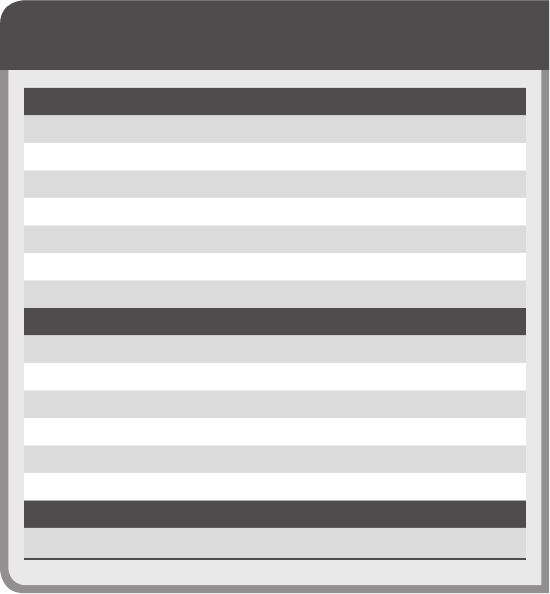

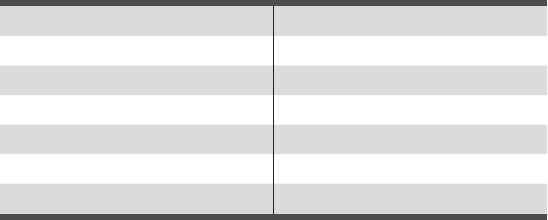

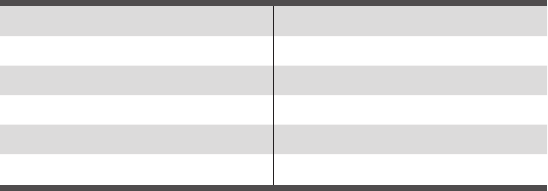

Undisputed Pauline Letters: 50–60 CE

Romans

1 Corinthians

2 Corinthians

Galatians

Philippians

1 Thessalonians

Philemon

Deutero-Pauline Letters: 70–120 CE

Colossians

Ephesians

2 Thessalonians

1 Timothy

2 Timothy

Titus

Narrative: 85–90 CE

Acts of the Apostles

New Testament Sources on Paul

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 11 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

12 THE PAULINE LETTERS

The remaining sources that help us to understand and interpret

Paul fall into the category of extracanonical sources; that is, early

source material not included in the canon of the Christian Scrip-

tures. This source material is classified according to its literary form:

letters, narratives, or apocalypses (end of the age stories). Written

mostly in the second and third centuries CE, these sources highlight

the legacy of Paul centuries after his death.

Narrative: 180–200 CE

Acts of Paul (including Acts of Paul and Thecla)

Letters: 150–300s CE

3 Corinthians

Epistle to the Laodiceans

Correspondence of Paul and Seneca

Apocalypse: 250 CE

Apocalypse of Paul

Extracanonical Sources on Paul

The New Testament sources reveal three important insights

into Paul. First, Paul is complicated. Whether in his early years as a

Jewish Pharisee who was a leader of the persecution of the original

Christians or in his later years, when he challenged Jewish Chris-

tians to accept uncircumcised Gentile Christians as partners in faith,

Paul was no stranger to facing controversy. Further, Paul’s theologi-

cal thinking, as seen in the letters, presents a remarkable integration

of Jewish theology and Greek thought that is not easily understood

today. Second, Paul had an enormous task to accomplish in proclaim-

ing Jesus Christ to the Gentiles. In Paul’s own words, he interpreted

his encounter with the resurrected Christ as a call from God to “pro-

claim [ Jesus] to the Gentiles” (Gal 1:16). In response to this call,

Paul spent the next thirty years spreading the “good news” of Jesus

Christ to Gentiles living in the eastern half of the Roman Empire.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 12 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

Introduction: Studying Paul and His Letters 13

Third, Paul’s theology eventually influenced the course of Christian

history and theology. Within Paul’s lifetime, there were competing

ideas and beliefs about Jesus. Paul’s voice was one among many.

Despite the availability of the various New Testament and

extracanonical sources, Paul remains elusive. However, with the rise

of various scientific methods for studying the sources in the past two

hundred years, theologians and scholars have learned much about

how to better understand and interpret Paul and his letters. The

Pauline Letters presents the fruits of this labor and addresses some

of the context and background information needed for an informed

understanding of Paul and his letters.

Chapter 1, “Paul of Tarsus,” begins with a brief history of the

modern interpretation of Paul. This chapter includes the criteria and

sources used in this book for interpreting Paul as well as the first-

century Jewish and Hellenistic contexts on him. The second half of

the chapter summarizes what scholars know about the life of Paul

and presents an overview of his letters and of ancient letter writing.

Chapter 1 lays the foundation for the two main parts of this

book—part 1: the seven undisputed Pauline letters, and part 2: the

disputed letters and post-Pauline writings. Part 1 consists of chap-

ters 2–8 and takes up the seven undisputed letters of Paul. Although

scholars debate about the dates and order of composition of the let-

ters, part 1 of this book proceeds with the following hypothetical

dates and order:

1 Thessalonians 50 CE

1 Corinthians Spring 55 CE

2 Corinthians Fall 55 CE

Galatians Late 55 CE

Romans Spring 56 CE

Philippians 60 CE

Philemon Late 60 CE

These chapters focus on the historical, social, and literary con-

texts of each letter as well as what these letters reveal about Paul’s

theology and ethics.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 13 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

14 THE PAULINE LETTERS

Part 2 begins by examining the six remaining letters attrib-

uted to Paul—but disputed by scholars—in the New Testament.

Although scholars debate the dates and order of composition of

these letters also, part 2 of this book proceeds with the following

hypothetical dates:

Colossians 70–100 CE

Ephesians 80–110 CE

2 Thessalonians 90–100 CE

1 Timothy 100 CE

2 Timothy 100 CE

Titus 100 CE

Chapter 9 focuses on the deutero-Pauline (or disputed) letters

of Colossians, Ephesians, and 2 Thessalonians; and chapter 10 con-

siders the disputed letters of 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus, also

known as the Pastoral Letters. These chapters discuss the develop-

ing historical, social, and literary contexts in which the letters were

written as well as the theology and ethics of each letter. Chapter11

provides a historical and theological overview of certain later letters,

narratives, and an apocalypse that claim to convey traditions about

Paul. Knowledge of these extracanonical sources is important for

understanding the legacy of Paul in the second and third centuries.

Studying Paul and his letters will provide readers with much

information and plenty of insights into Paul. The abundance of

sources on Paul, canonical and extracanonical, will shed light on

the obstacles and opportunities that the earliest Christians faced in

spreading their versions of the good news of Jesus Christ throughout

the Roman Empire.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 14 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

The Undisputed

Pauline Letters

PART 1

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 15 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 16 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

17

Paul of Tarsus

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter examines the historical figure of Paul of Tarsus. The

beginning of the chapter includes a brief survey of modern attempts

to interpret Paul as well as the interpretative criteria to be used in

this book. It also includes some details of the canonical and extra-

canonical sources available for understanding Paul as well as the

first-century Jewish and Hellenistic influences that shaped his life

and work. The latter part presents a summary overview of Paul’s life

and some background information on his letters.

The Reception of Paul

in Christian History and Theology

The reception of Paul and his letters in the formation of the New

Testament and throughout Christian history can hardly be over-

stated. Nearly half of the New Testament writings are attributed

to him: thirteen of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament

are traditionally associated with Paul, and his legacy stretches well

beyond them. Leading figures from every period of church history

have wrestled with the person of Paul and his theological thinking.

From the writings of church fathers (such as Augustine of Hippo)

to the theology of the sixteenth-century Reformers (such as Martin

Luther) to the rise of the modern historical criticism (for example,

F. C. Baur and Ernst Troeltsch) and the “new perspective” on Paul

(such as E. P. Sanders), scholars have responded to the theology and

person of Paul as reflected in his surviving letters.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 17 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

18 THE PAULINE LETTERS

A Biblical Figure like No Other

Unlike any other figure in the New Testament, Paul can be known in

a unique and distinctive way—through the seven letters that schol-

ars are confident he wrote. Within the context of modern historical

criticism of the Bible, such a claim can be said of no one else in the

New Testament, including Jesus. To be sure, the four New Testament

Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John provide information

about Jesus, but these are his words and deeds as preserved, recorded,

and edited by later Gospel writers a generation removed from the

actual events. Jesus himself left no written account of his words,

thoughts, and deeds. This is true of Peter as well, another leading

figure in the New Testament. The two letters attributed to Peter

in the New Testament (1 Peter and 2 Peter) are, in fact, written by

others in his name one or two generations after his death.

Paul’s seven undisputed letters offer insights into his theology

and the world of the early Christians. Through the lens of Paul’s

perspective, contemporary readers can see the hopes and the chal-

lenges of some of the original Christians who formed communi-

ties around their belief in Jesus as the Messiah and Son of God.

In addition, the letters also show some of the earliest theological

thinking to emerge in light of the Christians’ belief in the death and

Resurrection of Jesus.

The Limits of Historical Inquiry

Despite the advantage and opportunity these letters offer for under-

standing both Paul of Tarsus and the Christians he associated with,

they carry some limitations. Although Paul’s actual missionary out-

reach to the Gentiles spanned nearly thirty years, from about 35 to

64 CE, the seven undisputed Pauline letters cover only a portion of

those years, approximately 50 to 60 CE. If Paul wrote at all in the

first half of his thirty-year missionary work, no letters have been

discovered to date. Neither is there any record of undisputed letters

dating to Paul’s final years. Furthermore, the “occasional” nature of

Paul’s letters limits their usefulness. By occasional, scholars mean that

Paul wrote to address specific situations—the particular problems

and concerns of certain congregations. Paul’s surviving letters never

give a systematic summary of his theology. Indeed, he may be best

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 18 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

Paul of Tarsus 19

understood as a pastoral theologian, applying the gospel to the

changing situations he faced.

UNDERSTANDING

AND INTERPRETING PAUL

To understand and interpret Paul today requires a brief overview of

the past two centuries of Pauline research. This section examines

the established paradigms and perspectives that have shaped con-

temporary approaches to Paul. It also discusses the main sources for

Paul, both canonical and extracanonical, that have informed these

paradigms and perspectives. The section concludes with a closer look

at some of the first-century Jewish and Hellenistic influences that

shaped Paul.

Brief History of Modern Interpretation

The work of Pauline scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centu-

ries finds it roots in the sixteenth-century Reformation period as well

as the eighteenth-century Age of Enlightenment and Age of Reason

that influenced the Western cultures of Europe and America. In his

approach to the study of the Bible from a linguistic and historical

perspective, sixteenth-century Reformer Martin Luther ignited some

of the earliest studies of Jesus, Paul, and the early Christian commu-

nities. The work of Luther and other reformers laid the foundation

for later biblical studies. In the eighteenth century, fundamental ideas

and concepts in areas such as science, art, history, music, philosophy,

and religion were being thought about in new and different ways.

The Bible itself was not immune to these changes in thinking.

Scholars began examining the Old and the New Testaments anew

in terms of their literary, historical, and cultural dimensions. In short,

human reason was now being applied to the study of the Bible. This

new Western perception of reality even affected the understanding of

the New Testament’s central figures, Jesus and Paul.

Much of the discussion on Paul in the past two hundred years

has centered upon the question of Paul’s relationship to the Judaism

of his day. Connecting Paul to Judaism dates back to the nineteenth

century and the foundational studies generated by the early work of

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 19 2/27/2013 8:38:21 AM

20 THE PAULINE LETTERS

historical-critical scholarship. The research and writing of leading

German scholars such as F. C. Baur (1792–1860), Paul, the Apostle

of Jesus Christ (1845); Ferdinand Weber (1812–1860), The Theologi-

cal System of the Ancient Palestinian Synagogue Based on the Targum,

Midrash and Talmud (1880); Emil Schürer (1844–1910), The History

of the Jewish People in the Age of Christ (1897); and Wilhelm Bousset

(1865–1903), The Judaic Religion in the New Testament Era (1903),

paint a portrait of ancient Judaism that shaped early interpretations

of Paul.

1. For a good resource on Pauline terminology (e.g., salvation, righteousness, etc.),

see Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid, eds. Dictionary of Paul

and His Letters: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove,

IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993).

Understanding the vocabulary that Paul uses in his letters can be

one of the more vexing problems that people encounter in trying

to interpret Paul. The following list notes some common terms Paul

used along with a general definition of each term and one or more

passages in which the term appears.

Faith (Greek: pistis)—an absolute trust, belief in God

●

Galatians 3:7—“Realize then that it is those who have faith

who are children of Abraham.”

Gospel (Greek: euaggelion)—good news, glad tidings. For Paul, it

was a term that encompassed God’s saving work in Jesus Christ.

●

Romans 1:16—“For I am not ashamed of the gospel. It is the

power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes; for

Jew first, and then Greek.”

Grace (Greek: charis)—favor, often divine favor freely given.

●

2 Corinthians 6:1—“Working together, then, we appeal to you

not to receive the grace of God in vain.”

Continued

Pauline Terminology

1

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 20 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 21

Pauline Terminology Continued

Justice/Righteousness (Greek: dikaiosynē)—what God required. For

Paul, it is God’s restoration of humanity through Jesus Christ. Paul

often uses this term in its derivation, justification and interchange-

ably as righteousness.

●

Galatians 2:21—“I do not nullify the grace of God; for if justifi-

cation comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing.”

●

Romans 3:21–22—“[T]he righteousness of God has been mani-

fested apart from the law . . . through faith in Jesus Christ.”

Law (Greek: nomos)—law; God’s instructions to Israel for proper rela-

tionship with God and others. The Mosaic Law, which prescribed

the Jewish way of life, was defined in both oral and written form.

●

Romans 7:25—“Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our

Lord. Therefore, I myself, with my mind, serve the law of God

but, with my flesh, the law of sin.”

Salvation (Greek: sōtēria)—the result of God’s action in Jesus Christ,

awaiting final fulfillment in God’s coming kingdom.

●

1 Thessalonians 5:9—“For God did not destine us for wrath,

but to gain salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Sanctification (Greek: haiasmos)—a process of becoming holy

because of faith in Christ.

●

Romans 6:22—“But now that you have . . . become slaves of

God, the benefit that you have leads to sanctification, and its

end is eternal life.”

Sin (Greek: hamartia)—An offense against God, literally meaning,

“to miss the mark.”

●

1 Corinthians 15:3—“For I handed on to you as of first

importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins

in accordance with the scriptures.”

These publications portrayed the Judaism of Paul’s day in very

negative terms—a narrow and legalistic system based on a rigid set

of Torah-based demands that led to self-reliance on one’s own works

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 21 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

22 THE PAULINE LETTERS

for salvation. The so-called late Judaism was seen to have undergone

devolution from the lofty morals of the later Israelite prophets to the

(supposedly) legalistic Pharisees. Rather than cultivating the human-

divine relationship, it was argued, these religious structures prohib-

ited direct access between God and the Israelites. Such a pejorative

view of ancient Judaism provided the lens through which Paul was

understood and interpreted. The research of these Christian scholars

led to the conclusion that Paul became an “outsider” to his Jewish

religion, even an anti-Jewish outsider. Paul had, in fact, become a

“Christian,” who offered to the world an alternative to the Jewish

way and a restoration of the ideals of ancient Israelite religion that

had become corrupted in the centuries before Jesus’ birth. As the

great (Christian) apostle to the Gentiles, Paul brought the Christian

God revealed by Jesus to the non-Jewish world of the first century.

Nineteenth-century New Testament scholarship was convinced that

Paul fought the Judaism of his day by advocating that through Christ

God was once again made accessible. Paul’s emphasis that salvation

was achieved not by works of the Mosaic Law but by faith in Christ

became the great dividing line that showed Christianity’s superiority

over Judaism. Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) solidified this tradi-

tional view of both Paul and Judaism by the mid-twentieth century.

2

In the late 1940s, Bultmann wrote two books that significantly

contributed to standardizing the nineteenth-century negative assess-

ment of the ancient Judaism of Paul’s day: The Theology of the New

Testament (1948) and Primitive Christianity in Its Historical Setting

(1949).

3

Bultmann saw justification by faith as the center of Paul’s

2. The emphasis on Paul’s center of thought grounded in “justification by faith” by

nineteenth- and twentieth-century German (Protestant) Pauline scholars originated

in the work of the sixteenth-century Reformer Martin Luther.

3. See Rudolf Karl Bultmann, Theologie des Neuen Testaments (Tübingen: Mohr,

1948); ET: Theology of the New Testament, trans. Kendrick Grobel. (New York: Scrib-

ner, 1951) and Das Urchristentum im Rahmen der antiken Religionen (Zürich: Artemis,

1949); ET: Primitive Christianity in Its Historical Setting, trans. R. H. Fuller. (Philadel-

phia: Fortress Press, 1980). In one of Bultmann’s earliest and most influential publica-

tions, The History of the Synoptic Tradition (1921), Bultmann employed a form-critical

study of the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Bultmann’s research

established the framework from which the activities of the early church and the

formation of the oral and written gospel tradition would shape the training and

education of students of biblical studies for generations.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 22 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 23

thought. In his view, this Pauline doctrine was the linchpin that

held together Paul’s theology and best represented Paul’s fundamen-

tal break from Judaism. According to Bultmann, ancient Judaism

mistakenly understood justification as achieved through one’s own

merit, through one’s work of the law. Paul contrasts this erroneous

view of self-justification with justification by faith alone. Justifica-

tion that leads to salvation cannot be merit-based; it is achieved

only through faith in Jesus Christ. Faith in Christ is a gift, a grace

bestowed by God.

This characterization of the split between ancient Judaism and

Paul on the question of justification found support well into the sec-

ond half of the twentieth century. Until the 1980s, almost all Pauline

scholars held this view.

4

The Legacy of Paul

The life and letters of Paul created a legacy early on in Christian-

ity. Evidence of this legacy can already be seen within the canon of

the New Testament. Embedded within the Second Letter of Peter,

dated by many scholars to the early second century CE, is a refer-

ence to Paul and his letters: 2 Peter 3:15–16. The author speaks of

the wisdom given to Paul for his letter writing, as well as that in

Paul’s letters there are “some things hard to understand” and cer-

tain people “distort to their own destruction.”

The publication of E. P. Sanders’s 1977 book, Paul and Palestin-

ian Judaism, marked a significant breakthrough in Pauline scholar-

ship. Sanders successfully challenged the now centuries-old negative

view of ancient Judaism as a narrow, legalistic religion centered on

4. Two of Bultmann’s leading students, Ernst Käsemann (1906–1998) and Gün-

ther Bornkamm (1905–1990), held this view. In 1969, both scholars published influ-

ential books on Paul: Käsemann, Perspectives on Paul (Philadelphia: Fortress Press),

and Bornkamm, Paul (Philadelphia: Fortress Press). Each perpetuated Bultmann’s and

other scholars’ negative view of ancient Judaism and carried on the argument of justi-

fication by faith as the center of Paul’s thought and the lens through which to view the

split between Paul and the Judaism of his day.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 23 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

24 THE PAULINE LETTERS

self-justification achieved through works of the law.

5

His research

of Palestinian Jewish literature facilitated a monumental shift in the

discussion of ancient Judaism. In this literature, dated 200 BCE to

200 CE, Sanders noticed a “pattern of religion” within Palestinian

Judaism and argued that the Judaism of Paul’s day was actually a

religion of “covenantal nomism.”

In speaking of covenantal nomism, Sanders argued that Pauline

scholarship had gotten it wrong by characterizing ancient Palestinian

Judaism as a legalistic “works-righteousness” religion. Salvation was

not something achieved by one’s work through adherence to the law;

rather, salvation was a grace, a gift from God established through the

covenant with Israel. Justification was an act of divine grace. The law

(nomos in Greek), or Torah, served as a means to remain (and return)

to the right relationship with God as specified in the covenant.

Knowing that all people sin and fall short of the covenant, ancient

Palestinian Jews viewed observing the law as their covenantal obliga-

tion and as the means by which they can remain in right relationship

with God. Justification or righteousness (from the same Greek word,

dikaiosynē) could not be earned by one’s merit; it was a gift to all Jews

who desired to be in the covenant.

Sanders’s argument that ancient Palestinian Judaism is better

understood through the lens of covenantal nomism made such an

impact in the field of Pauline scholarship that this approach came

to be called the new perspective on Paul.

6

It offered a new genera-

tion of scholars an opportunity to see Paul and his relationship to the

5. For other instances, especially in the twentieth-century Pauline scholarship, in

which the standard view of Paul and his relationship to ancient Judaism has been

challenged: see Magnus Zetterholm, Approaches to Paul: A Student’s Guide to Recent

Scholarship (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2009), 90–93. Zetterholm discusses the work

of three scholars in particular who challenged the research and conclusions of oth-

ers who studied Paul in relation to rabbinic Judaism and rabbinic literature: Salomon

Schechter, Aspects of Rabbinic Theology (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1909);

Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore, Judaism and Saint Paul: Two Essays (London:

Goshen, 1914); George Foot Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” Harvard Theo-

logical Review 14 (1921): 197–254. In fact, as Zetterholm points out, much of Sanders’s

research is built upon the earlier critiques of Montefiore and Moore, 100–105, and

more recently, Krister Stendahl, 97–102.

6. James D. G. Dunn is credited with coining the phrase “new perspective” in his

1982 lecture at the University of Manchester and subsequent publication, “The New

Perspective of Paul,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 65

(1983): 95–122. See also Krister Stendahl, Paul Among Jews and Gentiles (Philadelphia:

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 24 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 25

Judaism of his day in a different light. Scholars of the new perspective

such as N. T. Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said (1997), and Paul: In

Fresh Perspective (2005), and James D. G. Dunn, The Theology of Paul

the Apostle (1998) no longer held the traditional view that Christian-

ity was the religion of grace in opposition to the works-righteousness

religion of Judaism. Sanders, Wright, Dunn, and other new-perspec-

tive scholars do not view Paul as anti-Jewish or as a religious reformer

outside the Judaism of his day. Rather, they see Paul within the Judaism

of his day, recognizing how a judgment of ancient Judaism as simply a

legalistic “works-righteousness” religion unfairly distorts the Judaism

that Paul and other believers in Jesus encountered and engaged.

This most recent generation of Pauline scholarship has given

birth to “the radical new perspectives of Paul,” which holds such

positions that for Paul there were two covenants, one for Jews and

one for Gentiles.

7

This most recent development in the reorienta-

tion of Paul to the Judaism of his day has created tension between

the new perspective and the radical new perspective. The latter

contends that the new perspective simply repeats the old paradigm,

albeit in a new and creative way. The former argues that the radi-

cal new perspective too narrowly limits Paul to the Judaism of his

day. Regardless of these varying positions, the reorientation of Paul

has launched research and publication in areas such as Paul and the

Roman Empire and Paul and economics.

8

These latest approaches to

Fortress Press, 1976), 78–96, and his essay “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective

Conscience of the West,” Harvard Theological Review, 56 (1963): 199–215, in which

he argues twentieth-century perspectives, such as guilty conscience, are routinely

and wrongly projected onto first-century Paul. These insights also helped shape the

“new perspective.”

7. See Zetterholm, chapter 5, “Beyond the New Perspective,” 127–164, for a sam-

pling of studies on this radical new perspective on Paul. See also the panel discussion

“Newer Perspectives on Paul” at the 2004 Central States Society of Biblical Litera-

ture in Saint Louis. See Mark D. Givens, ed., Paul Unbound: Other Perspectives on the

Apostle (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2010): 1. See also John G. Gager, Reinventing

Paul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), who offers an overview of the tradi-

tional and newer perspectives on Paul.

8. On Paul and the Roman Empire, see Neil Elliott, The Arrogance of Nations:

Reading Romans in the Shadow of the Empire (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2008); on

Paul and economics, see David J. Downs, The Offering of the Gentiles: Paul’s Collection

for Jerusalem in Its Chronological, Cultural and Cultic Contexts (2008); and on Paul and

women, see Jorrun Økland, Women in Their Place: Paul and the Corinthian Discourse of

Gender and Sanctuary Space (London: T & T Clark, 2004).

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 25 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

26 THE PAULINE LETTERS

Paul illustrate well the contemporary trends in Pauline scholarship

and the potential for future areas of exploration that have been facili-

tated by this new perspective on Paul in recent decades. These trends

also illustrate the impact of post-Holocaust interpretation on biblical

studies, as Christian scholars have sought to find salvific room for

Jews apart from Christ.

Pauline Christianity

Among the first generation of believers in Jesus as the Mes-

siah and Son of God, Paul’s voice was one among many. These

voices offered diverse and competing ideas about Jesus. Paul’s

own insight into Jesus, which he wrote was “not of human ori-

gin . . . it came through a revelation of Jesus Christ” (Gal 1:11–12),

was one of the distinguishing characteristics of his gospel and

“Pauline Christianity.”

Paul employed a variety of strategies to deal with these dif-

ferent ideas about Jesus. Sometimes Paul reacted angrily to these

other voices, as when he heard that another gospel was sway-

ing the Gentile churches of Galatia: “O stupid Galatians! Who has

bewitched you?” (Gal 3:1). At other times, Paul countered by pre-

senting a more detailed account of his gospel, as when he wrote

his letter to the Romans, introducing himself and his gospel to the

Christians in the city of Rome whom he had yet to meet.

Criteria for Interpreting Paul

Regardless of whether scholars begin with the assumption that Paul

was a convert outside the Judaism of his day or a reformer who

remained within Judaism, all approaches to Paul embrace a set of

criteria, either clearly stated or simply assumed. The set of criteria, in

turn, then shapes the interpretative process. This book is no excep-

tion, employing its own criteria for interpreting Paul and his letters.

The first criterion used here has to do with the sources on Paul.

Not all receive equal treatment; that is to say, some are considered

more important primary sources, while others are considered less

reliable. The primary sources, the seven undisputed Pauline letters,

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 26 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 27

provide the best information for understanding and interpreting

Paul. Additional sources—the remaining six New Testament let-

ters attributed to Paul, the Acts of the Apostles, and extracanonical

material (such as early church writings, archeological materials, and

so on)—contribute to the interpretation of Paul. These other sources

must be understood within the context of their place and time in the

development of the early church and Pauline Christianity.

The handling of the sources leads to this book’s second criterion.

Because the letters of Paul are occasional letters, the information and

details contained in each should be explored in light of its specific

historical setting, theology, and ethics (that is, rules of conduct).

Each Pauline letter must be allowed to stand on its own because each

was written for a particular occasion. Further, sorting through the

theology and ethics embedded in these letters requires close scru-

tiny. Some of Paul’s thinking forms the basis of his larger theological

framework (for example, justification by faith in Christ: Gal 2:15–12;

Rom 3:21–28; Phil 3:7–11); some is very situational (such as the case

of incest in Corinth, 1 Cor 5:1–13); and some belongs to a received

tradition he inherited (for instance, the celebration of the Eucharist

in Corinth, 1 Cor 11:23–26).

The occasional nature of Paul’s letters, criterion two, connects

directly to the third criterion: the chronological treatment of Paul

and his letters. The history, theology, and ethics within Paul’s letters is

commonly handled either thematically or chronologically. Although

both approaches have merit, this book proceeds with a chronological

treatment, which reinforces the idea that these occasional letters are

best understood within the chronology of Paul’s life, the evolution of

his own theological thinking, and the historical developments within

the first and second generation of Christians.

9

Sources on Paul

Scholars categorize the source material on Paul in a variety of ways.

The clearest division is between canonical sources (those within the

9. This chronological approach is advocated by some of the best contemporary

treatments of Paul. See Udo Schnelle, Apostle Paul: His Life and Theology, trans. M.

Eugene Boring (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2003). For a good example of

a thematic approach to Paul, see James D. G. Dunn, The Theology of Paul the Apostle

(Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 1998).

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 27 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

28 THE PAULINE LETTERS

New Testament) and extracanonical sources (those outside the New

Testament). Source material on Paul (and Pauline Christianity) within

the canon of the New Testament is plentiful, with the most important

source material in the canon being the seven undisputed letters of Paul.

First Thessalonians, the earliest of the seven, was written from the city

of Corinth in 50 CE, sometime after Paul was expelled from the city

of Thessalonica. Paul probably wrote 1Corinthians in the spring of

55 CE and his Second Letter to the Corinthians in the fall of 55 CE,

possibly from the city of Ephesus. Shortly after 2 Corinthians, Paul

wrote his Letter to the Galatians. Probably a year or two later, Paul

wrote his Letter to the Romans in the spring of 56 CE. During one

of his imprisonments (possibly in Ephesus, Caesarea, or Rome), Paul

composed his Letter to the Philippians and his Letter to Philemon.

Pseudepigraphy

Pseudepigraphy, from the Greek pseudēs, ”false,“ and epigraphē,

”inscription,” is the act of writing in another’s name. A common

practice in the ancient world, pseudepigraphy was an attempt to

deceive the recipients of the written work. An example of pseud-

epigraphy would include the first century CE ”Letters of Socrates“

which are presented as if Socrates (470–399 BCE) had written them.

Old Testament pseudepigrapha were quite popular between

the years 200 BCE and 200 CE. Many Jewish writings were attributed

to biblical characters such as Adam and Eve (Life of Adam and Eve),

Moses (Assumption of Moses) and Isaiah (Martyrdom and Ascension

of Isaiah). Early Christians carried on the tradition of pseudepigra-

phy in works such as the Gospel of Peter (mid-second century CE)

and Paul’s Epistle to the Laodiceans (mid-third century CE).

Most scholars acknowledge the likelihood of pseudepigraphic

works in the New Testament. For example, the apostle Peter, mar-

tyred in the mid-60s CE, did not write the First and Second Letter

of Peter, composed in the late first century and early second cen-

tury CE, respectively. In the case of Paul’s letters, the majority of

scholars believe that later Pauline Christians writing in Paul’s name

composed the Pastoral Letters (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus) and

Ephesians. Scholars are less certain if this is the case with Colossians

and 2 Thessalonians.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 28 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 29

The remaining source material on Paul in the New Testament

consists of the six deutero-Pauline letters of Colossians, Ephesians,

2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus, and the Acts

of the Apostles.

10

Paul did not write the six remaining Pauline let-

ters. Scholars speculate that the real authors may have been either

close associates of Paul during his lifetime or contemporary leaders

within the Pauline communities that survived after his death. These

unknown authors were attempting to carry on the theology and eth-

ics of Paul, adapting it to their new circumstances. Scholars debate

the exact date and place of composition of these letters. They were

likely written between the years 70 and 120 CE. There also appears

to be some literary relationship among these Pauline letters; for

example, Ephesians is a later expansion of Colossians. As a whole,

these letters take up the concerns of the second and third generations

of Pauline Christianity and reflect the legacy of Paul’s influence in

the early church.

An additional New Testament source for understanding and

interpreting Paul is the Acts of the Apostles. Composed in the late

first century CE by the same author who wrote the Gospel of Luke,

this two-part narrative, Luke-Acts, tells the story of Christianity

from the birth and infancy of Jesus (Luke 1–2) to Paul’s imprison-

ment in Rome (Acts 28). Luke offers his perspective on Paul only

decades removed from the actual historical events. Much of what

Luke relates about Paul in the Acts of the Apostles can be verified

from the authentic Pauline letters.

Source material on Paul (and Pauline Christianity) outside

the New Testament is scarce. Scholars classify much of this source

material as “apocryphal Pauline literature.” Apocryphal here refers to

early Christian writings not included in the New Testament. This

source material includes letters, acts, and apocalypses (end of the

age stories) that were written in Paul’s name or about Paul, mostly

from the second through the fourth century CE. These pseude-

pigraphic works include extracanonical letters (3 Corinthians, the

Epistle to the Laodiceans, and the Correspondences between Paul and

Seneca), an extracanonical narrative (the Acts of Paul, which includes

the Acts of Paul and Thecla), and an extracanonical apocalypse

10. Jude, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter could be included here on the list, as many scholars

regard these New Testament letters as additional post-Pauline trajectories.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 29 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

30 THE PAULINE LETTERS

(Apocalypse of Paul).

11

More so than actually disclosing information

about Paul, this source material shows how the early church used

Paul and his theology to address the concerns, debates, and issues of

their times.

Pauline Contexts: Jewish and Hellenistic

Modern approaches to Paul rightly consider both the Jewish and

Hellenistic contexts that shaped his life and his worldview. Paul

was ethnically a Jew (a Hebrew) of the tribe of Benjamin (Phil 3:5),

born and raised in the Greek city of Tarsus in Cilicia (Acts 21:39), a

region several hundred miles north of Jerusalem, outside of Palestine.

Luke also presents Paul as a Roman citizen (Acts 22:22–29). Further,

Paul and his fellow first-century CE Jews lived in a period of history

heavily influenced by Hellenism—defined as the adoption of Greek

language, literature, social customs, and ethical values. Both Judaism

and Hellenism formed and informed Paul throughout his life.

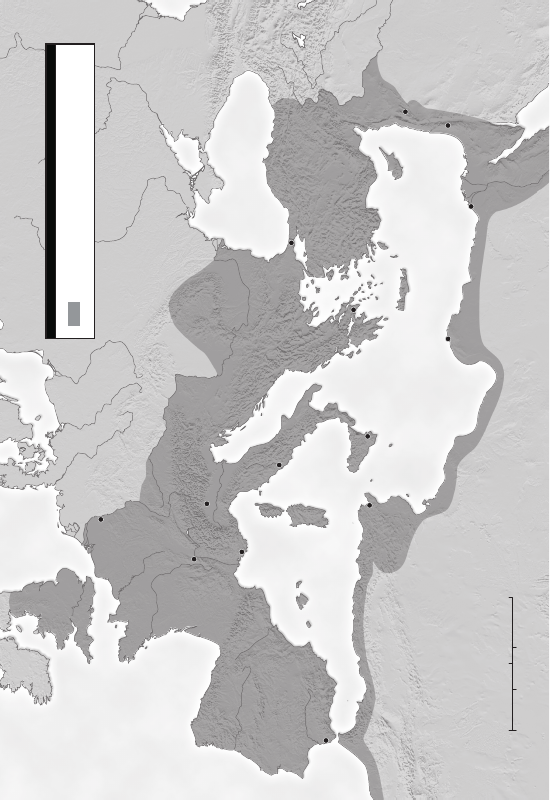

Diaspora Jews

Diaspora comes from a Greek term meaning “scattering.” It is a ref-

erence to the dispersion of the Jews upon their return from exile

in Babylon (587–538 BCE), although the prophet Jeremiah com-

plains about such a development even before the Babylonian exile.

Although many Jews returned to their homeland in Palestine after

the exile, many others established Jewish communities in other

parts of the Mediterranean area. Paul, born and raised in Tarsus of

Cilicia, would have been counted among the scattered Jews. At the

time of Jesus and Paul, in fact, most Jews lived in the diaspora in

such cities as Antioch, Corinth, Rome, Ephesus, and Alexandria. (See

map on p. 31.)

11. For a very good single-volume work that contains all the New Testament

apocryphal writings, including the apocryphal Pauline literature, see J. K. Elliott,

The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an

English Translation based on M. R. James (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993). See also

Richard I. Pervo, The Making of Paul: Constructions of the Apostle in Early Christianity

(Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010).

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 30 2/27/2013 8:38:22 AM

Paul of Tarsus 31

Rome

Cologne

Milan

Lyons

Carthage

Gades

Syracuse

Massilia

Athens

Byzantium

Alexandria

Cyrene

Jerusalem

Damascus

BRITAIN

DACIA

EGYPT

LIBYA

NUMIDIA

CYPRUS

CILICIA

LYCIA

CRETE

MAURETANIA

SPAIN

SICILY

SARDINIA

CORSICA

JUDAEA

MEDIA

ARMENIA

SYRIA

GAUL

BELGIUM

JUTLAND

AUSTRIA

GERMANY

ASIA

MINOR

THRACE

CRIMEA

CAPPADOCIA

MACEDONIA

DALMATIA

MESOPOTAMIA

SAHARA DESERT

ARABIAN

DESERT

North

Sea

Mediterranean Sea

Black Sea

A

d

r

i

a

t

i

c

S

e

a

Red Sea

Baltic

Sea

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

0 500 miles250

0 500 kilometers250

Roman

Empire in

the

1st Century CE

© 2009 ANSELM ACADEMIC

Research in the past few decades has shown that the Judaism

of Paul’s day was quite diverse. Some Jews, for example, were born

and raised in Palestine (Palestinian Jews), like Jesus and many of

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 31 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

32 THE PAULINE LETTERS

his Jewish followers, and spoke Aramaic. Other Jews were born and

raised outside Palestine (diaspora Jews), like Paul and many other

first-century CE Jews, and spoke Greek. Various other Jewish groups

also had a presence in the first-century CE world. A small percent-

age of Palestinian and diaspora Jews belonged to the elite groups of

the Sadducees (a conservative aristocracy), the Pharisees (interpret-

ers of the oral and written Mosaic Law; the group to which Paul

belonged—Phil 3:5; Acts 22:3), and the scribes (trained scholars).

Most Palestinian Jews either lived in the Palestinian countryside and

were simply referred to as the ‘Am ha-‘aretz (in Hebrew, the “people

of the land”) or resided in the cities scattered throughout the Roman

Empire. Some Palestinian Jews were revolutionaries trying to evict

Romans from their Jewish homeland of Palestine (the Zealots and

Sicarii), while others lived in isolated communities anticipating the

Messianic Age (the Essenes). The differing religious and political

views of these Jewish groups affected how they lived their Jewish

faith. For example, different understandings of purity and the calen-

dar was the subject of intense debate among the Jews.

Despite their diversity of beliefs and practices, the various Jewish

groups agreed on four fundamental areas: belief in their covenantal

relationship with a single God (YHWH); conviction in the divine

election of Israel among all the other nations; reverence and adher-

ence to the divinely revealed instructions of the Mosaic Law (the

Torah); and devotion to the Temple in their capital city of Jerusalem.

These defining characteristics separated Jews from the other nations,

and they would be the very issues Paul would integrate into his mes-

sage and missionary outreach to the Gentiles about the crucified and

resurrected Messiah.

In addition to these Jewish influences, Paul was impacted by

the Hellenistic culture that had engulfed the ancient Mediterranean

world for centuries before he was born. Paul’s Jewish religious belief

in a single God (monotheism) was certainly not the norm of the

Greco-Roman world. Nearly all people in the Roman Empire were

polytheistic; that is, their religious observances were not restricted

to a particular god or goddess (deity). Cities within the Roman

Empire had sanctuaries, in which devotion to a deity took place by

those trained for the proper ceremonial activities. Religious practices

associated with the mystery cults of the Roman Empire were also

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 32 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

Paul of Tarsus 33

Artemis, the Goddess of Ephesus

In the city of Ephesus, there was the well-known temple devoted

to Artemis, the goddess of fertility. Artemis was one of the most

widely worshipped female gods in the province of Asia.

Acts 19 relates Paul’s encounter in Ephesus with the silver-

smiths and artisans who made miniature silver shrines of Artemis.

Paul publicly challenged the existence of Artemis or any god “made

by human hands.” Paul’s words caused such chaos and confusion

among the citizenry that a riot broke out in the city.

Paul also faced numerous Greek philosophies (worldviews) that

shaped and defined the Hellenistic culture of his day. Among the more

popular philosophies were Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Cynicism.

Epicureanism stressed the material nature of all things (including the

body and soul as perishable), the importance of inner peace and har-

mony, and the complete disconnect between the deities of the other

world and this world. By comparison, Stoicism emphasized the divine

spark in each person and the practice of virtue as the human ideal. In

addition, it taught that the universe was held together by a controlling

principle called the logos (word) and a vital spirit or soul called pneuma

(spirit). Cynicism espoused that true human freedom would come

from living a simple life, void of possession and material wealth.

Alongside these various worldviews, Paul the Pharisee most

likely embraced the Jewish worldview of apocalypticism. As the Ess-

enes also were, the Pharisees were Jewish apocalypticists who viewed

the world as a duality between good and evil. Some first-century CE

Jews anticipated an imminent end to this age (the eschaton), which

common. Participants in these mystery cults kept secret the prac-

tices of the rites performed to their deity. Meals were often shared

among the members of these mystery cults and their deity, with the

assurance of the deity’s protection and special knowledge for cult

members. Among the most popular mystery cults within the Roman

Empire were those of Dionysius, Mithras, and Isis.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 33 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

34 THE PAULINE LETTERS

would culminate in God’s intervention in the world. God, in control

of human history, would send someone to deliver his people from the

forces of evil on Earth, set up God’s kingdom, raise the dead, and

judge the world. These Jews held an apocalyptic eschatology, but many

Jews at this time had no such imminent eschatological expectation.

Paul and his contemporaries were immersed in a diverse arena

of competing beliefs and philosophies. It was to this world that Paul

would bring his gospel of Jesus Christ.

CORE CONCEPTS

●

One of the main areas of research on Paul for the past two

hundred years has been Paul’s relation to the Judaism of his day.

●

James D. G. Dunn coined the term the new perspective to

describe recent Pauline scholarship that sees Paul more as a

reformer within the Judaism of his day.

●

E. P. Sanders’s concept of covenantal nomism stemmed from

a new perspective in studying Paul within the context of

ancient Judaism.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

●

Source material on Paul is plentiful.

●

Most of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century New Testa-

ment scholarship portrayed the Judaism of Paul’s day in

negative terms.

●

Paul and his letters are best understood within the chronol-

ogy of his life, the evolution of his own theological thinking,

and the historical developments within the first and second

generations of Christians.

●

The seven undisputed letters of Paul provide the primary

source material on Paul.

●

Both Jewish and Hellenistic influences shaped Paul’s life

and worldview.

●

Paul can be understood as a Jewish apocalyptic Pharisee.

Summary: Understanding

and Interpreting Paul

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 34 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

Paul of Tarsus 35

THE LIFE AND LETTERS OF PAUL

The second part of this chapter begins with a chronological account-

ing of Paul’s life, beginning with his birth and formative years, and

then turning to his life as a Pharisee, his encounter with the risen

Christ, and his missionary work as the apostle to the Gentiles. It

then takes a closer look at the letters of Paul, which includes a dis-

cussion of letter writing in the ancient world and Paul’s use of letter

writing in his outreach to the Gentiles. This section concludes with a

discussion of the composition and formation of what is known as the

Pauline Corpus, the body of Paul’s works.

The Life of Paul

Paul’s Birth and Formative Years in Tarsus

Paul’s letters and the Acts of the Apostles say nothing about

when Paul was born and very little about his formative years. The

only clue to the year of Paul’s birth comes from an incidental com-

ment Paul makes in his letter to Philemon, written around 60 CE.

There, Paul refers to himself as an old man (Phlm 9), which would

have made him perhaps fifty years old in the early 60s. This clue

points to the possibility that Paul was born sometime between the

years 5 and 15 of the first century CE. Nothing is written of Paul’s

parents or other relatives, aside from his parents being Jewish (Phil

3:5), but he did apparently have at least one sister (Acts 23:16).

Paul never married (1 Cor 7:7–8), and so it is assumed that he had

no children.

What scholars do know is that Paul claimed to be a descendent

from the tribe of Benjamin (Rom 11:1; Phil 3:5) and, according to

Acts, was born and raised in Tarsus, the capital city of Cilicia in the

southeastern part of the province of Asia Minor (Acts 21:39, 22:3).

Tarsus stood at the crossroads of major commerce and trade routes.

A wealthy, metropolitan Hellenistic city with a large Jewish popula-

tion, Tarsus was known for its Hellenistic school, which trained and

educated the elite in philosophy, rhetoric, and poetry. As an urban

Jew surrounded by Hellenistic culture, Paul was exposed to a mul-

ticultural environment during his formative years and was conver-

sant in the oral and written dialect of Koinē (common Greek)—the

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 35 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

36 THE PAULINE LETTERS

language of his letters and the entire New Testament. According to

Acts, Paul returned occasionally to his hometown after his conver-

sion and during his missionary travels (Acts 9:30, 11:25).

Although Paul never speaks directly of any formal training and

education he may have received, his letters point to the use of both

Greco-Roman rhetorical style and Jewish interpretive practices. For

example, in his letters, Paul employed the literary device of “diatribe,”

common to the Cynic and Stoic philosophers of his day, in which

questions are put forth and then refuted (for instance, Rom 10:5–8).

In addition, similar to the Jewish Pesher or Midrash (interpretation

of Scripture) of his day, Paul applied the Jewish Scriptures to his new

situation of faith in Christ as the Messiah and Son of God (such as

1 Cor 10:1–4).

Paul the Pharisee

Paul refers to himself as a Pharisee (Phil 3:5). In fact, Paul says

he was “a zealot for my ancestral traditions” and had “progressed in

Judaism beyond many of my contemporaries among my race” (Gal

1:14). Pharisees were descendents of the Hasidim, a resistance

Was Paul a Roman Citizen?

Luke writes in the Acts of the Apostles that Paul was a Roman

citizen (Acts 16:37–38, 22:27, 23:27). Yet nowhere in any of Paul’s

undisputed letters does he mention his Roman citizenship. Roman

citizenship could be obtained by means other than birth, such as

adoption into a prominent Roman household or release from slav-

ery. It is entirely plausible that Paul inherited Roman citizenship

from his family ancestry of being freed Jewish slaves.

The tradition that Paul was martyred by being beheaded is

consistent with Luke’s statement of Paul’s Roman citizenship, as

Roman citizens found guilty of capital crimes against the state were

spared torturous deaths. However, there is no reliable historical

basis for this later apocryphal tradition. The tradition of Paul’s mar-

tyrdom by decapitation could be based in part upon Acts, rather

than any certain knowledge of the historical Paul.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 36 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

Paul of Tarsus 37

movement that originated in response to the oppressive rule of

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–163 BCE). Pharisees saw themselves

as the interpreters, and the social enforcers, of the Mosaic Law and

the oral law that evolved from its interpretation. Where Paul received

his Pharisaic training is unknown, although Luke writes that Paul

trained “at the feet of Gamaliel” (Acts 22:3), the well-known and

respected teacher of Jerusalem. Paul himself gives no indication that

he ever formally studied in Jerusalem under Gamaliel. As a Pharisee,

Paul would have viewed the Torah (the written law) and his “ances-

tral traditions” (the oral law) as the center of his religious identity

and life.

Paul’s extremely zealous attitude toward the Mosaic Law most

likely fueled his persecution of the early Christians, as he saw these

Christ-believing Jews as a threat to the other Torah-observant Jews.

Paul likely perceived this band of Jews’ profession of faith in this man

as blasphemy, which certainly provided enough justification to try to

stop the spread of this dangerous message.

Was Paul also Known by the Name

Saul

?

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke sometimes refers to Paul as Saul.

This mostly occurs in Luke’s references to Paul before his encounter

with Christ (Acts 7:58, 8:1–3, 9:1). Twice after he meets the resur-

rected Christ, Luke calls Paul by the name Saul. In Acts 13:9, Luke

uses these names side by side, “But Saul, also known as Paul . . .”

After Acts 13:9, he is always called Paul, except when Saul/Paul

recounts his earlier vision of Jesus (Acts 22:7,13; 26:14).

The name Paul is the Greek equivalent to the Semitic name

Saul. In other words, the name Paul reflects the Greco-Roman cul-

ture in which Paul was raised (the city of Tarsus, Cilicia), and the

name Saul reflects Paul’s Jewish heritage. Paul lived in both the Hel-

lenistic and Jewish world.

Interestingly, Paul never refers to himself as Saul in his letters.

This may simply be an indication of his largely Gentile audience

who would know him only as Paul. It is more likely, however, that

Paul never used the name Saul for himself, reflecting his life as a

Hellenized Jew.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 37 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

38 THE PAULINE LETTERS

12. See Schnelle, 51.

There are only glimpses of Paul the Pharisee during the period

in which he persecuted the early Christians. Scholars can merely

speculate that the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem authorized him to perse-

cute the church. Paul himself says, “I persecuted the church of God

beyond measure and tried to destroy it” (Gal 1:13), and “in zeal I

persecuted the church” (Phil 3:6). In Acts, Luke introduces Paul at

the stoning of Stephen, the first martyr in the Acts of the Apostles

(Acts 7:58). Luke writes that at the stoning of Stephen, the witnesses

“laid down their cloaks at the feet of a young man named Saul,”

an indication that Paul was the one who authorized the stoning.

Luke paints a frightening picture of Paul in his persecution of the

church. He notes that immediately following the stoning of Stephen,

“a severe persecution of the church in Jerusalem” (Acts 8:1) broke

out and that Paul was “trying to destroy the church; entering house

after house and dragging out men and women, he handed them

over for imprisonment” (Acts 8:3). In his persecution of the church,

Luke indicates, Paul was “breathing murderous threats” (Acts 9:1).

Much later in Acts (22:4, 26:9–11), Luke discloses even higher levels

of violence that Paul directed against the church. As Paul himself

reflected upon these actions years after his encounter with the resur-

rected Jesus, he expressed regret: “For I am the least of the apostles,

not fit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of

God” (1Cor 15:9). Luke’s portrayal of Paul, before his conversion,

as one who literally “breathes murder” is, therefore, probably accu-

rate. In one of the later New Testament letters attributed to Paul,

the author in 1 Timothy 1:13 offers an apologetic attempt to present

Paul as ignorant about what he did in persecuting the church.

Paul’s Encounter with the Risen Jesus

Scholars debate about the length of Paul’s persecution of the

early church and the year in which Paul received his call and com-

mission. Dating Jesus’ crucifixion in the year 30 CE, and Paul’s call

and commission in the year 33 CE, is a common position.

12

Paul’s

conviction that God revealed the resurrected Jesus to him reshaped

and reoriented his entire life and worldview. It is difficult to overes-

timate the impact this event made on Paul and his understanding of

himself, Judaism, and the universe.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 38 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

Paul of Tarsus 39

Did Paul Have a “Conversion” Experience?

Interpreters of Paul have traditionally thought that Paul had a “con-

version” experience after meeting the resurrected Christ on the

road to Damascus. By conversion, a change from one religion (in

this case, Pharisaic Judaism) to another (Christianity) is meant. Yet

neither Paul in his letters nor Luke in the Acts of the Apostles uses

the language of conversion in this sense.

Most details of this event come from Luke. Three times Luke

narrates the encounter between the resurrected Jesus and Paul in

the telling of the story of the early church: Acts 9:1–19 (Paul on the

road to Damascus to persecute Christians); Acts 22:3–16 (part of

Paul’s defense speech to the Jews in Jerusalem); and Acts 26:2–18

(part of Paul’s defense speech to King Agrippa). In Acts 22:15, Luke

says that Paul is to be the risen Christ’s “witness” (martus) “before all

to what you have seen and heard.” The idea of “witness” is repeated

in Acts 26:16.

In Galatians 1:11–16, Paul speaks of having a “revelation”

(apokalypsis) of Jesus Christ, and being called by God “to preach”

(euangelizomai) Jesus to the Gentiles. In this revelation and call, it is

doubtful that Paul saw himself converting from one religion (Phari-

saic Judaism) to another (Christianity).

The conversion Paul had was likely an internal one, of heart

and mind, as he sought to reconstruct and redefine his understand-

ing of God, Israel, and himself in light of the crucified and resur-

rected Christ. It should be noted that both call and conversion are

modern terms and that neither is completely adequate for inter-

preting the accounts of Paul and Luke.

Paul speaks briefly to this event in his letters to the Galatians

and the Corinthians, both written about twenty years after the

event and in the specific context of Paul defending his apostolic

status and authority. In 1 Corinthians, Paul writes, “Have I not seen

Jesus our Lord?” (1 Cor 9:1), and “Last of all, as one born abnor-

mally, he appeared to me” (1 Cor 15:8). In Galatians, as part of

his autobiographical sketch, Paul writes that God “was pleased to

reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him to the Gentiles”

(Gal 1:15–16).

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 39 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

40 THE PAULINE LETTERS

That Paul does not discuss this life-changing event in the seven

undisputed letters does not minimize its importance for the forma-

tion of Paul’s theology. After all, in his occasional letters, Paul is

writing to specific circumstances, most of which did not require any

discussion of his original encounter with the risen Jesus.

Paul, Called to Be the Apostle to the Gentiles

The revelation of the resurrected Christ fundamentally changed

Paul’s life. Paul spent the next thirty years fulfilling what he believed

God had called him to do: preach the good news of Jesus Christ to

Gentiles. This revelation and call made Paul’s gospel distinct among

all others who were spreading the “good news” of the death and

Resurrection of Jesus. The following reconstruction of these thirty

years is based upon what can be gleaned from Paul’s letters, cross-

referenced (when possible) with Luke’s account of Paul’s missionary

journeys in the Acts of the Apostles. It begins in 33 CE, the approxi-

mate year Paul experienced the resurrected Christ.

Immediately following his revelation, Paul reports going into

Arabia and returning to Damascus (Gal 1:17). Exactly how long Paul

stayed in Arabia or how far he traveled into Arabia before return-

ing to Damascus is unknown. However “after three years” (about 35

or 36 CE), Paul went to Jerusalem “to confer” with Cephas (Peter)

and stayed with him for fifteen days (Gal 1:18). From there, Paul

traveled in the regions of Syria and Cilicia, presumably on his initial

missionary outreach to the Gentiles of that region (Gal 1:21–24),

joined at some point by Barnabas and Titus. This entailed consider-

able travel by Paul. Jerusalem is about 200 miles south of Damascus.

Paul’s return north to the regions of Syria and Cilicia was closer to

400 miles.

Paul made his second trip to Jerusalem (the so-called Jerusalem

conference) fourteen years later (about 49 CE), after receiving a reve-

lation (Gal 2:2). This time he went with Barnabas (a Judaic Christ-

believer) and Titus (an uncircumcised Gentile Christ-believer), to

present to Peter, James, and John “the gospel” that he “preached to

the Gentiles” in Syria, Cilicia, and elsewhere (Gal 2:1–10). The

Jerusalem conference was likely intended to resolve the growing

tensions between Judaic and Gentile Christians, specifically around

the question of admitting Gentiles as equal members of the church.

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 40 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

Paul of Tarsus 41

Paul’s Autobiography

The closest thing to an autobiography of Paul is found in the undis-

puted letters of Galatians 1:11–24 and Philippians 3:4–11. These

passages, although limited in scope, contain some details on Paul’s

life, in his own words:

●

Born into the race of Israel, the tribe of Benjamin (Phil 3:5)

●

Jewish parents (Phil 3:5)

●

Circumcised on the eighth day (Phil 3:5)

●

A Pharisee, zealous for his ancestral traditions (Gal 1:14; Phil 3:5)

●

Progressed in Judaism beyond many of his peers (Gal 1:14)

●

Blameless before the law (Phil 3:6)

●

Zealously persecuted the church and tried to destroy it

(Gal 1:13; Phil 3:6)

●

Had a revelation of God’s resurrected Son (Gal 1:16)

●

Called to proclaim Jesus to the Gentiles (Gal 1:16)

●

Visited with Peter in Jerusalem three years after his encounter

with the risen Jesus (Gal 1:18)

●

Was initially well known for going from persecutor of the

churches to defender of the faith (Gal 1:22–23)

Peter and Paul apparently reached some kind of an agreement,

shaking “their right hands in partnership,” and concluding that

Paul and Barnabas would continue their missionary work to the

Gentiles, and Peter, James, and John would go “to the circumcised”

(the Jews).

Precisely what was agreed at the Jerusalem meeting is uncer-

tain. For example, a two-pronged mission to Jews (led by Peter) and

Gentiles (led by Paul) does not address what kind of community

the church would form among the many Jews living in the diaspora.

Paul then met Peter in Antioch, where they argued over the issue

of Jews sharing table-fellowship with Gentiles. Paul “opposed” Peter

“to his face because he was clearly wrong” and acting hypocritically

(along with Barnabas) over not dining with Gentiles (Gal 2:11–13).

Paul and Barnabas went separate ways after they had a falling-out

7044_PaulineLetters Pgs.indd 41 2/27/2013 8:38:24 AM

42 THE PAULINE LETTERS

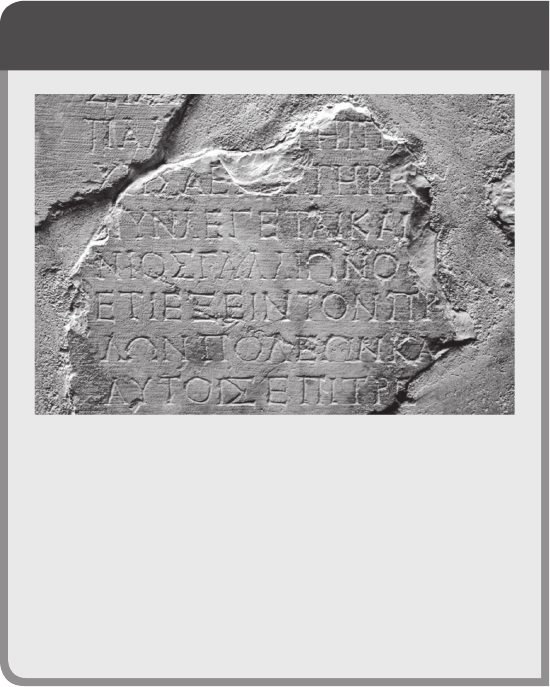

The Gallio Inscription

According to Acts 18:12–16, Paul was brought to trial before Lucius

Gallio, the proconsul of Achaia, sometime during his eighteen-

month stay in the city of Corinth. The “Gallio Inscription,” an inscrip-

tion documenting a letter from emperor Claudius addressed to

Gallio’s successor, offers reliable historical evidence that Gallio was

in Corinth in the summer of 51 CE. This fact provides the only verifi-

able date in the chronology of Paul’s life from which all other dates

are calculated backward or forward.

when Barnabas took the side of the circumcision faction. Accord-

ing to Luke, Paul chose Silas to replace Barnabas (Acts 15:36–41).

Clearly, in Antioch different understandings of the Jerusalem agree-

ment emerged. Does a mission to Gentiles mean accepting Gentiles

as uncircumcised Gentiles who do not eat kosher foods? Do Judaic